Tiffany Jenkins: Biting the hand that funds art

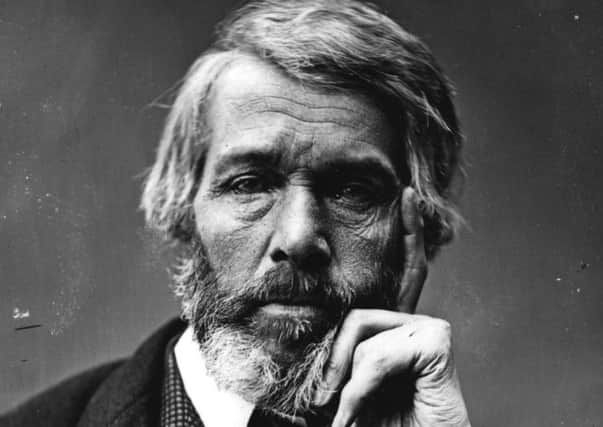

Writing in the 1840s, Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish historian, described the painted portrait as “superior in real instruction to half-a-dozen written ‘Biographies’.” The study of great men, he believed, would be enhanced by seeing their image. Carlyle was living in the time when photography was invented, which would challenge painting as the chosen medium to depict a likeness but never replace it. To this day, a painted portrait is a unique record of the sitter. It does more than show the status and authority of a respectable man, or capture well the dress and wealth of an important lady – it reveals someone’s inner life.

Which is why the exhibition of the BP Portrait Award is such a pleasure to visit. Every year, for the last 35 years, a team of judges select the greatest new portraits from around the world. And every year there is at least one work that stands out, where you can look into the eyes of the person portrayed on the canvas and see who they are. A good painter goes beyond just capturing a resemblance, they grasp the essence of the person with their paintbrush.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were 2,377 entries for the BP Portrait Award this year. The judges whittled them down to 55, including the winner – who gets £30,000 and receives a commission to paint a portrait for the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent collection. Thomas Ganter, a German artist, won the top prize, for Man With A Plaid Blanket. Ganter’s picture is of Karel, a homeless man, and is painted in a manner usually reserved for nobles and saints.

You can go to see the painting of Karel; the exhibition is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery in London and transfers to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in the autumn. The award has been sponsored by BP for 25 years. BP has also invested almost £10 million in partnerships with the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the Royal Opera House and Tate Britain. Closer to home, BP supports the Aberdeen International Youth Festival and the Gray’s School of Art Degree Show. The sums flowing into the cultural sector from BP are so significant it’s fair to say this money keeps our museums and galleries at a world-class standard.

But not for much longer, campaigners hope. There is increasing pressure being placed on arts institutions to drop BP’s sponsorship of the arts. Last week a performance piece that involved 25 artists with oil running down their faces, distributed around the National Portrait Gallery, was staged by the activist group Art Not Oil.

According to the artist Anna Johnson, one of the participants: “The National Portrait Gallery is marketing BP as socially responsible when it is one of three main companies most responsible for climate change. It’s time for public arts institutions to stop being publicity agents for Big Oil.”

It’s not the first stunt activists have pulled. The theatrical group ‘BP or no BP?’ dressed up as Vikings and carried a 15-metre longship, whilst preaching against taking oil money, at the BP-sponsored exhibition ‘Vikings: Life and Legend’ when it was on at the British Museum.

Around the same time, in a letter to a newspaper, campaigners wrote: “Art shouldn’t be used to legitimise the companies that are profiting from the destruction of a safe and habitable climate.” They are silent on where the funds to replace BP’s millions could come from.

Artists and arts institutions have always needed significant sums from the wealthy and from corporations like BP. And they always will. Rather than demonise these funders, we should celebrate their largesse.

The Medici, a prominent banking family, was partly responsible for the flourishing of Renaissance Florence as they funded some the greatest artists that ever lived. Without the support of these power-crazed men, we may not have had the art of Michelangelo, Donatello, Fra Angelico and Leonardo da Vinci.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Tate gallery was founded by the sugar merchant Henry Tate. The red standstone Gothic revival building of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery was only built when John Ritchie Findlay, then owner of The Scotsman, donated tens of thousands of pounds. The current list of sponsors for National Galleries Scotland includes Baillie Gifford, Lloyds Banking Group and Scottish Widows. Art doesn’t come cheap.

Campaigners point out that corporate sponsorship is used to make the companies look better. Of course it is – ‘twas ever thus. The Getty family – the oil tycoons of the 1900s – acquired and displayed antiquities and fine art, leading to the creation of the J Paul Getty Museum in California, in part to convey a positive message about their family during a period of a growing public resentment of the upper classes. Supporting art was a way to show that they were civilised people and public spirited.

It’s not entirely convincing that sponsorship achieves a significant change in the image of a company or a person. Like all companies, BP pursues profit. It is also is in the petroleum business – which is perfectly legitimate, by the way. This won’t change all that much despite spending millions on the arts. But it is clear that cultural riches have been nurtured and cultivated as a consequence of their support.

Ideally, the arts should be – and are – funded by various sources: the state, public groups and individuals, as well as corporations, so they don’t become reliant on one kind. And funding should come with no strings attached; don’t forget that it has been the public-sector funders, not the corporate, that have demanded most of arts institutions over the last 20 years, asking for particular outputs, or that certain audiences attend.

The BP Portrait Award prize money makes a major difference to the artists who win. Painting is not usually financially profitable, even if it is rewarding in other ways. Instead of demanding cultural organisations drop this sponsorship, if we want more portraits like the one of Karel we should say thank you and ask for more money.