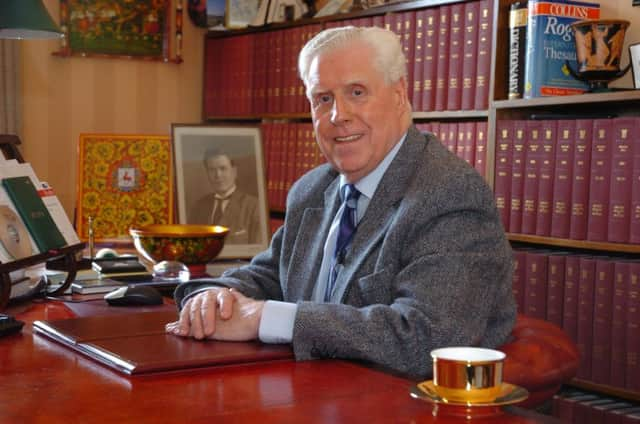

Brian Wilson: A salute to Lord McCluskey

Month after month, evidence was heard in the unlikely setting of the Balmacara Hotel lounge. Apart from reporting the issue at stake, a privilege offered by this spectacle was to witness the greatest legal minds of their generation at work – John McCluskey, James Mackay, Donald Ross, James Clyde – all before they had Lordly handles attached to their jugs.

Maybe it was because of where my sympathies lay but, even in that company, John stood out, his legal incisiveness adorned by elegance of language, capacity for humour and a gentle air of great humanity. These impressions were never contradicted in our encounters thereafter; if I had the misfortune to appear before a High Court judge, I wanted it to be Lord McCluskey.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe could also, of course, be a hard man when circumstances demanded. I was reminiscing this week with Tony Higgins, who used to run the Scottish Professional Footballers Association. John was a great football man and, for many years, sat on various quasi-judicial panels thrown up by the Scottish game. At one time there was a Transfers Tribunal which adjudicated on the value of players.

John was presiding over a session at which the chairman of a Scottish football club was demanding a valuation of £500,000 on a prize asset. The tribunal halved that figure. When John intimated their decision, the aggrieved chairman barged out, casting a fierce glare in his direction. John murmured to Tony: “The last time a man looked at me like that, I sent him down for 30 years.”

Reading the obituaries, I was interested in John defining his greatest achievement as stopping the Scotland Act of 1998 giving Holyrood the power to sack judges, on the vote of MSPs. This seemed remarkable on several counts, not least that the option was advanced in the first place. Today, we associate politicians sacking judges with Poland and Turkey and it is generally thought to be a bad thing.

The reminder that political liberals who were at the heart of planning devolution should have proposed such a power seems strange. I can only think it must have reflected an optimism of the age. In the imaginings of its architects, the Scottish Parliament was to be different, consensual, filled with reasonable people, elected by proportional representation, taking bipartisan decisions around their hemispheric chamber. Judges would have no reason to be concerned.

Some of us did not require the benefit of hindsight to think all of that highly unlikely, but what few would have predicted is the extent to which the accretion of power towards the centre, as close to ministerial control as possible, would become the defining characteristic of Edinburgh governance. The combination of institutional empire-building and the Nationalist belief in everything being organised on a Scotland-wide basis as part of their entitled fiefdom has proved powerful. Judges would have had to ca’ canny, like so many others.

I looked back to John’s speech in the House of Lords when he effectively killed off the plan. “If pressed,” he said, “I could give examples in my lifetime of judges who have been appointed to the bench who should not have been appointed and would not have been appointed but for political and cronyist influences.” He did not wish to see this carried over into the new regime, far less extended by giving politicians the right also to remove judges. He elaborated: “We must avoid the danger that judges can be removed from office by politicians. Judges who can be so removed cannot be independent because independence in practice means freedom from government pressure, freedom from populist pressure and freedom from political pressure. It means that we, the judges, do not have to look over our shoulders at what others are saying about the kind of decisions we take.”

Not only were these words self-evidently wise but also, by implication, prescient about how devolution would work out. How many in Scotland today are constantly looking over their shoulders for fear of incurring political displeasure? How many quangos, advocacy groups and third sector organisations which once fought their corners vocally and were expected to do so are now extremely wary of upsetting the puffed-up rulers who control both appointments and purse-strings?

If there is any upside from the travails of Police Scotland and the cowed, non-barking dog that is the Scottish Police Authority, it lies in the way they have given centralisation of the justice system, unhealthily close to ministerial control, an extremely bad name. Never allowing Scotland’s politicians to forget that separation of powers within the legal system is an essential democratic safeguard, rather than an optional inconvenience, would be a decent memorial to Lord McCluskey.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was a defender of the House of Lords, where he was an active member for 40 years. This certainly had nothing to do with social status but reflected his respect for the expertise it contained and the quality of debate which was possible – not least when it involved highly significant issues about the evolution of the legal system. The question arises – where could such debate take place in Scotland? The procedures of Holyrood scarcely encourage it, even where the expertise exists.

As much as I oppose the House of Lords as currently constituted, I support the existence of a second chamber where speeches are not read from prepared scripts or confined to five minutes. Until Scotland provides such a forum we must rely on whatever channels are available to help safeguard us from bad legislation and meddling with our legal system that have not been thought through beyond the populist premises which appeal to politicians.

It’s worth remembering that in one of his last public interventions, Lord McCluskey torpedoed just such a plan by applying a rigorous critique to the idea of abolishing the corroboration principle within the finely tuned Scottish legal system.

Now that he is gone, who will fire such missiles without fear or favour? In today’s Scotland, there are not many obvious candidates.