Think Brexit’s bad? British history is steeped in violence – Bill Jamieson

Great novels can be a balm to the soul. In a desperate desire to escape the deepening horrors of Brexit news, I have hugely enjoyed a retreat into Tombland, CJ Sansom’s epic blockbuster novel on the 1549 Kett’s Rebellion.

Of this event, surprisingly little is known. But across East Anglia, the West country and the south-east of England, some 11,000 people were killed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTombland, a current top seller running to 800 pages with a 50-page historical appendix – a Kindle version is recommended as the print version will stretch the biggest handbag – is not only an engrossing account of the uprising in Norwich but also richly informed.

While this a novel, Sansom has done copious research to ensure authenticity: it is packed with historical detail drawn from factual accounts. I cannot recommend it highly enough. What an ideal diversion, you may think, from our deepening Brexit impasse.

The book is set in a different era, and in a country barely recognisable today. And such violent, bloody eruptions are surely rare. After all, we tend to think of Britain – England especially – as a peaceful, settled place with a settled constitution, secure institutions with a model parliamentary democracy. It is not prone to civil eruptions like the French with their gilets jaunes, “yellow jackets”. Rather, England likes to see itself as an amicable land of happy if at times eccentric people, often depicted on English Heritage websites as a rural idyll, populated by Morris dancers. Kett’s rebellion was surely a freak event, with no historical antecedent or aftermath.

But was it so freak? Modern political history, tightly focused on events in parliament, may well be portrayed as one of change achieved within the framework of an enduring constitution and without violence or civil disturbance.

But it has not always been so. Indeed, periods of violent upheaval have been so frequent as to beg the question, “which is the exception and which the rule?” For there is another history of these islands. Kett’s Rebellion, unusual though it may have been in slaughter, was no isolated event. It was preceded by the Peasants’ Revolt (1381); the constant rebellions of 1135-1154; the Wars of the Roses (1485-87); the Cornish Rebellion (1497); and the Lincolnshire Uprising (1536).

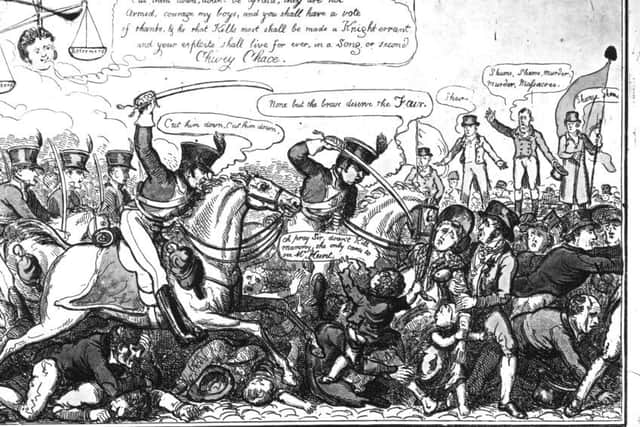

It doesn’t stop there. There was Wyatt’s Rebellion (1554); the Gunpowder Plot (1605); the Leveller uprisings (1607-46); the English Civil War (1642-51); the Jacobite Rebellions (1715, 1745); the Peterloo Massacre (1819); the Chartist unrest (1838-1858); the Easter Rising and Irish War of Independence (1916); and the Battle of George Square, Glasgow (1919). More recently there has been the Miners’ Strike, Poll Tax riots and London riots (1984-2011).

Even within relatively amicable periods there have been gridlocks and stand-offs which have brought down governments and which amply deserve the word ‘crisis’: the divisions over the Corn Laws (Robert Peel); Irish Home Rule (Lloyd George, Arthur Balfour, Bonar Law); free trade versus protectionism (Joseph Chamberlain); appeasement and war (Chamberlain, Churchill); Suez (Eden), the three-day week (Heath) and industrial unrest (Callaghan). These were events which raised searching questions, not simply on policy but on the legitimacy of government.

History has often proceeded by long periods of amicable nudge, but it is also marked by violent shove. Set against these, the parliamentary deadlock of Brexit and the potential collapse of our longest lasting political party hardly bear comparison. Yet the deepening gridlock over Brexit is more than a disagreement over policy, or even the legitimacy of a minority administration – a division now so extreme that the authority of Theresa May, widely described as “Prime Minister in Name Only” has been overtaken by Parliament and a set of Parliamentary votes put forward by Oliver Letwin, the “Prime Minister in All but Name”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the fault line is even deeper than “Who Rules?” It goes directly to the issue of national identity and who we are as a people. As Theresa May said in her broadcast on Tuesday, “This is a decisive moment in the story of these islands”. Fractious and hair-splitting though the procession of parliamentary motions and amendments may seem, this is an underlying issue of great moment, and there is no certainty that either a general election or referendum is likely to bring a settled outcome. Indeed, many fear that they will deepen the current mood of anger and division, with a fracturing of the party system as we know it.

Thus is our history being made. It is tempting to think that on Brexit we must now surely be near the end, or the beginning of the end. I am not so sure: given the likelihood that recent events have marked a sea-change in national politics and with consequences to follow, we may only be near the end of the beginning.