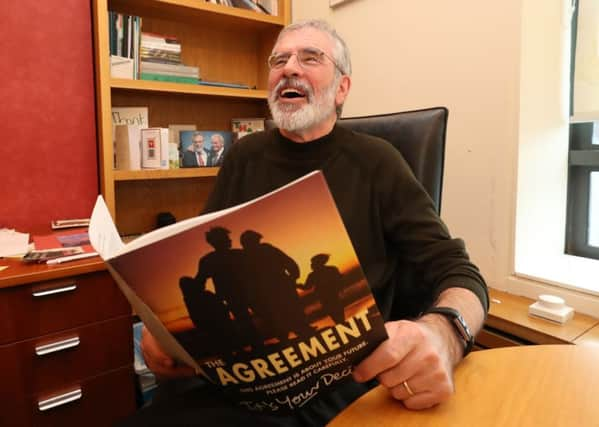

Gerry Adams: Good Friday Agreement can still lead to brighter future

As March 1998 came to an end, George Mitchell set the two weeks prior to 10 April for the final round of talks. Sinn Féin had been consistently calling for an intense, concentrated negotiation with a fixed time-frame to create a dynamic to the talks. And here it was. It was an exhausting two weeks. It was made all the more difficult by the Ulster Unionist Party who wouldn’t talk directly to Sinn Féin. They made the mistake of allowing the British Government to speak for them. Not a good move. For unionism.

At the heart of the Sinn Féin approach was a core group of leadership figures. Our negotiating team, and the small number of drafters – those who had the job of parsing documents and writing our draft responses – and the PR people, would come together around the core group to review the work to date. We had a position paper that set out our goals, and this was the template for all our discussions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGoing into that fortnight, Sinn Féin knew that policing and criminal justice were not problems that could be resolved in this negotiation. We wanted the end to the RUC. This was unlikely to be agreed at this stage. A mechanism was needed, which would have its own dynamic to push ahead on these matters. Commissions were the obvious answer and we plumped for two commissions rather than one.

We also worked closely with the Irish government though we weren’t always satisfied with their position on some issues. For example, the number of cross-border bodies. I also met John Hume on an ongoing basis.

Papers were produced on specific issues and circulated to all of the parties. Changes were made. Words were redrafted. Some were accepted. Others were not. And as the days passed slow progress began to be made on the wide range of issues involved in the talks.

At the same time, the Irish and British governments were negotiating with each other, especially on all-Ireland bodies in the Strand 2 negotiation.

In early conversations with the British Prime Minister, I remember telling him that, for an Assembly to work, the equality and human rights agenda and safeguards against a repeat of past abuses were essential. I repeated this in conversations with the Taoiseach. Sinn Féin stressed the importance of the agreement having a firm legislative basis. This would minimise the possibility of unionists within the Assembly making changes to what was agreed.

It was also obvious that the UUP was playing a tactical game designed to minimise the potential of the talks, and to force nationalists and republicans to accept less than we were entitled to. The DUP famously weren’t there. That was their choice. That also was not a good move. For unionism.

The six-county state was entirely unionist in its ethos and agencies. This not only meant that there had to be a huge amount of change at every level to bring about a level playing field. As John Hume and I had made clear some years before, an internal – that is a six-county – solution was not viable. The Unionists also appeared to lack any real notion of the depth of republican or nationalist alienation or the determination on our part to change all this. So they put a lot of wasted effort into trying to wear us down.

This was one of the products of decades of refusing to deal with genuine grievances or to engage in dialogue with us, or people like us.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLooking back on that time and reviewing the intervening 20 years, and especially the events of the last 16 months, since the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal emerged, it is obvious that this refusal by unionist leaders to try to understand republicans and nationalists remains a serious problem.

And therein lies one of the dangers confronting the Good Friday Agreement; a danger which is at the heart of the current crisis.

The big challenge therefore, for Sinn Féin in the time ahead, especially in the context of Brexit, is to persuade unionism that republicans have no intention of treating them as anything less than equals.

We believe in the Good Friday Agreement and in the institutions. We are committed to their restoration, but it can only be on the basis of respect and an appreciation that our future must be a shared future.

It’s time to draw a second breath and re-engage with each other to build a future in which no one will feel alienated or second class. I believe that better future is still possible.

Gerry Adams, who was leader of Sinn Féin from 1983 to February this year, is a member of the Irish parliament for Louth