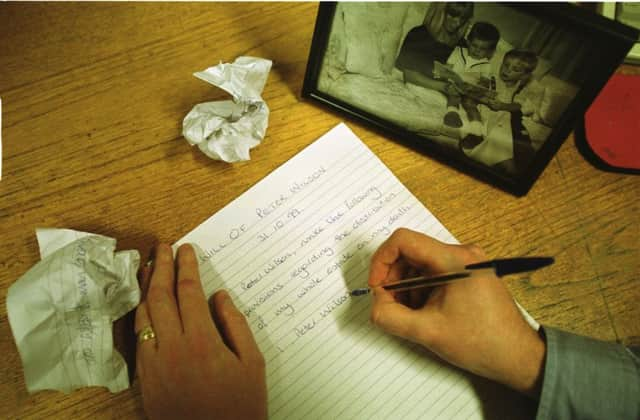

Uncharitable side of wills and Heather Ilott case

CHARITIES have expressed surprise at the decision in the case of Heather Ilott, who sued her mother’s estate and secured an award of over £163,000 despite having been disinherited in her late mother’s will. The result of the court decision is that three charities named in the will receive less than Mrs Ilott’s mother had intended. Some have expressed the fear that this means the end of testamentary freedom – others are simply puzzled how this end result could have been reached.

The case was decided under English law, but the principle – that there are legal limits on what testators are free to do with their estates – applies here. In the Ilott case, this principle arises under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975. In Scotland, the principle arises through the operation of “legal rights” in two main situations. A surviving spouse or civil partner can make a claim for legal rights against the estate of their predeceasing partner; and a surviving child can make a claim for legal rights against the estate of a predeceasing parent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn each case, the amount which can be claimed is either one third or one half of the moveable estate (everything except land and buildings), depending on the relatives left behind by the deceased.

The principle of testamentary freedom is therefore qualified in Scotland by a potential claim for legal rights where a person dies leaving behind a surviving spouse, civil partner or children. The English position also provides for a qualified form of testamentary freedom. In the Ilott case, the relevant part of the 1975 Act is for a child to make a claim for “reasonable financial provision” to be made for him or her from a parent’s estate. The reasonable financial provision is limited to the amount which the claimant ought reasonably to receive for his or her maintenance.

The practical effect is that a charity (or anyone else) named as a residuary beneficiary in a will may not receive the amount they anticipate at the start of an executry. Claims may be made which will redirect assets to otherwise disinherited family members of the deceased, reducing the amount of residue available at the end of the day.

In neither Scotland nor England are these potential claims new. The English law is 40 years old this year, while the Scottish rules on legal rights have been with us for centuries in one form or another (the current Scottish rules are a combination of common law and the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964). The Ilott case is therefore not the beginning of the end of testamentary freedom – the freedom to disinherit certain relatives has been limited for some considerable time.

What should charities make of all this? The Ilott case is a reminder of circumstances in which a will can be successfully challenged by surviving relatives. But another practical point arises. In the Ilott case, much was made of the fact that Mrs Ilott had been estranged from her mother for 26 years and her mother had little connection with the three charities named in her will. Mrs Ilott knew she would be disinherited, so there was no expectation of inheritance on her part. By the same token, the three charities named in the will equally had no expectation of inheritance, since they were not aware of the contents of the will and had no note of Mrs Ilott’s mother within their databases of donors. For the charities, any inheritance from Mrs Ilott’s mother represented an unexpected windfall.

If that is so, would the case have been decided differently if there had been a relationship with the charities during the mother’s lifetime? Some English commentators think so. The advice to charities is to maintain contact with donors to build up an understanding of family circumstances. Meanwhile, the advice to testators is to give clear explanations for the disinheritance of children and to engage with charities to which they wish to leave their estates.

This is all good sense, but it will not particularly help in Scottish cases where legal rights claims do not have any reasonable provision element. Charities with Scottish donors also need to be aware of proposals to extend legal rights claims to land and buildings.

Ultimately, charities must understand claims can arise which may affect their entitlements under wills and situations in which those claims arise may be increasing.

• Gavin McEwan is partner and deputy head of charities at Turcan Connell www.turcanconnell.com