Does a winter election spell disaster or deliverance? - Dani Garavelli

December 2000. A muddy field. Falkirk. All of the candidates in the forthcoming Falkirk West by-election have agreed to take part in a football match.

They are decked out in the club’s scarves, both as a show of support for the team and in the hopes of avoiding hypothermia.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Regardless of our political allegiances, the only colour on that field was blue,” says the then Liberal Democrat candidate, Hugh O’Donnell, who lost his deposit. “It was f***ing freezing.”

That bounce match was crazy, but it was non-negotiable, especially for the Lib Dems.

The previous year, at the Hamilton South by-election, the party had been pushed into sixth place by Stephen Mungall, the Hamilton Accies Home, [Jim] Watson Away candidate. Mungall was nominated by fans protesting at the club’s ownership and calling for Accies’ return to the town after it had been forced to move from Douglas Park to Partick Thistle’s Firhill.

Falkirk FC was also campaigning for a new stadium; and the Lib Dems didn’t intend to be humiliated again.

“There was a huge amount of effort on behalf of all the candidates to stop Falkirk FC fans putting up a candidate,” says O’Donnell, who went on to be a list MSP for Central Scotland.

O’Donnell had pounded the streets during the Hamilton by-election, but Falkirk was the first by-election he fought as a candidate. His blooding if you like. Or rather his icing.

“It wasn’t a good winter – and with it being the run-up to Christmas, the High Street was quite congested with the usual charity can rattlers,” he says.

“Shopping centres weren’t keen on you going inside so you were exposed to the elements all the time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I bought a set of long johns and a matching set of waterproof jacket and trousers like you would wear for playing golf. I don’t suppose anyone was able to identify the face of the candidates because we were all wrapped up like nobody’s business. It wasn’t a whole load of fun.”

The turnout on the day – 21 December – was 36 per cent.

There may be a run on long johns this winter. In this age of confusion it is impossible to predict what will happen Brexit-wise.

But Boris Johnson has said he wants a general election on December 12 – just nine days shy of the shortest day of the year. The thought is daunting.

There will be few enough daylight hours in London, but in Orkney and Shetland the sun will rise around 9am and set around 3pm.

The country’s most northerly constituency, it has 34 inhabited islands linked by ferries and planes – all highly susceptible to being grounded by bad weather.

With Christmas approaching, everyone is busy. Schools and community halls are holding nativity plays, concerts and fairs. Most people are harassed; those who aren’t harassed are drunk.

And everyone is craving a break from Brexit. Will political parties be able to galvanise their activists into knocking on doors? And will the activists be able to galvanise voters into making the trip to the polling station?

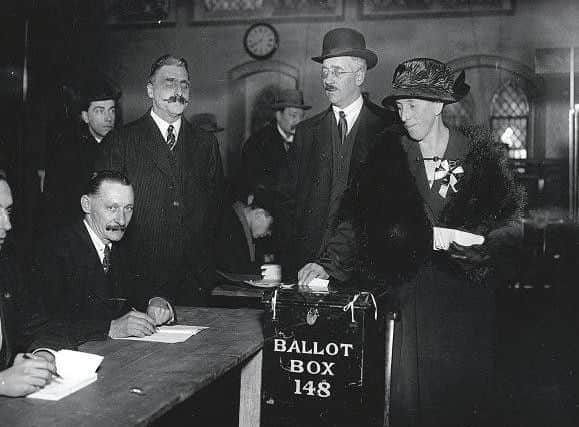

The history of winter elections

Psephologist Professor Sir John Curtice says past experience does not suggest holding general elections in winter has much impact on turnout. It is true that the lowest ever turnout – 56 per cent – was the election held in December 1918, but that was largely because it was held during the flu epidemic and many of the troops had not returned from overseas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the 1923 election – the last general election to be held in December – turnout was 71 per cent, while the election of February 1950 – the first to be covered on TV – holds the record for the highest ever turnout at 83.9 per cent.

The last winter general election, in February 1974, has a good deal in common with this prospective election. It took place at a time of national crisis (caused b y widespread industrial action) and centred on the question: Who Governs Britain? Turnout was a healthy 78.8 per cent.

Unfortunately, the question was not satisfactorily resolved as the vote ended in a hung parliament, a minority Labour government and a further election seven months later.

“If you look at the first seven elections of the 20th century, starting in 1900, five of them took place in winter, two in December,” says Curtice.

“The last winter one – in 1974 – was precipitated by the coal miners’ strike, the three-day week, electricity being turned on and off – all of which is unimaginable now in our digital world – and the turnout went up markedly from the previous election in 1970 [from 72 per cent to 78 per cent].

“So, does it have an impact on turnout in general elections? The answer, from the evidence we have is: not obviously so, although the turnouts in by-elections go down the closer they are to Christmas.

“What has changed is that we now have this standard position where we shut the country down for two weeks – we weren’t doing that in the 1920s. And we have become fragile souls in our centrally-heated, well-lit world.

You might think our forebears in the 20th century didn’t have cars, didn’t have central heating, were relying on gas light in many cases, and somehow or other managed it when supposedly we can’t.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is true. But a December election might legitimately impact on some demographics: old people might be too scared of slipping on icy pavements to leave the house; parents of young families might be too busy shopping and wrapping gifts; those in remote rural locations might be cut off by wind, rain or snow.

Fewer people willing to go door-to-door

But let’s rewind. Because the potential challenges of a December election begin long before polling day, and affect activists, head teachers, polling clerks, ballot counters and returning officers as well as voters.

Labour activist Duncan Hothersall is under no illusions about how easy it will be to persuade activists (particularly women) to knock doors after dark.

“To be honest, the sorts of people who will trudge the streets will trudge the streets in any weather you ask them to. The challenge for parties, especially Labour, is there are fewer and fewer people who are willing to trudge the streets for reasons that are well-known,” he says.

“And there are definitely things that are harder to do in winter. People really don’t like answering the door after dark which means you are restricted to weekends and whoever you can get out in the daytime during the week. In the evenings you have to shift to a phone banking model and a lot of people who are prepared to knock doors are not prepared to phone.

“A lot of volunteers will be working during the week, so it is a bigger challenge to harness their evenings and you are putting a hell of a lot of effort into the weekends when you have got daylight. I imagine you would see people powering through Sundays.”

With only three weeks of formal campaigning, one week of snow and/or gale force winds could be hugely damaging. And that’s just the weather. If the election is held on 14 December, organisers will also have to compete with Christmas parties, with most of the halls for activist and public meetings booked up long ago and few people interested in attending.

“I don’t know how many campaigns would try to do public meetings, but it would be almost impossible. It would be like campaigning in Edinburgh during the festival with no available venues – you would just be stymied,” says Hothersall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor non-party members trying to organise election day, a December election also poses a challenge. Those schools and halls which are traditionally used as polling stations may already have events planned. Returning officers have the power to compel schools and users of other public buildings to make space for polling stations, but this is rarely if ever done.

Boris Johnson may believe “democracy” is more important than any nativity play, but who would be brave enough to tell a P1 parent they had to sacrifice seeing their child play Shepherd Number Six for the greater good of the country?

Facing the cold

Then there is the question of staffing them. Dr Alistair Clark, reader of politics at Newcastle University, has carried out research into the motivations of those who work in polling stations and says even in the run-up to May elections recruitment can be a struggle.

Will the lure of a bit of extra cash at Christmas be enough to offset the prospect of sitting in a drafty hall for 16 solid hours?

“It’s hard enough generally,” Clark says. “Can you imagine doing this in a polling station up on the north coast on a dark and dreich December day? And you have to drive home afterwards.”

Clark says 60 per cent of those who work in polling stations are women. “Around 80 per cent of the people we asked said they wanted to earn some extra money,” he added, “but that wasn’t their only motivation.

Seventy per cent said they wanted to experience the democratic process, with around two thirds saying they felt it was a kind of duty as a citizen. In the last general election, Glasgow had just under 500 polling stations, Aberdeen had around 140 and Dundee had around 150. When you think every polling station has two people at the desk: that’s an awful lot of people,” says Clark.

“And that’s in the cities. Think of trying to organise it in the Highlands or Argyll and Bute where you also have issues of distance and remoteness and all of these sorts of things.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome councils are planning to buy-in temporary street lighting for health and safety reasons. They may also have to make practical provisions for bad weather like hiring gritters and ensuring extra transport for people who find it harder to get out to vote.

Last week, the Association of Electoral Administrators (AEA) warned the late date was causing problems as organisers found their venues of choice had been booked for pre-Christmas events.

AEA deputy chief executive, Laura Lock warned this might lead to the counts being held in smaller venues, which could mean later declarations because staff have less room in which to work.

A former member of the Youth Parliament, Amy Lee Fraioli, 22, counted ballots in South Lanarkshire in the 2015, 2016 and 2017 elections.

She got involved as a means of experiencing and learning about the democratic process and loved the feeling of being in the thick of the action, though, having now become a Labour party activist, she thinks it’s unlikely she will do it again.

“I think they might struggle to get people this time round,” she says.

“The South Lanarkshire centre is in East Kilbride which is quite out there. Those who don’t drive would have to take public transport and it would be dark by the time they arrived. That’s on top of the fact that there will be a lot of Christmas events going on, and people are a bit fed up with politics at the moment.”

One answer to all this might be to encourage more postal votes, but this too will be a complicated logistical exercise. Last time round there were 7.6 million postal voters. This time there are likely to be more.

A disaster in the making

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut voting papers can’t be printed until nominations have closed (14 November for a 12 December election) and there are only so many firms able to do the printing. Those who wish to register for a postal vote would have to do so before 26 November. All this will put extra pressure on the already over-loaded postal service in the run-up to Christmas.

The fact the register of voters is updated every year on 1 December is likely to prove a double-edged sword. On the plus-side it means it will be a more accurate reflection of eligibility which, in turn, means the turn-out figure will be higher.

On the flip-side, polling cards, which have to be sent out weeks in advance, will be distributed on the basis of the old register, which will inevitably lead to some confusion.

When you bring all of these factors together, a 12 December election sounds like a disaster in the making.

Yet Curtice believes, regardless of the weather, the country is likely to approach it with something close to zeal. “People on both sides of the argument care passionately about Brexit,” he says. “We have levels of engagement in this issue that we have not seen in our party politics since the 1960s. I think it would be surprising if turnout doesn’t go up.”

SNP activist Jonathan Mackie is also upbeat. “Certainly it’s more pleasant to canvas when the sun is shining, it’s 27 degrees and children are playing kerby outside their houses, than when you are having to read canvass lists by the light of your mobile phone. There is no getting away from that,” he says.

“But whether or not people are prepared to come out depends more on the way they feel about their party. This is where Labour are going to have a big problem. When you look at their position on Brexit , and what’s happening in Ian Murray’s seat [Unite was pushing for him to be deselected in Edinburgh South] – they might be less likely to go out in the rain, sleet and snow. The other parties are likely to be more motivated.”

As for the voters, Mackie insists their willingness to make the trip to their polling station depends less on the dreariness or otherwise of the weather than the dreariness or otherwise of the campaign.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Like the activists, if voters are motivated to come out, they are motivated to come out, whether it’s peeing with rain or the sun is shining.

“I don’t think the winter and the darkness makes much difference to that,” he says.