Joyce McMillan: Heroes have gone but their dreams live on

First, the good news, for those of you who were beginning to wonder whether we had all succumbed to some strange perceptual madness over the number of celebrity deaths this year.

According to the head of the BBC’s obituary department, the number of pre-prepared obituaries used this year is 46 per cent higher than in 2015, suggesting that there has indeed been some kind of “grim reaper” effect among the famous. It’s partly demographics, of course; between the 1960s and the 1980s, across Britain and America and beyond, a big “boom” generation of postwar teenagers began to find their voices and identities through the work of a slightly older generation of music-makers, film actors and television stars whose work spread across the globe at a rate and with an intensity no-one could have imagined before the Second World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

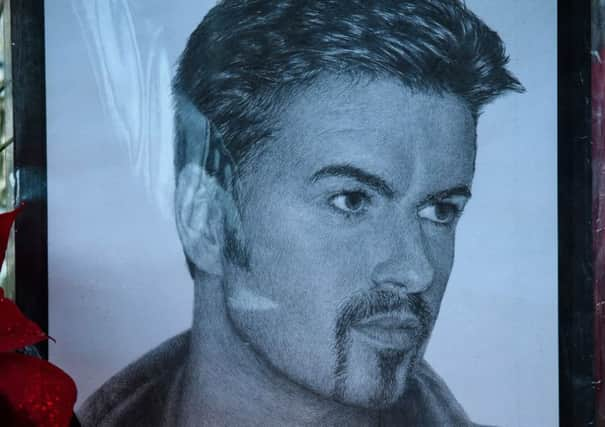

Hide AdNow, those stars who were young between 1960 and 1985 are reaching their threescore years and ten, some dying a little younger, after lives marked by the stress of fame; and so we have the famous litany of this year’s losses, from the great David Bowie at the start of the year, to Leonard Cohen, George Michael and Carrie Fisher at the end, with the added blow of the consequent loss of Fisher’s remarkable mother, Debbie Reynolds. And it seems likely that a higher rate of celebrity loss will become the norm, as the tens of thousands who won fame in the popular culture explosion of the 1960s and 70s begin to file away towards the great post-show party in the sky.

When it comes to the question of how we mourn these stars, though, there still seems to widespread unease. Even among those who do express their sadness online – including, this week, Scotland’s First Minister, a keen teenage George Michael fan – arguments often break out over the tone or extent of the grief expressed. And among those too old to care about most of the celebrities involved, or too busy to pay attention to media coverage of any kind, there is much scepticism about whether these expressions of “grief” for distant celebrities can possibly amount to more than delusional self-indulgence; ever since the outpouring of popular feeling over the death of Diana Princess of Wales, almost 20 years ago, there has been no shortage of voices prepared to denounce the whole business as some kind of hysteria, and to invite people to start mourning instead for those they really knew.

Yet in truth, we all know that human societies do not work like that, and that the personas developed by people of fame – kings and emperors, saints and generals – have always been capable of exerting real and lasting effects on the lives of their fans. There are certainly some deeply disturbing aspects of today’s celebrity culture; a sense of its being used as a kind of opium of the people, as the huge television screens that now dominate many homes threaten to drown out real, substantive forms of conviviality, from family conversations to a night in the pub. Disengagement from politics at all levels, alienation from real community life, a tendency to “identify upward” with the rich and famous rather than to form bonds of solidarity with those in the same position as yourself – all these may well be symptoms of a powerful screen-driven celebrity culture in full cry. And there’s no doubt that celebrity culture can help to normalise and promote individuals like Donald Trump, who surely would not be President-elect today if it had not been for his nationwide television fame as chair of the American version of The Apprentice.

It seems to me, though, that the dominant tone of our celebrity culture – ugly though it can be – is not one of proto-fascist control, but of something more complex. In the first place, mourning for a star like David Bowie or George Michael is clearly a place where many people who have grown up in a mass-media world can find common ground with others; this is a huge, technology-driven leap forward for what Goethe once called “elective affinities”, the kind of enlightenment freedom which genuinely allows us to choose our friends and associates, and the cultural family in which we feel most at home.

Then secondly, most of the stars being mourned are not themselves reactionaries, but people with a genuine feeling for human rights and freedom. George Michael was an elegant and brilliant fighter for the full acceptance of gay sexuality, a massive charitable donor, and an opponent of Margaret Thatcher and all her works. Carrie Fisher was a true feminist, a great satirical writer, and a ground-breaking activist for those suffering from mental health issues. Leonard Cohen was a mighty poet of Sixties dissent, Bowie a radical, questioning, endlessly self-reinventing artist throughout his life. “We don’t cry because we knew them, but because they helped us to know ourselves,” said one Bowie mourner; and this is a strain of genuine grief, loss and appreciation that is not to be dismissed, even if it is mediated in ways that barely existed 20 years ago.

The great conundrum of our time, of course, is how to make an effective political or social force of this intense virtual shared experience, which as yet seems practically powerless against those ruthless manipulators who use media fame alongside more traditional forms of power. If there is one thing to be learned from this frightening year in politics, though, it’s that media-driven popular feeling, built up over long decades, can suddenly transform into an irresistible force for change, under the right conditions. “Our heroes are dead, and our enemies are in power,” said one internet image circulating this week, with an image of a woebegone-looking Charlie Brown. If heroes like Bowie, George Michael and Carrie Fisher are dead, though, the generation who mourn them live on, now using their shared sense of loss to forge their own collective identity; and my hope is that the force will be with them, if and when they finally start organising to reclaim the world for the tolerance, equality, and true creative freedom of which those artists dreamed, to the end.