Iolaire 100: Lewis to commemorate when 200 returning soldiers died yards from home

As 1918 ended, the island of Lewis was caught up in momentous events, soon to be overtaken by a disaster of unimaginable proportions.

Scotland tends to have a slightly schizophrenic relationship with its Hebridean fringe. It rejoices in glorious images while lapsing too readily into caricatures of factors which create “difference” – language, faith, values.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese are generalisations, of course, shaped over centuries. Much is rightly being heard of events on Lewis exactly a century ago. Amidst the deep poignancy of commemoration, there should also be food for contemporary thought.

By the time the war ended, an island of 29,000 people had sent 6,172 men to oceans and trenches where fully a fifth of them gave their young lives. Though engulfed by grief, there was intense activity at home in the hope of a better future.

Lewis was a materially poor place beset by overcrowding of crofting villages, insanitary housing and the scourge of TB. In 1912, the Dewar Committee – investigating medical provision in the Highlands and Islands – concluded: “That such a condition of affairs as we found in Lewis should exist within 24 hours of Westminster is scarcely credible. Nor is it creditable from a national standpoint.”

The critical issue was access to land to create crofts on which homes could be built. For returning servicemen, that was unfinished business to be resolved at the earliest opportunity.

A champion had emerged in their absence. The Reform Act of 1918 created a Western Isles Parliamentary constituency. Its first representative, Dr Donald Murray, a Liberal and respected Medical Officer of Health, was confirmed on 28 December 1918 – a beacon of hope for the peacetime ahead.

Early in the year, a maverick factor emerged with the purchase of Lewis by Lord Leverhulme, with plans to turn Stornoway into “Port Sunlight of the North” – a regimented industrial town devoted to fish canning.

There was plenty potential for support. However, Leverhulme promptly set his face against crofting as inimical to a disciplined work ethic. It was an unnecessary conflict and within a few years, for reasons unconnected to Lewis, his schemes collapsed.

For most on the island, this political ferment was secondary to the immediate fact that those who had survived four years of war were finally coming home. Then the ultimate tragedy struck.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

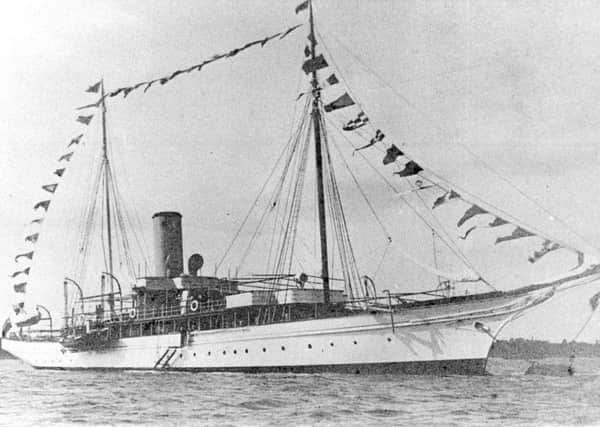

Hide AdI looked back at an article I wrote on the 75th anniversary of the Iolaire’s loss. The tragedy still remained remarkably private to the island mainly because of reluctance to disturb the intense sensitivities it evoked.

For example, the hero who saved 40 lives by getting a rope ashore, John Finlay MacLeod, never spoke to his own son about the Iolaire until the outbreak of the Second World War and did not mention it again for another quarter century. Even for the 75th anniversary, there were no commemorative events though all survivors had passed on.

I wrote then: “Perhaps the most surprising omission is the absence of any serious research into the disaster’s subsequent impact on Lewis and its communal psyche … Perhaps those who were close were too close and those who were outside had no point of access to private grief.

“In any case, within a few years, could the horror of 200 lives lost on the Iolaire have been separated from a thousand Lewis lives lost in the First World War or from the trauma soon to follow of another culling of this lost generation, as the ‘Metagama’ sailed for Canada, the average age of human cargo just 21?”.

With this centenary, there has come a time when Lewis wants the Iolaire to be remembered and understood – for the sacrifices made by peripheral places that never asked for much in return and an understanding that traumatic aftermaths are measured not in years but generations.

As life continued amid adversity, the battle for land was at least partly won – which largely explains why, in spite of everything, there are still 19,000 people on Lewis today.

For readers interested, an excellent centenary book has been published by Acair of Stornoway – Call na h’Iolaire/The Darkest Dawn by Malcolm Macdonald and Donald John MacLeod