Paris Gourtsoyannis: The key questions around immigration and Brexit

Not before the autumn – and perhaps even longer.

Freedom to develop a new immigration policy free from the requirement for free movement of people within the EU was one the key promises made by Brexiteers during the referendum, and work on what that might look like began almost a year ago. In July 2017, the Migration Advisory Committee was tasked with examining the impact of Brexit on immigration, and assessing how a new policy should work.

Having commissioned that work, it never made sense for the government to prejudge it, so promises of an immigration white paper before Christmas, and then by spring, were perhaps unsurprisingly not kept. The MAC report is due in September, but reports suggest the relatively new Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, might want more time to consider its finding before rushing out the government’s response.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Brexit talks in Brussels drag on, with the UK’s negotiating position undermined by the deadlock over the Irish border, there is also the growing risk that the EU could put long-term UK participation in freedom of movement back on the table as one of its demands. If that’s the situation come the autumn, then UK ministers might keep their cards close to their chests for what could become a drawn-out negotiation over migration policy that runs into the post-Brexit transition period.

Will the government hang on to its 100,000 target for net migration?

The government’s flagship immigration policy – to reduce net migration to the “tens of thousands” – has never been under as much pressure as it is now.

Senior Conservative figures like Ruth Davidson are openly questioning it, and the new Home Secretary has refused to give it his whole-hearted support. With Brexit on the way, many cheerleaders for low immigration are less concerned about the figures than they are about making sure free movement comes to an end, so tweaks removing students from the overall figure aren’t out of the question. However, it seems unlikely that the target will be ditched until one of its key architects is also out of office. That’s the Prime Minister.

What does the UK need from its new immigration system?

Put simply, it needs to replace the EU workers that aren’t going to be available anymore. Net migration from the EU has plummeted since 2016, dipping below 100,000 earlier this year, its lowest level for five years.

One in ten workers in some sectors are EU nationals, while in the public sector, the NHS alone employs 55,000 EU nationals including one in ten doctors.

UK employers have become more reliant on EU labour over time; the Nursing and Midwifery Council reported that a third of its new entrants were from the EU.

One sector feeling the labour squeeze already is agriculture, which will need 95,000 seasonal workers by 2021, according to the National Farmers Union – almost all will be foreign. Food producers will know how understaffed they’ve been this season by the end of the year, and how much they may have to cut production in future. The seasonal agricultural workers’ scheme was scrapped when the EU expanded; now farmers are desperate for Javid to announce a replacement in the coming months to ensure crops don’t rot in the fields.

Who will a new immigration system benefit?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPolitically, the government is under pressure to end the preferential treatment for EU nationals and equalise the requirements with non-EU migrants.

The problem is that non-EU migration has been tailored for more skilled labour; imposing the current £30,000 non-EU salary requirement for entry would rule out half the UK’s physiotherapists, midwives, farmers, mechanics and plumbers.

Overall, the Commons exiting the EU committee reports that three quarters of EU nationals working in the UK today would not qualify for entry if they had to meet conditions applied to non-EU migrants.

Businesses seeking to sponsor a non-EU national have to wade through thousands of pages of official guidance, making overseas recruitment impossible for all but the biggest companies.

In the long term, countries whose nationals currently face tough entry requirements such as India may demand preferential treatment in exchange for trade negotiations.

Is the government ready for a new immigration system?

Of all the Whitehall departments preparing for Brexit, the Home Office may face the biggest job. It is already adding 1,000 extra border force officers and will spend £450m over two years getting ready for Brexit – but will it be enough?

The Institute for Government has estimated that 5,000 additional civil servants may be needed just to process the residency applications of the three million EU nationals already in the UK.

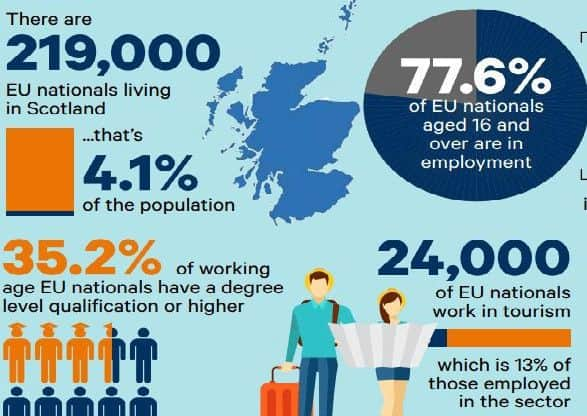

Will Scotland be able to set its immigration policy to meet its particular needs?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a word, no. The UK government has remained implacably opposed to the idea of devolving immigration powers throughout the Brexit process, and the souring of the relationship between Edinburgh and London makes it even less likely now than when the issue was first raised last year.

While there is debate about whether it would be practical or desirable, many experts agree that a regional migration system that allowed workers into parts of the UK to work in specific sectors is at least possible.

For instance, last year the Oxford Migration Observatory said that, while a regional system of migration based on the current tier-two skilled worker visa programme would be “complex”, it dismissed the main argument against it – that areas of the UK with a more liberal policy would become “back doors” into other parts of the country.

The Commons Scottish affairs committee is about to release its report following a six-month examination of devolved immigration, and are widely expected to endorse some form of Scottish work permit.

The Scottish Government points to devolved immigration systems in Australia and Canada and says a similar scheme is essential if Scotland is to combat its low population growth and the inevitable downturn in immigration from the EU after Brexit.

Despite the firm “no” from Whitehall, don’t expect the demands to ease up.