Joyce McMillan: Hold tight for the great step forward

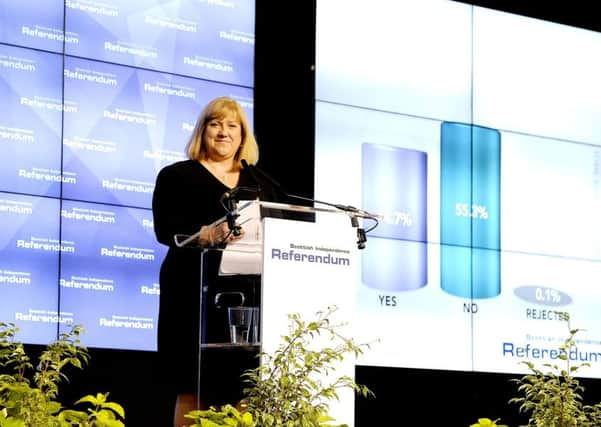

In truth, I can’t remember much about the day we all went to the polls, in the Scottish independence referendum of September 2014. I remember voting “yes”, in a narrow judgment call about whether a Westminster government would ever truly invest in the kind of future Scotland needs. And I remember hoping, nonetheless, that if “yes” won, it would not be by a tiny majority; I thought it would be all but impossible to launch a successful independent nation with half of the people still in mourning for a British identity and citizenship that would have been painfully taken from them, against their will.

Yet if my memories of that day 22 months ago are surprisingly vague, I can still see one truth with surprising clarity; that if the people of Scotland had known, on September 18 2014, that David Cameron’s promised EU referendum would result in a wafer-thin but decisive vote to leave, followed by the raging political omnishambles of the past fortnight, then there really is little doubt that the extra 6 per cent swing needed to reach an independence vote would have been achieved, possibly by a comfortable margin. The vote to remain in the UK was, as David Cameron said at the time, a “vote for stability”, for a relatively predictable future in a big, familiar nation that formed part of the world’s biggest trading bloc, as opposed to the uncertainties of independence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet now, all of those careful calculations have been blown out of the water; for after decades of neglect at the hands of Thatcherite and post-Thatcherite governments, the people of England – or a sufficient majority of English voters – have been seized by a revolutionary mood, and no longer care about the practical consequences of their rage, so long as they can throw a spanner into the national and international works. The stability of the UK, the EU, and to some extent the entire global system has been put at risk; and now Scotland, still undeniably part of the UK, finds itself being towed out into the choppy waters of the Atlantic at the behest of two groups of people – angry English voters reasserting their national sovereignty, and the elite right-wing leaders of the Brexit campaign – neither of whom are likely to have given a second thought to Scotland at any point, during what was, by any measure, a lamentably poor and misleading referendum campaign.

This is not to say that there could be no positive Scottish arguments for Brexit; a million voters here, well over a third of those who turned out, voted to leave, despite strong advice to the contrary from all Scottish political leaders. Yet remarkably, there was a clear majority to remain in every single local authority area, with Edinburgh City emerging as the most pro-EU authority in the UK. And as a consequence, Scotland now faces three possible futures; although none of them is the one we voted for in 2014, which left our three layers of geopolitical identity, Scottish, British and European, all intact.

In the first option – the dream scenario of the SNP and the present Scottish Government – Scotland takes a cold, hard look at the likely character of the UK outside the EU, at a nation without a viable opposition party, locked into what looks like at least a decade of Tory hegemony, and capable – for internal reasons – of appointing a foreigner-baiting buffoon like Boris Johnson as Foreign Secretary, and decides that enough is enough. As Britain prepares for Brexit, this Scotland confidently demands a new independence referendum, votes by a large majority to shake the dust of the UK from its feet, and rejoins the EU, where it is welcomed with open arms.

The only problem with this scenario is that it if it had not been for the extraordinary strength of the social and personal ties that bind Scotland to the rest of the UK, we would surely have taken the independence option long ago; and faced with a straight, painful choice between two identities both of which mean a great deal to Scots, I think it would be a brave First Minister who would bet her entire career, and the future of her party and nation, on the chance of Scotland preferring the EU to the UK.

The second option is to accept that in tough and unstable economic times, independence looks increasingly like a further unnecessary risk in an already risky environment; and therefore to start to reinvest in some new 21st century idea of post-EU Britishness. Practically, this must look like the best option to many, particularly in a business world which knows that Scotland exports four times as much within the UK as to all other EU countries. Culturally and politically, though, it seems an almost impossible task, as the once-unifying Labour Party commits public suicide on the Westminster stage, and UK politics remains obsessively focussed on power-struggles within a Tory party still supported – for all Ruth Davidson’s Westminster grandstanding this week – by barely more than a fifth of Scottish voters.

And then there is the third option: that we neither vote for independence, nor fully accept our place in post-EU Britain, but instead sink into a surly and impoverished acquiescence, in a nation over whose government we now have almost no influence. In this scenario, our recent renaissance of cultural energy and confidence ends in defeat; and huge numbers of Scotland’s best and brightest leave our shores before the Brexit door finally slams at the end of 2018, heading out to Dublin, Amsterdam, Berlin, and beyond.

My view is that the third option is unbearable, and the second, at this stage, almost psychologically impossible. Which leaves only the first: the deep breath, the sober assessment of Scotland’s possible futures, the recognition that our politics and those of England have begun to diverge – for understandable historic reasons – in ways that make our old form of Union unsustainable. Then the vow to hold on tightly to all those we love, across all the borders made and unmade in my lifetime; as we take up our own little shred of sovereignty, and step forward, into new times.