William Soutar: The poetic genius written out of Scottish history

When Perth decided to honour its greatest poet by renaming the library theatre, the man tasked with the job assumed there was a spelling mistake in his brief. Being a helpful sort of chap, he corrected this, so that the large gold letters on the side of the building read The Souter Theatre.

Everybody in Perth has heard of Stagecoach boss, Brian Souter. The 20th century poet William Soutar, friend of Hugh MacDiarmid, creator of some of the most hauntingly beautiful lines ever written in Scots, is less famous in his home city. Further afield, outwith university literature departments, he is hardly known at all – and yet, 80 years ago, he was acclaimed as “probably the greatest living Scottish poet”.

Advertisement

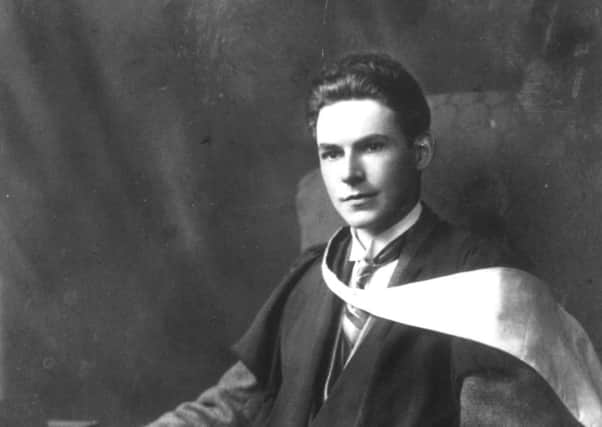

Hide AdSoutar was born in 1898, son of a master joiner. Young Willie was a mischievous scamp who grew into a handsome, athletic teenager. He wrote some terrible poetry, as teenagers will. When he left school, he served in the Royal Navy and witnessed the surrender of the German fleet at the end of World War I. In 1918 he was invalided out with pains in his legs. He didn’t know it then, but the vigorous, irreverent youth was on his way to a new identity. Within a few years he was poor Willie, too unwell to hold down a job after graduating from Edinburgh University, bedridden by 32, dead by 45 of tuberculosis, after spinal arthritis turned him into a living statue.

So far, so tragic. But this is only half the story.

While his friends were out in the world, building their careers, marrying and starting families, Soutar was staring at the same four walls, day after day, entirely dependent on his parents. (Few poets write so feelingly about time.) The temptation to sink into depression was there, and sometimes he went under, but when he resurfaced he set about turning his desperate situation to advantage.

Much as we love the romantic idea of innate genius, the truth is most writers are not born but made – which is to say, self-made. Soutar used all that dead time to turn himself into a poet.

He wrote continually: diaries, dream diaries, riddles, epigrams, whigmaleeries, bairn rhymes, and short lyrics in both English and Scots. Not everything he wrote has stood the test of time, but the best is still powerful. Take the poem, Autobiography, which summarised his life – and anticipated his own death – in nine beautifully restrained lines.

Out of the darkness of the womb

Into a bed, into a room:

Out of a garden into a town,

And to a country, and up and down

The earth; the touch of women and men

And back into a garden again:

Into a garden; into a room;

Into a bed and into a tomb;

And the darkness of the world’s womb.

In some ways, he was a timeless writer, drawing inspiration from nature, as poets always have. At the risk of making him sound like a Sixties hippy, some of his poems conjure a tranced, hyperaware state at once microscopic and cosmic. He could do lyrical, musical, poignant, folksy, humorous. The macabre comedy in some of his whigmaleeries is almost medieval. But he was always engaged with the world around him. He wrote The Children about the bombing of Guernica in 1937, and was a passionate promoter of the Scots language – an intensely political issue then as now. Seeds in the Wind, his collection of bairn rhymes, was dedicated to his adopted sister Evie but published with a larger purpose in mind. If the Doric is to come back alive, he wrote, it will come first on a cock-horse.

Will a television executive ever greenlight the drama series begging to be written about the writers and artists of the 20th century Scottish Renaissance movement? (Bloomsbury in kilts, people!) If it happens, at least one episode will feature William Soutar.

Advertisement

Hide AdWe will see the bedridden, charismatic, still strikingly good-looking poet receiving a stream of visitors. Some come to tell him their troubles, others to rock with laughter at his jokes.

Afterwards, alone, his face shows the strain. Only with a few close friends is he able to take off the mask.

Advertisement

Hide AdOne of these is Hugh MacDiarmid, the movement’s megalomaniacal genius. At first he is a mentor, publishing the younger poet in his anthology Northern Numbers. But as Soutar’s work wins admiring reviews, a new edge enters the friendship. There are noisy, whisky-fuelled arguments late into the night. For Soutar, these are amicable disagreements.

MacDiarmid’s feelings are more complicated. He is forever one step away from destitution, taking on more than he can manage to keep the wolf from the door, while Soutar lies abed, waited on hand and foot, with all the time in the world to polish his glittering lyrics. Of course MacDiarmid envies him – but what sort of heel envies an invalid, confined in a single room?

After Soutar’s death, none of this should matter. But in an unlucky twist of fate, when Jack Soutar is looking for a literary man to edit a posthumous collection of his son’s work and secure his reputation for all time, he asks Hugh MacDiarmid. MacDiarmid needs the money – he always needs the money – but that newspaper review calling Soutar the greatest living Scottish poet still rankles… He writes what must be the least-generous introduction to a collection of poems ever.

Here’s a small sample: “the infrequency with which his muse takes wing”; “the unexciting jog-trot of his verse”; and (after the Times Literary Supplement called Seeds in the Wind a minor classic) “the adjective ‘minor’ must be stressed”. As an act of score-settling by a monstrously insecure ego, it would almost be funny, if the damage to Soutar’s reputation hadn’t proved so enduring.

I’m not going to refute MacDiarmid’s criticisms by quoting line by line from Soutar’s verse. Instead, I suggest you do yourself a favour and read The Tryst, or The Halted Moment, or Scotland, or Yesterday, or Black Day, or The Wind (first line: “Wha wudna be me”). I promise, the world will look a wee bit different afterwards.

Ajay Close is a past William Soutar fellow, and secretary of the Friends of William Soutar Society.