Euan McColm: Left-wingers slowly come to terms with realities of nationalism

There may appear to be irreconcilable differences between socialism and nationalism but these are easily squared by radical lefties, greens and other members of the wider Yes movement who have happily lined up behind the SNP and – at times – treated First Minister Nicola Sturgeon as if she were an anti-establishment firebrand rather than the rather cautious, centrist politician her policies tell us she actually is.

The pro-Yes left winger’s socialism is a curious kind which urges working class solidarity all the way to the border with England but no further. Anyone who questions the logic is a “red Tory” who can comfortably be dismissed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStriking, too, is the assumption of left-wing Yes campaigners that a independent Scotland would be theirs to shape. Members of fringe parties such as RISE (which, so far, hasn’t) have failed to attract any significant electoral support yet they seem to believe that a vote to end the union with England would create a clamour among the people for a radical politics in which they have previously shown little interest.

These would-be nation builders, riding on the coat tails of a self-described nationalist party, get quite irate if one dares suggest they, too, are nationalists. We’re not nationalists, they say, we just want to build a new, fairer nation, without the pernicious influence of Westminster. Which is the sort of thing nationalists say.

But the bonhomie that has existed between the SNP and the Scottish left over recent years may be coming to an end as a series of campaigners speak up in criticism of the recently published report by the Growth Commission on how independence might be achieved.

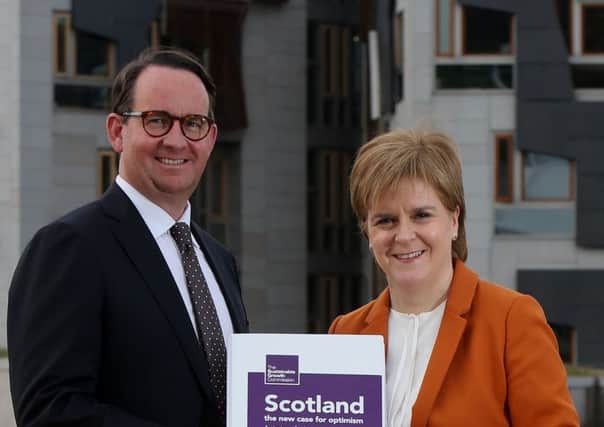

The commission, chaired by Andrew Wilson, unveiled its report a little over a week ago to much praise from both senior SNP figures, including Sturgeon, and (some of) those who remain sceptical about independence. Not only did the commission present a more realistic (if still hypothesised) view of the early years of independence than that outlined in the 2014 white paper, it avoided making the sort of claims of instant Utopia which so seriously undermined the campaign in 2014.

For the radical left, this was a betrayal. Jonathon Shafi, co-founder of the Radical Independence Campaign (which can marshall considerable numbers of those willing to put in the hours on behalf of the cause), said this new vision would be a hard sell on the doorsteps because it would create greater austerity, while Robin McAlpine of the Common Weal called for a swift end to “this Growth Commission madness”.

The writer Darren McGarvey – whose book Poverty Safari is shortlisted for this year’s Orwell Prize for political writing – perhaps best summed up the instinctive response of the left to the commission’s recommendations when he wrote in The Scotsman that the report was “demoralisingly timid”.

Those of the left in Scotland have questions now to ask themselves. Members of the RIC, Common Weal and other groups which have lined up beside the SNP would surely concede that, in any future referendum campaign, the party would once again take the dominant role. Would they simply shut up and follow the nationalists’ cautious line or would they campaign on a completely different prospectus and, in doing so, fatally undermine the Yes campaign with a split which would rightly be regarded as a gift by unionists?

Or maybe they can fight now to change the First Minister’s mind on the Growth Commission report. They would lose this fight, of course, and create another fissure in the Yes movement but, well, principles and all that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerhaps some may return to the fundamental question of whether nationalism and socialism are compatible.

We know from experience of life under both a Conservative government at Westminster and an SNP one at Holyrood that when belts require to be tightened, it is the poorest who are squeezed hardest. Nationalist MSPs might rail against Tory austerity but the double standard rather sticks in the craw. SNP politicians have taken decisions in recent years to provide lavish benefits – council tax freezes, free prescriptions, free university tuition – which disproportionately assist the wealthy while turning a blind eye to the devastating impact on the poorest of cuts to local government budgets.

If the left-wing-nationalist view is that, indeed, the early days of a new nation would require a degree of financial hardship, who do they think would be required to bear it?

Would a new constitutional settlement bring about a profound change in the psyches of Scots? Would, for example, the majority which currently supports welfare reform suddenly evaporate? Would the SNP, which has built its electoral success by targeting middle-class voters (who are most likely to turn out on polling day), suddenly turn on them and take back all that it has given?

There is an indefensibly naive view that, yes, a vote for independence would create a sense of national unity and purpose and that prosperity would spring from it. We know from the results of referendums on independence and Brexit that this is not how things work.

More likely is that the early days of a new nation would provide a breeding ground for harsher policies. We Scots may tell ourselves that we’re peculiarly compassionate but when cuts come, it will be those who get “something for nothing” who take the pain. This is as it has always been. A glib “but we would do things differently” in Scotland doesn’t even begin to credibly address the inconsistencies between socialist fantasy and nationalist reality.

Sturgeon is trying to recalibrate the nationalist campaign, to inject realism into a debate that has lost its way. If campaigners from the left can’t get behind her on the Growth Commission recommendations, perhaps it’s time for them to ask themselves whether independence really is the route to the new society of which they dream.