What’s in a name? A mass of analysis

MANY have been intrigued by recent media coverage of rubber blocks, the size of chopping boards and bearing the strange name “Tjipetir”, mysteriously washing up on UK and European beaches.

But it was Cornwall beachcomber Tracey Williams who was spurred into action and traced their provenance. Unbeknown to Tracey she was also demonstrating the value of names.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTracing the story of the blocks to a stricken Japanese ship carrying cargo from the Tjipetir estate in Indonesia to Britain, Tracey also discovered the rubber was gutta percha. This latex – produced from a species of the tropical tree family Sapotaceae – played a key role in the development of the telegraph cable network that, for the first time, allowed instant communication across the world.

A little more investigation revealed Tracey was not alone in finding these blocks. Today, her Facebook page is full of pictures showing other Tjipetir block discoverers from Spain to Shetland.

To a plant taxonomist like me, who has worked extensively in Indonesia and is currently researching the family Sapotaceae, the story was fascinating.

However, what was particularly interesting was that it was the name on these blocks that had grabbed everyone’s attention and prompted them to gather, link and share information.

This simple point of reference, the name, reflects the fundamental reason for the existence of research organisations like the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE).

While many people take names for granted and assume that everything has one, it is not necessarily the case for plants: especially plants from the species-rich tropics. Scientists and horticulturists from RBGE spend considerable time undertaking fieldwork and collecting plants around the world for research purposes and it is not unusual for us to return with species that are new to science and requiring to be formally “described”. Indeed, an average of 2000 new species of flowering plants are described each year.

It requires painstaking research to work out what name to give a plant or to confirm that a plant has not already been described and is actually a new species.

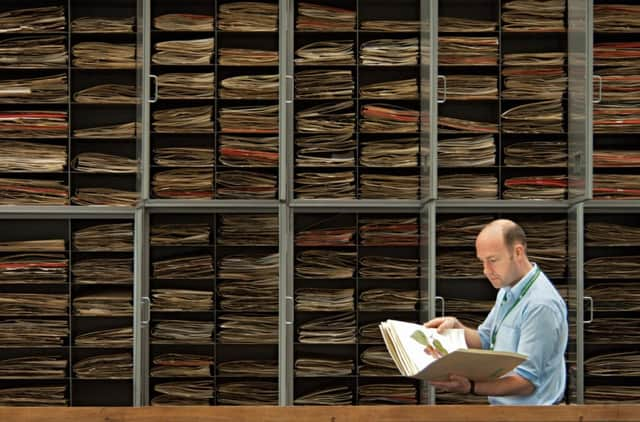

For species-rich groups, a researcher may need to check hundreds of specimens held in preserved plant collections – known as herbaria – around the world and review, in detail, literature that may go back hundreds of years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnly once this has been done can we begin the process of naming and describing a new species.

Unlike local names, which can apply to more than one species, scientific Latin names adhere to a strict code of nomenclature that ensures one solitary name relates to a single species. This means it can be used by anyone anywhere in the world to confidently communicate and share information about that species.

Unfortunately, unlike the Tjipetir blocks, plants don’t conveniently have their names imprinted on them. So, taxonomists need to link new species names to a reference specimen, known as a “type”, and a published description of the species so others can check they are using the name correctly.

These reference specimens are deposited in herbaria and the publications held in botanical libraries such as the one at RBGE.

Back in the 1850s, as the world woke up to the potential uses of gutta percha, nothing was known of its botanical origin. This changed when a specimen collected in Singapore was passed to WJ Hooker, of Kew, who subsequently gave it its name.

That, in turn, allowed others interested in the tree and its products to communicate for the first time without potentially confusing it with other sources of latex.

This information helped the Glasgow-based Dick brothers source the raw materials they needed to make the popular rubber-soled plimsolls still known today as “gutties”. Additionally, it helped companies gather latex – from the single species providing true gutta percha – of the quality needed to provide insulation for deep-sea telegraph cables. What’s more, as early as 1858, it allowed the then Regius Keeper of RBGE, Professor Balfour, to raise concerns about the potential extinction through over-exploitation of this species.

Today, taxonomists routinely incorporate new scientific advances such as DNA sequence data with their herbarium-based research in order to provide the baseline information for biodiversity and conservation research.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs we face the sixth mass extinction event in Earth’s history – this time caused by humans – the valuable information held in our collections is increasingly important in making assessments about threats to different species and informing conservation actions.

If only naming the world’s biodiversity was as easy as stamping “Tjipetir” on a rubber block!

• Dr Peter Wilkie is a tropical plant taxonomist, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh