Lesley Riddoch: Scotland's national growth is about more than just the economy

The Irish abortion referendum result, announced the day after Scotland’s Growth Commission report, is proof that social change can be a bigger national game-changer than the relentless pursuit of economic growth. Nicola Sturgeon should take note.

The two-thirds vote for legalization was far in excess of the “dead heat” predicted by Irish pollsters and has ended Ireland’s century-long status as fun-loving, slick-talking, social conservatives almost overnight. Now the British women and equalities minister, Penny Mordaunt, says similar hopes for change in Northern Ireland “must be met”. That’s not just an unlikely outbreak of feminist solidarity by a leading Tory woman but also a necessary bit of political catch up. There’s always been unspoken competition amongst the nations of these Isles over cultural clout, population growth, inward investment, economic strength and social liberalism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSuddenly she is on the wrong side of history, with abortion and equal marriage still outlawed in regressive Northern Ireland and unable to be properly discussed because of the deadlock that’s collapsed Northern Ireland’s power sharing Executive. Irish politicians have worked across party divides to tackle a divisive moral issue, but have reaped a substantial reward – the creation of a modern, secular Irish state, almost a century after independence, in which religion is finally a matter of private conscience not state policy. Northern Ireland, unable to agree even on a Language Act, has been hopelessly left behind. And suddenly that matters to the British Government – not just because of Theresa May’s dependence on Unionist political support but because the tectonic plates of identity and allegiance in the province are moving at lightning speed, thanks to Brexit.

It’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that inhabitants of Northern Ireland could soon demand a cross border poll on reunification with the South – not likely still, but no longer unthinkable. If that happens, the radicalising effect on Scots would be enormous, making a second indyref irresistible and leaving Great Britain a mere shadow of its former imperial self.

So even though the English public recently told pollsters they would rather lose Ulster than Gibraltar, and even though Northern Ireland is still an economic liability, Theresa May knows a vote for reunification would be a ferocious blow to a friendless and rudderless Brexited Britain.

Things are afoot.

A poll at Christmas 2017, suggested 58 per cent of NI folk want to remain in the customs union and single market after Brexit and in the event of a hard Brexit, 48 per cent would vote for a United Ireland.

Earlier this month, the independent unionist MP Lady Sylvia Hermon said she feared Brexit could result in a border poll leading to a united Ireland; “In my lifetime I never thought I would see a border poll. I am now convinced that it will probably happen.” Then the Times reported Theresa May was not confident of victory in such a poll after a confrontation with arch Brexiteer, Jacob Rees-Mogg. Last week, a poll in the province suggested the Remain majority had surged from 56 per cent to 69 per cent.

And that’s without any sniff of a formal reunification campaign.

So what’s happened?

Firstly, there’s been slow and steady demographic change - the 2011 census, asked parents what religion their children were being brought up in. 49.2per cent said Catholic and 36.4 per cent Protestant or other Christian. And in last year’s Stormont elections, the long predicted moment finally happened; the two unionist parties, won 38 seats in the 90-seat assembly, whilst the two Republican parties won 39. Of course, thanks to the mechanisms ensuring coalition government by the largest party from each “side”, it made no great difference at Stormont. But psychologically that was a huge moment that went largely unnoticed in the rest of the UK. Young voters in Northern Ireland got the message though. The future will not look like the past.

Secondly, life in the Irish Republic looks much more attractive these days compared to life in Britain. Public services – once so much better across the water – are now better in the Republic. Divorce, same-sex marriage and now abortion are legal. So which is the progressive and which the regressive society today?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIreland’s new Taoiseach Leo Varadkar embodies the change. He is a half-Indian, openly gay prime minister. But perhaps even more significant, these personal characteristics were hardly remarked upon during the race for the Fine Gael leadership last year. Once upon a time, Northern Ireland Prods looked down their noses at their socially backward country cousins. No longer.

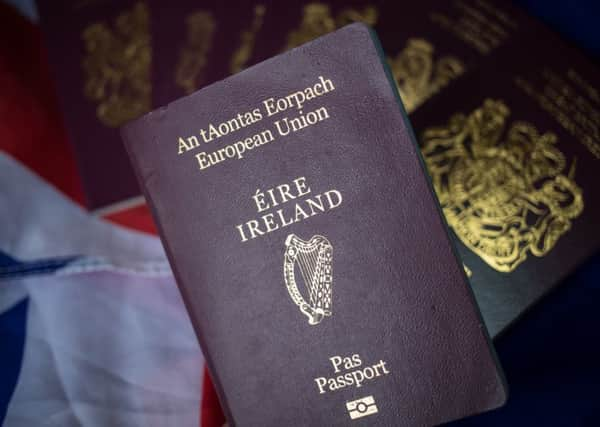

And thirdly, young Ulster folk have found their own escape from Brexit – their automatic qualification for an Irish/EU passport. That offer of Irish citizenship is not just a technical fix, it’s the embodiment of a caring and connected attitude towards the North in Dublin, contrasting starkly with the clear evidence that London is trying to find a way to dump its responsibilities to the whole island.

The prospect of life as part of an internationalist, ethnically mixed and outward-facing Ireland is infinitely more attractive to most young Belfasters than life in the slow lane within Brexited Britain. Will that disaffection come to a head soon? Can Protestant supporters of a reunited Ireland find a political party vehicle for their cause?

Who knows. But whilst the downsides of Brexit may take a bit of explaining in Scotland (apart from the obvious betrayal on fisheries) they are crystal clear in Ireland.

For Scots, Europe is reached by a lengthy ferry, train or plane journey. For folk in Northern Ireland, Europe is a mere car, train or bicycle trip away. Perhaps that’s why the political impact of Brexit has been faster and more tangible in Northern Ireland than on this side of the Irish Sea.

Of course, life in the Irish Republic isn’t a bed of roses. And Ireland’s membership of the Euro has been deeply problematic – especially after the 2008 financial crash.

But Europe and the transformation of Ireland are clearly intertwined. So the people of Northern Ireland could yet be the first to take a Brexit-related step away from Britain.

Can Scotland learn from all this? We live in an age and a country obsessed with economic growth and the cold business of accumulating cash. Mere democratic transformations are routinely downplayed and underrated.

But that’s a mistake. Social change in Ireland could be a bigger motor for economic change here than anyone has yet considered.