Where do Tories like Ruth Davidson go now – Joyce McMillan

In politics, there are few things more thrilling than a good resignation speech. When politicians decide to walk away from high office, they enjoy a rare moment of freedom to speak both truth to power, and the truth about the power they have so recently enjoyed; and from that moment, great and seismic flashes of insight sometimes emerge, as in Geoffrey Howe’s famously lethal speech of resignation from Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet in November 1990, or Robin Cook’s brilliant, forensic and unanswerable resignation speech against the Iraq War, in March 2003.

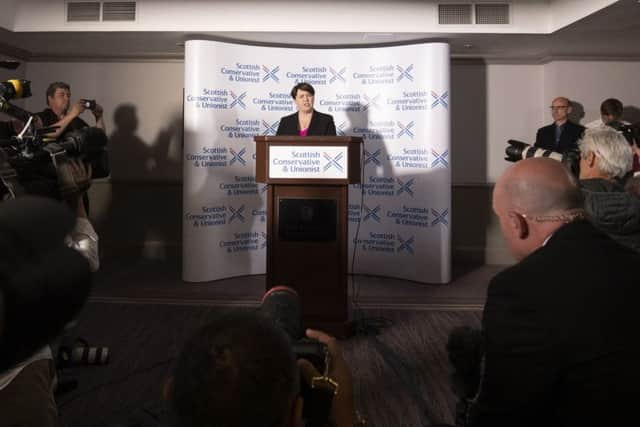

What was striking about Ruth Davidson’s resignation statement yesterday, though, was how mightily it strove not to be one of those memorable speeches, despite the fact that it was delivered at the height of the current crisis over the lengthy prorogation of Parliament, in the run-up to the declared Brexit date of 31 October. Historically speaking, perhaps the most striking aspect of the statement was Ruth Davidson’s refreshing honesty about the difficulty of combining the demands of full-throttle political campaigning with those of new parenthood. In a world where new mothers returning to work are often subjected to cruel pressures to act as though nothing has changed, Ruth Davidson has had the freedom, and the courage, to make it clear that she has new priorities; and in saying as much, she has struck a blow for every woman realistically trying to combine motherhood with work outside the home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeyond those personal motives, though, the Davidson resignation was the very model of how not to resign in the manner of Sir Geoffrey Howe. Despite harsh words about Boris Johnson in the past – Ruth Davidson was a fierce opponent of Brexit at the time of the 2016 referendum, openly accusing Boris Johnson of telling lies – and despite strong pressure to comment on the prorogations crisis, she made no direct criticism of him whatever.

Instead, she chose to accentuate the positive in her post-statement press conference, making it clear that she believes Britain should leave the EU with a deal, that she believes Boris Johnson is genuinely seeking a deal, and that in her view, those who say they are opposed to no-deal should demonstrate their good faith, in future, by committing themselves to vote for whatever deal the Prime Minister can achieve. She remained to the last, in other words, a representative of the kind of “moderate” Toryism whose voice has been increasingly drowned out, in recent months, by the shrill demands of far-right no-dealers. And the manner of her resignation – with its notable pledges of loyalty to the Conservative Party and the Prime Minister – suggests that far from giving up on her career, Ruth Davidson fully intends to return to front-line politics at some point, and to continue to campaign for that kind of approach.

All of which raises the question of whether she is right to do so; or whether the politics of moderate Toryism, and even the constituency for it, are now being swept away by much harsher historical tides and trends. A few years ago, I might have written a column about Ruth Davidson’s resignation bemoaning the foolishness of a Tory Party that once forfeited a huge section of its support in Scotland by adopting a combination of extreme neoliberal economics and jingoistic British nationalism, and now perhaps stands to do so again.

Now though – after a decade of exaggerated austerity at Westminster, and the introduction of savagely illiberal policies in areas ranging from immigration to the notorious rape clause, none of them vocally opposed by Ruth Davidson – the very idea of a liberal or centrist Toryism seems increasingly far-fetched; while the constitutional attitudes of many Conservative voters seem to have hardened, through the referendums of 2014 and 2016, into a kind of diehard anti-EU Unionism once found only on the margins of British politics.

In the last decade, in other words, the Conservative Party has changed, the political landscape has changed, and perhaps most crucially, the voters have changed; and one of the paradoxes of Ruth Davidson’s career in Conservatism is that some of Boris Johnson’s backers and closest associates are the very people who are responsible, via social media, for campaigns that deliberately ramp up the kind of hatred, fear, division and lack of mutual respect in politics against which Ruth Davidson made a heartfelt plea in her resignation statement.

Ruth Davidson is effectively a feminist in a party whose recent policies have cruelly damaged millions of women’s lives, whether they are mothers, carers or workers; a pragmatic pro-European in a party whose membership now overwhelmingly want to see the hardest Brexit possible; and a social liberal in a party whose divisive and fear-mongering policies in areas from crime to immigration actively militate against a true flourishing of liberal values. Some say that her striking ability to live with these contradictions, until now, is a measure of the shallowness of her political thinking, and of the fact that she is better at PR than at serious policy; some say that that judgment is too harsh.

Either way, though, the departure of Ruth Davidson seems to me like the end of a very long song; the song of the kind of pragmatic, comfortable-for-some Conservative Unionism that dominated the 1950s Scotland into which I was born. It was shaken but not destroyed by the coming of Thatcherism, it spent almost a generation in the political wilderness, and it appeared, under Ruth Davidson, to stage a brief and perhaps superficial revival.

Now, though, the shock of Brexit seems finally to have cracked its foundations in a wider but once-similar tradition of pragmatic British Conservatism. And only a fool would try to predict, in these volatile times, whether that shock will eventually lead to the emergence of a new centre-right party for an independent Scotland –- perhaps led, who knows, by an older Ruth Davidson; or to the steady assimilation of Scottish Toryism into the new-model right-wing Conservative Party of Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg, with which Conservatives of Ruth Davidson’s persuasion may find it increasingly hard to live, both as politicians, and as people.