Euan McColm: Class act needs some good advice on education

My thwocking great ego requires regular stroking and if that means allowing the notion that I hold sway over the most powerful politician in the country to flourish then so be it.

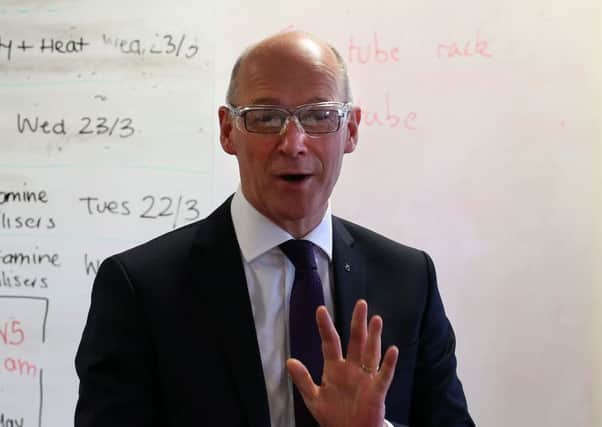

When Nicola Sturgeon completed her reshuffle on Tuesday, I fully indulged my pitiful little fantasy. The First Minister’s decision to shift her deputy, John Swinney, from the Finance brief to Education was – if I chose to ignore the lack of evidence – clear proof that, when it comes to the important matters of the day, she turns first to McColm.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLast November, writing in this here newspaper, I suggested that, if Sturgeon was truly sincere in her commitment to improving educational standards in Scotland, she should sack Angela Constance and put Swinney in charge.

What explanation for this decision could there be, other than that the First Minister believes me to be one of the great thinkers of our time?

One, I suppose, might be that I’m not actually a strategic genius, after all, and instead possess the less extraordinary skill of being able to see the obvious; Swinney’s promotion – and, given the importance the FM has placed on education, this is a real promotion – was the only logical step she could have taken.

I count myself among Swinney’s many admirers. He is, I think, by far the most impressive parliamentarian now sitting in Holyrood. He is a fierce and focused debater, a shrewd tactician and a decent, affable man. Indeed, his personal qualities were absolutely crucial to the success of the SNP’s minority government between 2007-11. Opposition politicians held almost as low an opinion of then First Minister Alex Salmond as some members of the SNP group did, but they could deal with Swinney. They trusted him. Whether this was always wise is another matter (oddly, Swinney’s ruthlessness frequently goes unnoticed by opponents) but the fact is that he was able to bring opposition members on board when their instincts told them to have nothing to do with the nationalists.

But Swinney’s intellect, political nous, and warm relationships with opponents do not, in themselves, add up to a guarantee that he will succeed in his new task. The problems that exist in Scotland’s education system run deep through schools and beyond, into colleges and universities.

Since it is now accepted by the First Minister that I am an expert on this matter, let me point the new Education Secretary towards some matters in need of attention.

The Curriculum for Excellence was introduced to transform the way schoolchildren are taught. Its aims are laudable enough; in theory, children are given a broader education which equips them for adult life rather than simply learning to pass exams. But there are a number of problems with CfE.

It is already well documented that many teachers feel CfE was introduced without proper preparation and that they were not given the resources required to teach what was expected of them. Another problem that’s becoming increasingly clear is that CfE, with all its feel-good, everyone’s-a-winner intentions, sits uncomfortably with the reality that exams still have to be passed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne senior teacher suggests to me that the problem with CfE is that its structure is fundamentally flawed. It takes as the starting point for its design the primary school years when, perhaps, it should work backwards from the exams pupils will be expected to sit in their teens. For CfE to work effectively, those teaching it should have a clearer vision of how pupils will end up in a position to sit National, Higher, and Advanced Higher exams in their fourth, fifth, and sixth years at secondary.

Add to this lack of focus on how CfE might carry children through to exam success the pressure on teachers to achieve targets, and we see – in some schools – the troubling scenario where pupils who might have been expected to sit their Nationals in fourth year are being encouraged to wait a year in the hope of a better success rate. This means Highers – if they are taken at all – become the focus of the sixth and final year, and Advanced Highers, exams which have some parity with English A levels, are no longer an option.

Swinney would be aided in his task if there was proper data to identify the problems that exist. We know that numeracy and literacy rates have been falling (though this year’s statistics won’t be published until 31 May, rather than in April as before – only a cynic would suggest this change of schedule was introduced to avoid any tricky questions during the Holyrood election campaign) but we could get a better picture of where Scottish education stands if Swinney would overturn a past SNP decision to pull Scotland out of international comparators.

And, along with fixing the Curriculum for Excellence, Swinney must look at further and higher education. Free tuition fees are so totemic to the SNP that former First Minister Alex Salmond had his pledge to keep them painted on a rock which Edinburgh’s compliant Heriot-Watt University now displays.

But while free fees might be a vote-winner among the middle classes, the cost of the policy means more than 130,000 college places have been cut. Furthermore, an upper limit on the number of free places available means some Scottish students miss out on university places which are offered to English students who have to pay.

It’s a deceitful policy that doesn’t widen access to higher education. Rather, it saves well-off parents a few quid.

It is, I suppose, too much to hope for that Swinney might change the Scottish Government’s policy in this area but, if he is truly serious about creating the world-class education system on which the First Minister wishes her government to be judged, he should think long and hard before dismissing the idea out of hand.

John Swinney’s appointment as Education Secretary is very good news. But the challenges he faces are huge and his success is not a foregone conclusion.