Understanding Asia is vital for the West

Recent events in Afghanistan and Syria underscore the perilous times we live in. How to evaluate our options? Can we stand by as so many die in the Middle East? Should we negotiate with the Taleban? Where are the lessons in all of this? Who wins, who loses?

These are the dilemmas crystallised in the urgent need to better understand the countries of Asia, from the Gulf in the west to Japan in the east.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAsia offers colossal commercial potential but also seismic fault lines arising from unresolved sectarian and tribal conflicts and arbitrary colonial frontiers.

These make it imperative that whether we are soldiers, policymakers or business people, we need a far deeper knowledge of the peoples of Asia to engage with them more fruitfully.

These were the catalysts that led to the launch of the Asia Scotland Institute (ASI). The Institute’s mission is “to promote awareness, understanding and collaboration between Scotland and Asia to create mutually enriching economic, cultural and educational opportunities”.

We do this by providing access to thought leaders such as Stephen D King, chief economist of HSBC and, on 2 and 3 July, Jim O’Neill, creator of the term BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Awareness, understanding and collaboration have been in short supply in Afghanistan and other “war on terror” battlefields, resulting in a situation where “we really have no answers for how to control the violence”, in the words of Professor Akbar Ahmed, speaking at our latest event, held in conjunction with the Alwaleed Centre for Islamic Studies at Edinburgh University.

The former Pakistani High Commissioner to the UK and Brookings Institution scholar proceeded to dismantle myths exposed by his study: The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam.

From Waziristan to Somalia, Helmand to the Yemen, the hostility directed at the West is emphatically neither a clash of civilisations nor the product of militant Islam, he said.

Instead it is part of a complex struggle between the centre (the all-powerful Drone) and the periphery (the prickly Thistle).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe spoke of Pakistan as “a dire situation of conflict” between the central government and tribal provinces where “a simmering independence movement” is too easily dismissed as foreign meddling. “I heard the exact same thing in 1971 about East Pakistan,” he warned.

Tribal identities underpin everything, he explained, quoting an elder in Waziristan: “I have been a Pashtun for thousands of years, a Muslim for a thousand years, a Pakistani for 65 years”.

This recalls an Afghan proverb oft-quoted by the Taleban taunting its Nato adversaries: “You have the watches, but we have the time.”

Scotland a hopeful example

Ahmed’s plea was for a coming together of civilisations so all groups command respect. Indeed, Scotland has been a hopeful example, he said, of “a people allowed to live in dignity and with a sense of honour”.

His warnings echoed those two weeks earlier of Dr Vanda Felbab-Brown, another Brookings scholar ASI invited to Scotland, who presented her research on state building in Afghanistan in her book Aspiration and Ambivalence. Her prediction of a “triple earthquake” of military, legal and economic breakdown after Nato troops withdraw, expertly summarised by Bill Jamieson in these pages, concluded that many Afghans believe a civil war is inevitable.

Profound misunderstanding of the country, and the population’s needs, led the Allies to “systematically compromise good governance for the sake of military exigencies,” she said, propping up a corrupt regime.

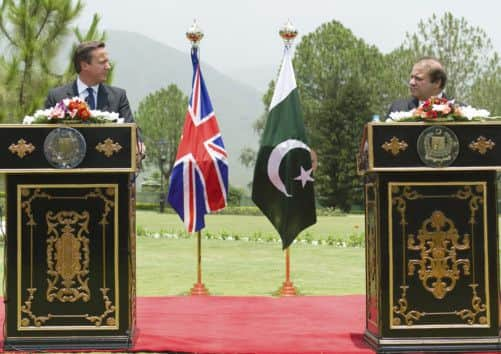

She argued that the West foster the rule of law. Does that sound a little like David Cameron’s plea for a greater sense of reality in dealing with any transition in Syria?

To bring this all back to our work at the institute, knowledge and understanding enable us to comprehend the different cultures and markets of Asia, to place the reasons for conflict in their historical perspective, to place political and economic drivers in their cultural setting, to grasp what it takes to be successful and act accordingly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe need for ASI’s declared mission has never been greater. Scotland must embrace the century of Asia, as our forebears embraced “emerging markets” so influentially in centuries past. Global competition for Asian customers and Asian capital demand it.

“You have the watches but we have the time” may be an Afghan proverb, but it might equally apply to the Asian view of the global economy.

• Roddy Gow is chair and founder of the Asia Scotland Institute www.asiascotlandinstitute.com

SEE ALSO