Election explained: Do TV debates between party leaders really matter?

Leaders' debates have a relatively short history when it comes to UK elections. The first high-profile example was in 2010 when then prime minister Gordon Brown squared up to David Cameron, the fresh-faced leader of the opposition, and Nick Clegg of the Lib Dems.

Polls ahead of the first debate suggested Cameron and the Conservatives were on course to fall short of an overall majority in the Commons and would require the support of another party to form a government. And that's exactly what happened after election day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany people will recall the big talking point of that first debate in 2010 was how many times both Brown and Cameron claimed to back Clegg's interventions. "I agree with Nick" became a short-lived political catchphrase. It was almost as if both men knew they may have to rely upon Lib Dem support in the future.

Afterwards, newspaper columnists were quick to file breathless opinion pieces on how the TV debates had suddenly catapulted the Lib Dems into the political mainstream.

In the end, the Liberals actually lost five seats at the 2010 poll, although their vote share inched up on the previous election by a single percentage point. So much for the leaders' debates bounce, right?

Conflict = drama

But what did change following the first debates in 2010 was how the media - particularly broadcasters - were able to frame the crucial weeks leading up to the poll.

Think of how general elections usually appear on TV news bulletins. There's lots of footage of leaders out and about in factories, schools, or provincial community centres, surrounded by legions of party activists. These are carefully choreographed events with little chance of spontaneity.

The candidates are generally allowed to make the same points in speeches with no one - bar the odd heckler - able to challenge them.

Conflict - as any wannabe director knows - is the basis of all drama. The prospect of conflict is what makes leaders' debates so appealing to broadcasters. They fervently hope that - with the glare of the cameras on them, and millions watching at home - one of the participants will lose their cool and utter something unguarded, an unscripted insight into what they really plan to do in power.

As anyone who has watched more than one leaders' debate will know, this is rarely the case.

A two party state

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPresidential elections in the US are, with very rare exceptions, a two-horse race between the Republican and Democratic parties. Handily, a straight head-to-head contest is the ideal format for a leaders' debate. The first televised example was when Richard Nixon faced off with John F. Kennedy in 1960. They have been a staple of American news networks' electoral coverage ever since.

But British broadcasters don't have the luxury of a two-party system. At a UK-level, politics may still be dominated by the Conservatives and Labour, but no one can ignore the potential king-maker role played by the Lib Dems. Then there's the various nationalist parties of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland - all of which return MPs, and all of which could potentially play a role in deciding who enters Downing Street.

The problem for broadcasters is, the more participants you have in a debate, the more they are likely to drown each other out. Viewers prefer a straight head-to-head battle, which is why they have become such an event in US presidential contests.

No UK broadcaster has yet found a perfect model that both appeals to viewers and satisfies the various parties standing for election. ITV has opted for a contest between Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn - to the fury of both the Lib Dems and the SNP.

Party preparation

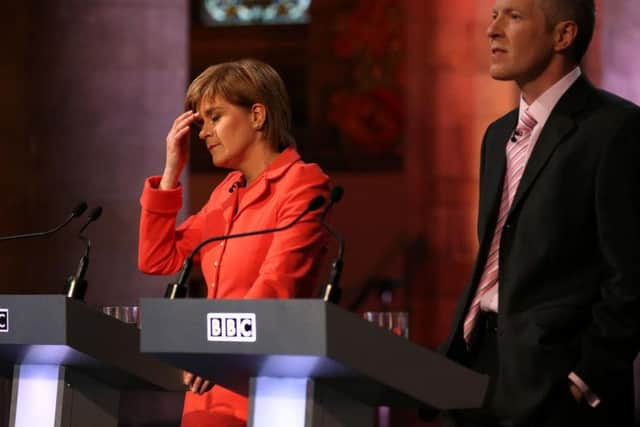

The determination of Jo Swinson and Nicola Sturgeon to have their parties included on UK-wide debates shows how important they view them.

Former Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale today shared a further insight into just how much preparation goes on behind the scenes.

"I’ve spent hours, days even behind the scenes advising politicians on TV debate prep," she wrote. "I advised Alistair Darling in the IndyRef, Jim Murphy in 2015 and even role-played Nicola Sturgeon for Ed Miliband. I took part in a few myself too

"Make no mistake - leaders, or at least their teams will take these occasions really seriously. Working on policy detail, building the political argument on top of that before refining a few soundbites.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"Then you do the same from your opponents perspective, drafting rebuttal for lines you know are coming your way. Strategy is important too - especially in larger debates like the 2015 - six way. Who is the target? Who do you ignore, who is coming for you?

"In a two-way clash like tonight each side will be thinking about moments of clash - what’s the fight they want to be on the 10 o’clock news? The issue they are instinctively comfortable with is not necessarily the one that matters to swing voters.

"Look out for the moment which is for the viewers at home. A policy or a moment of empathy delivered down the barrel of the lens. Look out too for how the leaders try to address any presentational weakness the polls tell them they have.

"In May 2017, there was a suggestion neither Theresa May or a Jeremy Corbyn would take part in the debates. ERS research said that 56% of people thought debates were key to helping them decide who to vote for."