Euan McColm: Fifty shades of spin beg another question

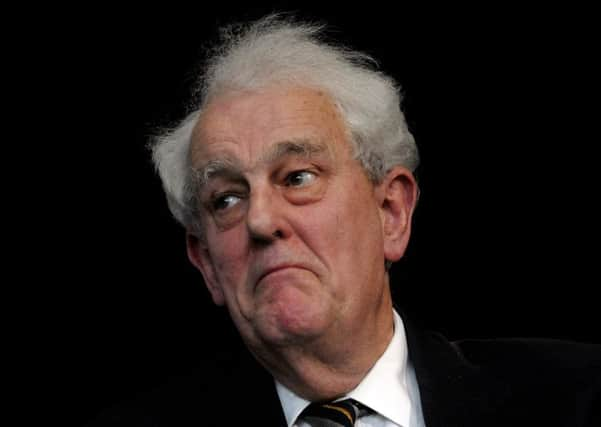

He was, I’d venture, wrong about many things. His refusal ever to countenance support for military action, for example, meant he’d have preferred the UK not to intervene in the Kosovo War, during which campaigns of ethnic cleansing and the summary execution of civilians demonstrated the very worst of humanity. His claim that former prime minister Tony Blair was unduly influenced by “a cabal of Jewish advisers” is simply indefensible.

But Dalyell, for his flaws, was remarkably prescient when it came to the subject of the constitution. Forty years ago, he warned that devolution would weaken the United Kingdom. In what was dubbed the West Lothian Question (after his then constituency), he asked fellow MPs how long they thought English voters and politicians might tolerate members from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland exercising an important – “and probably often decisive” – effect on English politics while they themselves had no say in the same matters in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile campaigners then preparing for the 1979 devolution referendum – which ended in defeat for those in favour of a separate Scottish Parliament – believed a new constitutional settlement would rebalance power, creating a fairer UK, Dalyell felt that such a move would create intolerable tensions and weaken the Union.

It was to be more than 30 years before Dalyell was proved correct. The establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999 may have been designed by Labour politicians to “shoot the nationalist fox” but, of course, it has led us to a position today where the UK looks more fragile than at any point in its 300 year history.

The SNP, for many years, maintained a policy of not voting on matters that, ostensibly, affected only England and Wales. Scottish Nationalists’ answer to the West Lothian Question was to take a position of ostentatious reasonableness.

Now, the SNP does vote on matters that appear only to impact on England. The logic behind this – and, as logic goes, it’s pretty darned sound – is that spending south of the border has a knock-on effect for Scotland in dictating the amount that is released to the Scottish Parliament in the annual block grant. Why shouldn’t MPs from Scotland vote on public spending in England when that has a direct link to how much will be available to spend in their own constituencies?

In the aftermath of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, former Prime Minister David Cameron’s pledge of a new constitutional settlement that would mean English votes for English laws – or EVEL – was further recognition that Dalyell’s warning about devolution was sound. Having created new parliaments in all parts of the UK, Westminster had heightened old tensions.

Those tensions are now close to breaking point.

The SNP is engaged in an increasingly shrill campaign of arguing that an imbalanced UK means Scottish independence is both essential and inevitable. The result of the EU referendum lies at the heart of this argument. Scotland is to be “dragged out” of Europe against its will and only the creation of a new independent state can protect us from this fate.

But while the SNP appears to be reaping the rewards of constitutional chaos predicted by Dalyell, it is some way from achieving its objective. What’s more, the SNP looks to the sceptic as if it has lost its grip on a debate that it has dominated for a decade.

Last week, on the eve of the UK government’s publication of a bill on Article 50 – the mechanism by which departure from the EU will be triggered – the SNP announced that it would be lodging 50 amendments to the proposal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was a gimmicky move rather than the action of a party serious about the debate ahead: it’s called Article 50 so we’ll have 50 amendments – geddit?

At that point, the SNP had no idea what precisely they would be seeking to amend. The pledge of 50 amendments might have been meant to make the nationalists look forensic but it left them looking spin-heavy.

The first few amendments might well look reasonable and substantial but one wonders what the SNP will have to come up with to reach its promised target. Will their requests become increasingly obscure? Ever more outlandish?

Call me a stick-in-the-mud, if you will, but I think it incumbent on politicians seeking to amend legislation to have seen and digested it before announcing the ways in which it might be changed. The 50 amendment promise betrayed an intention to oppose for opposition’s sake, to make political hay regardless of the substance of what was to be placed before MPs.

It remains firmly the case that, despite SNP spin that the result of last June’s EU referendum would drive Scots towards pro-independence, the break up of the UK remains the desire of only a minority of Scots. No amount of claims by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon that independence is more likely now appear to have made this so.

The First Minister has set her party on a track leading towards a second referendum on Scottish independence and she’s frantically shovelling in the fuel of grievance in the hope of building momentum. So far, she is not making the progress she hopes for.

Perhaps it’s time, then, for a new question to replace the West Lothian one. Let’s name it after the First Minister’s constituency.

The Glasgow Southside Question is this: Could the SNP survive a second referendum defeat?

Nicola Sturgeon may not like the answer.