Tiffany Jenkins: ‘Literature is not for you’

Once upon a time I was a member of the Puffin Book Club, the children’s club from Penguin Books. It had a magazine in the early days – the Puffin Post – with puzzles and stories from writers that included Roald Dahl and Alan Garner, and all of its members received a marvellous badge of a puffin that I treasured and still have in my jewellery box.

They were grooming us, of course, for the hard stuff, for the Penguin list for adults, and in the long run for Penguin Classics, for the great books that included the authors Aristotle, Austen, Nabokov and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

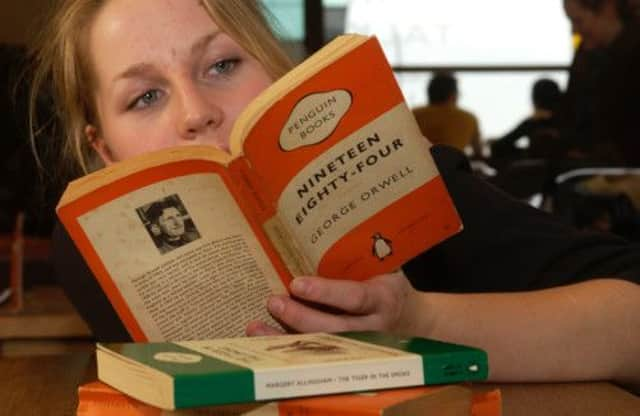

Hide AdThe publishing house shapes what we read. It is a gatekeeper of culture, playing a crucial role in deciding what is great literature. And I have followed their guidance. Not exclusively – I read well beyond their list – but I have been pleased with the orange, blue and green paperback Penguins, as well as the black covered Penguin Classics that I find myself reading again and again but have yet to exhaust.

Well, no more. Penguin have blown it. Today they are publishing the first edition of Morrissey’s autobiography as a Penguin Classic, saying that it is a “Classic in the making”. Now the ramblings of a once popular but peculiar singer will sit alongside Montaigne and Milton. And yet there is no way they are comparable. All the other writers have had to work for this accolade by standing the test of time, but not Morrissey. His autobiography will not be worthy of the title a Classic. Suggesting so insults the achievement of the other writers and us readers.

Get a sense of humour, I was told when I moaned to friends – it’s tongue in cheek, apparently. But it’s not that funny. It’s predictable, and it tells us something important about our cultural gatekeepers. Now they seem to sit around in meetings working out how they can undermine their own role rather than doing what they should be doing – valuing and nurturing culture for us all. Because these kind of flippant, publicity seeking acts are not confined to this one publishing house, this is not just about Penguin. Companies such as these sometimes lose their way, others usually take their place, but not in this case. They are one of many acting recklessly.

Just recently, the National Trust opened the Big Brother house to the public, for a weekend. The National Trust, known for tending to the buildings and landscapes of the great, good and exceptional, such as a Robert Adam country house or a coastal beach walk, was keen to distance itself from this role, and instead fawn over what they think the common people like. The National Trust appeared more enthusiastic about chasing the fading celebrity of a few housemates than preserving important places for posterity.

It was a stunt that was a little behind the times. After all, Big Brother was at the height of its popularity in 2005. But that is often the way when senior managers try to identify something that is hip – they get it wrong and look a bit desperate. They did, however, get a great deal of press attention which is what I assume they wanted. But, in so doing, as with Penguin giving up on the Classics by publishing anything that catches their eye rather than a work of importance, opening the Big Brother house suggests that what the National Trust used to do – value and care for important locations – is no longer central to their purpose.

The trouble with eschewing the role in deciding what is culturally important – be that books or buildings – is that the role of a gatekeeper is a good one, and can be democratic. Prior to the first Penguin Classic there were few readable editions of the great books published for everyone. What came before was primarily aimed at academics and students. That changed in 1946 when EV Rieu – an unknown classicist – suggested to Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, that he publish his translation of Homer’s Odyssey. Rieu had been working on it with his wife Nelly and they thought people might be interested to read it. And they were right, people were interested.

Homer’s Odyssey, the first Penguin Classic, sold three million copies. It was more popular than Big Brother is now – the viewing figures for the last series was, on average, two million. Indeed, the National Trust has a membership that is the envy of every other organisation, reaching about seven million, with around 61,000 volunteers as well as 17 million annual visitors. Many think what the trust does is important, even if certain members of staff seem not to feel the same way.

This is about how cultural gatekeepers see us, the public. Not only do they appear to be losing faith in great books and buildings, bowing instead to the worst kind of cultural relativism, they have lost faith in the public – that we might be interested and capable of expecting more, that we might like to know about great books or buildings. These media-savvy acts are the product of an inverted snobbery which pretends to be for the people, but really says: “Don’t bother with important literature – it’s not for you; don’t bother with significant buildings – they are not for you.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe relationship between cultural gatekeepers and the public was never one in which we were dictated to, it was always more of a two-way engagement than that. Gatekeepers should, on the basis of their expertise, judge the great works, and we should engage with them: disagree, counter-argue, or even agree and affirm. It can and should be a lively dialogue, but it is only possible if we can trust the judgment of such gatekeepers, and if they respect the audience, neither of which appears to be the case today.

“Give a girl an education and introduce her properly into the world,” Jane Austen wrote in Mansfield Park, “and ten to one she has the means of settling well”. Sadly, one publishing house that publishes her books in their Classics list no longer believes in its role in helping us get that education, it is more concerned with venerating the ramblings of old pop stars. It is time to get rid of my Puffin Club badge. I am no longer proud to be a member.