Astronauts to test asteroid mining kits devised by Edinburgh University scientists

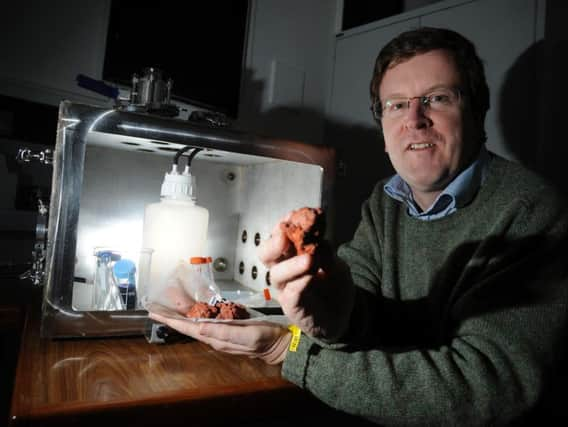

Astronauts are to test the world’s first asteroid mining devices, developed in Scotland, in an advance that could open up a new frontier in space exploration. Prototype kits devised by scientists at the University of Edinburgh, are being sent to the International Space Station (ISS) to study how microscopic organisms could be used to recover minerals and metals from space rocks.The groundbreaking study could aid efforts to establish manned settlements on distant worlds by helping develop ways to source minerals essential for survival in space.Tests will reveal how low gravity affects bacteria’s natural ability to extract useful materials – such as iron, calcium and magnesium – from rocks, researchers say.Their findings could also help improve the process – known as biomining – which has numerous applications on Earth, including in the recovery of metals from ores.Astrobiologists from the UK centre for astrobiology at the university developed the matchbox-sized prototypes – called biomining reactors – over a 10-year period.Eighteen of the devices will be transported to the ISS aboard a SpaceX rocket, which is scheduled to launch on Sunday from Cape Canaveral in Florida.Upon arrival at the space station, small pieces of basalt rock – which makes up the surface of most asteroids – will be loaded into each device and submerged in bacterial solution.Tests will be conducted in low gravity to find out how conditions on asteroids and planets such as Mars might affect the ability of bacteria to mine minerals from rocks found there.The experiment will also study how microbes grow and form layers – known as biofilms – on natural surfaces in space. As well as providing insights into how low gravity affects biofilms, the findings will also improve understanding of how microbes grow on Earth.The rocks will be sent back to Earth after the three-week experiment, to be analysed by the Edinburgh team in a lab at Stanford University.The project is led by the university, with the European Space Agency and the UK Space Agency and funded by the Science and Technology Facilities CouncilProfessor Charles Cockell, of the university’s school of physics and astronomy, who is leading the project, said: “This experiment will give us new fundamental insights into the behaviour of microbes in space, their applications in space exploration and how they might be used more effectively on Earth in all the myriad way that microbes affect our lives.”Dr Rosa Santomartino, also of the university’s school of physics and astronomy, who is leading the study of the rocks when they return, said: “Microbes are everywhere, and this experiment is giving us new ideas about how they grow on surfaces and how we might use them to explore space.”Professor Cockell, has been involved in a number of pioneering studies.An earlier study conducted by Professor Cockell involving the ISS involved taking some rocks from a cliff in Devon and flying them on the outside of the manned space laboratory for 18 months to determine whether any microbes survived in space. The research found that one species survived. Further studies found this was partly due to it forming bio films. It was also very resistant to ionizing radiation.