Bill Jamieson: Brevity is the soul of thrift for Osborne

With the hefty November Autumn Statement barely four months old, the EU referendum looming on 23 June constraining the Chancellor’s room for policy manoeuvre and his options for tax changes – up or down – notably curtailed, what purpose is served by a “full-on” traditional budget at this time?

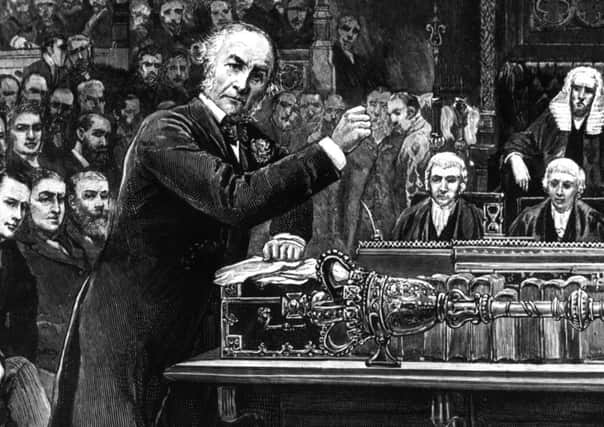

At least we should be spared a marathon budget of the type delivered by William Gladstone. In 1853 he banged on for four hours and 40 minutes. Better, surely, to aim for the succinctness and brevity of Benjamin Disraeli. In 1867 he wrapped up the budget in just 45 minutes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe best option for Osborne on Wednesday would be to aim for a budget of the Disraeli type – no complicated changes that could backfire in the run-up to the referendum – major reform of the system of pension tax relief has already been shelved for precisely this reason – and no micro innovations that could backfire – the pasty tax, for example.

A budget of anything more than 45 minutes would be an indulgence – and a tell-tale sign that he has succumbed to the temptation to fill up the time with the sort of fiddling and tinkering that Gordon Brown turned into such a wearisome art.

So what are the points that matter, and what should we look out for on Wednesday?

There is an income tax anomaly that can be addressed. And there is every possibility that the headlines on Thursday will focus on changes to the threshold for the higher 40p rate of income tax. He may not be able to go the whole hog and raise the current £42,385 threshold (rising to £43,000 in 2016-17) to £50,000 which is his ambition over this parliament. But a useful start could be made and a declaration of further intent underlined.

He may also reinforce his commitment to raising the personal allowance – income that is free of tax. This is currently £10,600, and his ambition is to raise this to £12,000. Achieving both of these objectives by 2020 would cost an estimated £8 billion a year. Given the state of the budget books, he will need to approach this ambition with caution.

The Chancellor’s biggest constraint remains the budget deficit and the continuing rise in the government’s overall net debt. This is a massive issue – and one that rarely features in Scottish politics. With figures last week showing that Scotland’s deficit in the last financial year had risen to almost £15bn, equivalent to almost ten per cent of Scottish output and close to double the comparable figure for the UK as a whole (just under five per cent) it is not hard to see why this omerta continues to prevail at Holyrood.

For Osborne it is not so easy to ignore. Indeed, the Fiscal Mandate specifies that the UK must run a budget surplus in 2019-20 (and in “normal” economic years thereafter). And developments since the Autumn Statement have not been favourable to this legal requirement of a budget surplus.

As it is, the Chancellor is faced with the continuation of higher than expected government borrowing. Cumulative borrowing in the year to January is running £5bn higher than the Office for Budget Responsibility 2015-16 forecast of £73.5bn. For 2016-17 the OBR has forecast a fall in Public Sector Net Borrowing to £49.9bn (2.5 per cent of GDP). As for overall net debt, this is forecast to keep rising – from £1,599bn this fiscal year to £1,652bn next.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe “good news” here is that at least net debt as a percentage of GDP falls from 82.5 per cent to £81.7 per cent. That this is seen as progress is a measure of how deep in the stew the government’s finances remain.

Progress in deficit reduction now faces a weakening economic outlook. Back in November, the OBR forecast UK GDP growth of 2.4 per cent in both 2015 and 2016. But a slowing world economy – the G20 has piously called for collective action to use fiscal policy to strengthen growth – continuing problems in lifting the Eurozone’s lacklustre growth rate and Western central banks running out of tools to effect economic uplift, make it likely that on Wednesday the growth forecast for 2016 will be shaved down to 2.2 per cent.

But if Osborne is constrained in how much stimulus he can deliver, his hand is equally tied when it comes to further austerity. It is difficult to see how departmental spending limits could be reduced further, and in any event such a move would be politically dangerous ahead of the Brexit vote.

However, it is not all downside risk. With current forecasts pointing to a £10bn budget surplus by 2019-20, the Chancellor has some headroom to “ease the squeeze” but still meet his balanced books target. Meanwhile, interest rates are set to stay lower for longer, bringing down debt service costs, with borrowing costs across the economy falling by as much as £4bn by 2020.

A few other points to look out for. The Budget could provide a chance to clear up an income tax anomaly. As the personal allowance tapers away by £1 for every £2 of income over £100,000, an effective tax rate of 60 per cent is paid on income between £100,000 and £121,000. This could be amended.

Fuel Duty could be raised by 2p a litre in the wake of further falls in the oil price. And the Chancellor could rake in more money from the banks by tapering the rate at which the eight per cent surcharge on Corporation Tax is reduced.

Overall advice this weekend? Keep it short, Mr Osborne. This week, less really would be more.