Interview: Scots psyche leads to parents passing trauma on to children

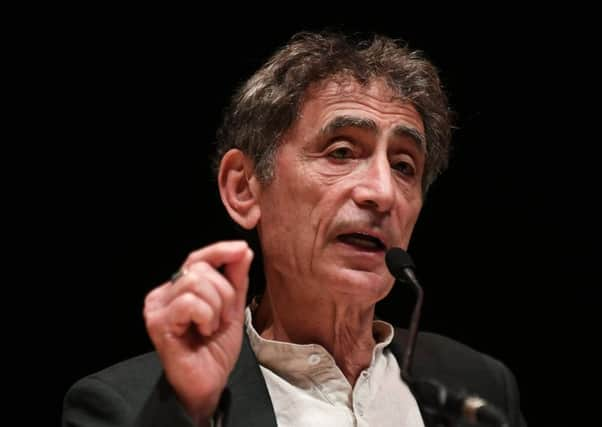

Maté later emigrated to Canada and would go on to forge a career as a doctor, eventually writing about his experiences of working with Vancouver’s drug addicts in his seminal book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts.

He believes the trauma many of us suffer in childhood – sometimes unwittingly caused by loving parents – will ultimately chart the path we take as unhappy adults, whether that means addiction, mental health problems or failing relationships.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was in Scotland this week to speak at a conference on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), the controversial concept currently being unquestioningly adopted by large parts of the public sector.

Born out of research done in 1990s California which linked obesity to childhood trauma, the central tenet of the ACEs agenda is that as the number of negative physical, sexual or emotional experiences increase, so does the incidence of depression, alcoholism, promiscuity and suicide attempts in later life.

The idea has been enthusiastically adopted by the Scottish Government, teachers, psychologists and even Police Scotland, with supporters keen to make Scotland the world’s first “ACE-aware” nation.

Few deny that childhood trauma can have a profound and lasting impact, but some experts believe the ACEs agenda fails to acknowledge socio-economic conditions and has been seized upon as a “magic bullet” at a time when austerity has left support services bereft and unable to cope.

Maté admits the ACEs framework – which allows individuals to “score” themselves based on the number of traumatic events they’ve experienced – is too restrictive.

Despite his early beginnings in Nazi-occupied Budapest, he believes the ACEs model would characterise his childhood as a largely happy one, not one marked by trauma.

“There was no violence in my family; no addiction; no sexual or physical abuse; my parents weren’t jailed; there was no mental illness. So according to the strict ACE criteria, I might not even qualify,” he says.

“These studies, as necessary and as vital as they are, they don’t include everything. They don’t include the terrible stresses infants undergo when their parents are suffering. I don’t recall being an infant, but it’s stamped in my brain, in my physiology and psychology. The ACEs studies can only deal with what can be recalled, and they’re not complete in that sense.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaté says that when you factor in the stress his pregnant mother was experiencing, and the stress he endured as a baby born during wartime, he had “major trauma”.

There is evidence that early trauma and exposure to so-called “toxic stress” can have a devastating impact on a child’s biological development.

According to researchers at Harvard University, in cases of chronic abuse – especially during early, sensitive periods of brain development – the parts of the brain involved in fear, anxiety, and impulsive responses can overproduce neural connections while those regions dedicated to reasoning, planning, and behavioural control go into decline.

But the science also indicates the presence of a loving adult can mitigate against the worst effects, helping reduce elevations of the stress hormone cortisol in toddlers.

“What happens to you in the first three or four years of life has the most profound influence on how you’re going to be for the rest of your life,” Maté says. “Those early experiences are powerfully influential, but they’re not written in stone – they can be reversed.”

While he admits poverty plays an important role in a person’s childhood, Maté is keen to stress that adverse experiences can happen to anyone, even those brought up in otherwise loving homes. “Being middle class has nothing to do with it and loving parents aren’t the issue. I love my kids, but I know how I passed my trauma onto them without meaning to. I was a workaholic doctor because I lacked self-worth and that meant daddy wasn’t around. I didn’t do it deliberately; I love my kids and I would have died for them. I was too driven as a physician.”

Central to Maté’s work is the psychology of addiction.

The number of drug deaths in Scotland this year is expected to reach 1,000, the highest rate of death of anywhere in western Europe.

Maté says that in 12 years of working with a drug addicts in Vancouver, there was not one woman he met who had not been sexually abused as a child. Asked why there should be higher rates of drug deaths here than elsewhere in the UK, he says Scotland is a “historically traumatised country,” damaged over decades, if not centuries, by conflict and de-industrialisation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The more traumatised you were in childhood, the less resilient you will be in the face of those social influences,” he says.

While many experts remain deeply sceptical about ACEs, Maté’s message at the ACEs to Assets conference was heard this week by an audience that included those from education, social work and the police.

Asked if he has one piece of advice for parents, he says: “To take care of yourself because it’s not just what you do, but who you are that affects your children.”