Bill Jamieson: Giving young £10k is no solution to living standards crisis

Of all the potential threats to our stability and well-being, arguably the most challenging is the widening gap in wealth between old and young across the UK.

Never in modern times has there been an expectation among younger people that they would not match the standard of living of their parents. Home ownership now looks beyond the reach of many. In the era of zero-hour contracts, well-paid jobs are hard to find, and employment itself has seldom looked more transient and insecure.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the past 70 years, we have relied on the permanence of rising expectations – that we could look forward over time to a general increase in living standards. Research by the Intergenerational Commission finds that people are more pessimistic in Britain about the chances of the next generation having “better lives” than the one before it – compared with almost any other country.

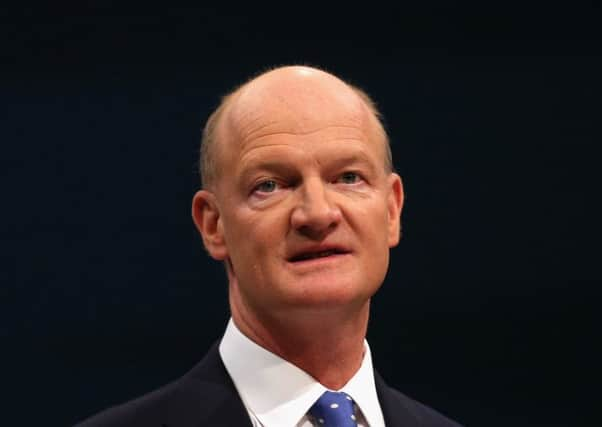

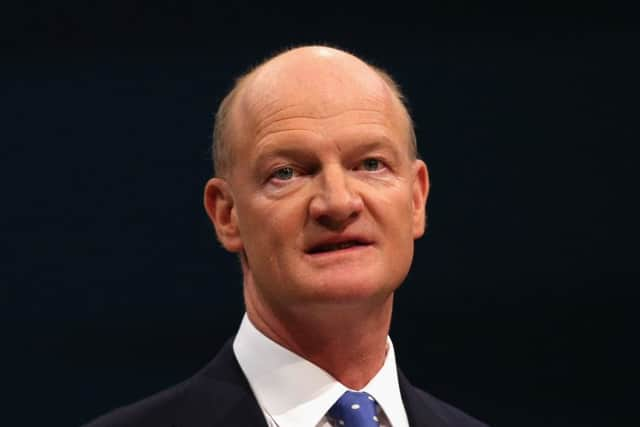

The belief in rising expectations has been an important foundation for our political institutions and our social peace. A breakdown here portends serious trouble. That is the background to the report this week from the Resolution Foundation think-tank. Its chairman, Lord Willetts, has warned that the contract between young and old has “broken down” and that radical change is needed.

“Intergenerational fairness” is the slogan. Among its proposals are calls to tax pensioners more to better fund the NHS; scrap council tax and replace it with a new property tax targeting wealthier homeowners; and create a new “lifetime receipts tax” to replace inheritance tax.

The most eye-catching suggestion is a call for a £10,000 payment to be given to all young adults at the age of 25 to help pay for a deposit on a home, start a business or improve educational skills.

An NHS “levy” of £2.3 billion would be paid for by increased national insurance contributions for those over 65 and still working. If National Insurance were imposed on income from private pensions, it would raise about £350 million a year for each penny on the rate.

Meanwhile funds for the payment to every young adult would be raised by abolishing inheritance tax and replacing it with a lifetime limit for recipients of £125,000 before taxes kick in. The commission estimates this would raise £5 billion.

The problem is well set out by Lord Willetts – as one would expect from a former Conservative government minister long nicknamed “Two Brains”: the evidence of growing intergenerational inequality is as indisputable as it is worrying. And he has, sensibly, ruled out the traditional knee-jerk solutions – extra borrowing (unfair on the younger generation) and higher taxes on the working population (when younger people in particular have not seen much, if any, increase in their pay). But reading his policy prescriptions, it is hard to escape the impression of a slight dottiness: less the work of “Two Brains” than that of Professor Brainstorm. Into his lecture theatre he has wheeled a huge clanking edifice, a steam-billowing construct of convoluted tubes, wheels and ratchets, fed at one end by a queue of wealthy pensioners for fleecing and spewing out at the other folded money in neat £10,000 bundles. It has the deceptive illogic of the artist M. C. Escher’s drawing of the upward-flowing waterfall.

Problems tumble out. Scalping working pensioners by imposing National Insurance might seem an easy hit. But many are part-time jobs and a large number are self-employed. The reason they have returned to work is that they are financially squeezed. And a tax hike here would be an insult to those who have paid taxes and National Insurance over a working lifetime of 40 years or more.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMoreover, his proposal would effectively raise the “tax rate” on retired folks’ income from 20 to 32 per cent – in effect a 60 per cent tax rise that would insult pensioners.

As for the £10,000 payment to 25-year-olds, why is this to be paid to everyone, regardless of financial circumstance or family income? How has this figure been arrived at? It seems arbitrary – barely enough for a down-payment on a house. And how is the spending of the 25-year-old to be policed to ensure that it goes towards the deposit on a home, to start a business or improve educational skills? Would not a surveillance scheme have to be put in place?

Another suggestion for getting wealthier pensioners to meet the cost of long-term care is a 20 per cent tax on all inheritance up to £500,000 and then 30 per cent tax above that figure – more complexity, and yet more anomalies thrown up. As Nerissa Chesterfield of the Institute for Economic Affairs points out, “not only does this make the system far more complicated than it needs to be, it also means that the 50-year-old on the minimum wage who has saved up, say, £50,000 for his children would now be taxed at a 20 per cent rate rather than zero. Hardly helpful for those who need it most.”

As for the NHS, it is hard to avoid the suspicion that even if we devoted the whole of our GDP to it, there would still be a funding shortfall. Why not face reality and introduce a £5 consultation fee for GP visits? It’s politically toxic of course – no government would dare to introduce it. But then the remedies proposed by Lord Willetts are scarcely more acceptable.

What other, more practical solutions, might the Resolution Foundation have advanced?

There may be ways to incentivise builders to concentrate more on starter homes; to reduce the tax take for young earners or raise the threshold for payment ofNational Insurance contributions.

There is also, I suspect, more of a readiness among families to extend financial help to their offspring than is accounted for by HMRC data.

Better, surely, to address generational inequality by encouraging life-time gifts rather than punishing them. These might stand a better chance of adoption than the Lord Willett’s improbable tax-threshing monstrosity.