Why political opinion polls may well be harming our democracy – Alastair Stewart

Are we all expert amateurs now? That's the question that's been rattling around in my head since 92,153 Conservative members elected Boris Johnson as their next leader.

Continuous polling is no doubt well underway as to his popularity: Will Boris win or lose a general election? Has he made Scottish independence likelier? What colour of tie should he be wearing? There's may have even been private polling about how the Prime Minister's private life and his girlfriend are presented to the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEvery political leader indulges polling, but it's also the basis for endless commentary and interpretation. Every publication, politician, party or punter deciphers a poll how they want to see it. Lord Ashcroft's recent finding that 52 to 48 per cent of 1,000 Scots surveyed now favour independence will inevitably be the starting gun for Indyref2 in the weeks ahead.

The problem with polling is so little thought is given over to the methodology behind it. Psephology is a dry topic at the best of times, but it has become an overused crutch, a weekly barometer for 'when' a second vote on Scottish independence will happen.

In 2016, I arrived home from Spain just as Nigel Farage was about to give his concession speech at about midnight on the day of the EU referendum. By 8am the following day, it emerged that poll after poll had gotten it wrong by more than a million votes.

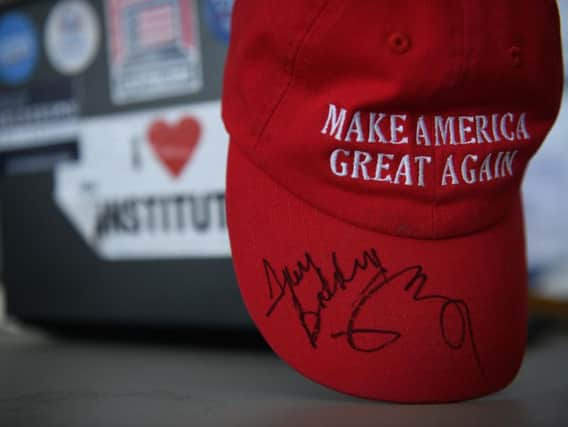

A month later, "Make America Great Again" Trump hats were being grabbed up for posterity. A bit of lark, he'll never win, keep it as a historical memento. By November, the same pollsters found themselves welcoming President-elect Donald Trump who, while didn't win the popular vote, still won the electoral college.

Political parties and candidates employ polling to scratch the obligatory tactical itch. Does their 'message' convey what it should, is it working on the right demographic, where are we on branding and focus? Political surveys are as much a science as finding out audience reactions to preview film screenings.

In 1948, Republican Thomas Dewey faced off against the incumbent president Harry Truman. The Chicago Daily Tribune, a Republican-leaning paper at the time, ran a poll predicting a decisive win for Dewey. So confident in their analysis were they that the paper went to print with the headline: "DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN." Suffice to say there's a wonderful picture of the victorious Truman posing with it.

Exceptions to the rules are critical to understanding the over-reliance we have on surveys now. It would be remiss not to argue that opinion polls, either consciously or otherwise, incentivise and galvanise action. Behavioural science is rooted in the premise that human crowds will go with the majority, the socially acceptable, the safe choice (James Surowiecki's 'The Wisdom of Crowds' splendidly dissects this).

A sampling of voters typically includes around 1,000 people. For all the efforts that can be made to weight the target respondents, to make it as economically or socially 'real' as possible, you cannot predict human nature. The day, the time, the place – all can yield a different, visceral response in the same human being.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDatasets are unpredictable and there’s a nasty habit ignoring the methodology behind them. The most disturbing development in Scottish society in recent years isn't censorship by the state, but self-censorship - the fear of not going with the flow, or going against what's popular, of speaking out, particularly in public. If that's already a national habit, a public trait, won't that impact on polling, too?

When the Chicago Daily Tribune revisited their poll to see what went wrong, they discovered that Republican voters in their data had not only been over-sampled but that the survey had been conducted over the phone. The logic followed that as, in the 1940s, wealthier people had household phones, they were more likely to be Republican.

The myriad of methodologies behind polling that can affect the results is the exact reason it should be called a science. Science is not perfect; let's stop pretending it is. No one is saying surveys are rigged; such an accusation – while invariably true in some cases – is to undermine the hard work of people to uncover the country's views. In this, they serve as almost a weather gauge, and sometimes it looks like it's going to pour, but it doesn't.

To predicate policy on sampling, however, is another matter. The absurdity of surveys and polls serving as the starting guns is sophistry of the highest ilk. Why bother with elections otherwise?

Indeed, if we take our weather example further – how many among us trust weather apps to determine how we go about our day? Some look at the sky and say it will rain, others that they 'feel' it will and others still who hold up their phones and insist its prophecy is a decree to the heavens. Gut instinct and science, intertwined. How many say either one dictated how they went about their entire day?

The polling industry is useful. It's critical in many respects. It's also a mesh between the electoral-entertainment industry. Everyone loves a shock to the system. The issue now rests in the fact that short-sighted campaign tactics are determining government policy, far beyond focus groups, far beyond sampling.

In an age of the referendum, they're doing more harm than good to our democracy.