The power of a human story can force real change - but care must be taken - Karyn McCluskey

Their stories were heart-breaking as they recalled the door knocks at their homes from journalists offering condolences the day after the tragedy.

The power of the story, the personal narrative, can change Government policy, create a groundswell of opinion and action that changes society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

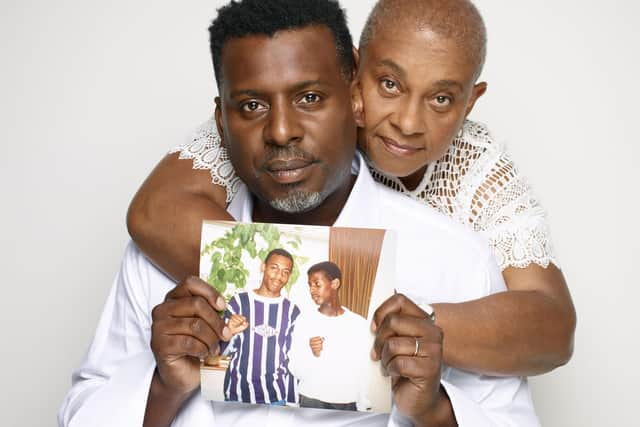

Hide AdThe family of Stephen Lawrence, the parents of the children murdered at Dunblane, and the women who came forward who sparked the MeToo movement have created societal change.

There is a long established phrase which sets the purpose of good journalism: “Comfort the afflicted, afflict the comfortable”. A story has the power to humanise the personal impact of terrible events that seem far away from our own lives. It can bring to life the personality and warmth of lost loved ones and highlight how lives have dramatically changed for those left behind.

Providing a much loved picture of a lost one in happier times to newspapers reporting an event can indeed comfort families in a terrible time. It can also trouble and distress the rest of us and move us to take action. Reporting of events in Ukraine has led to people giving up rooms and houses to people they have never met, but feel a connection with through the power of a story.

In the justice world we’ve also seen the positive impact of stories. From the media campaigns to highlight the need to treat drug addiction as a health problem to those in recovery sharing stories of their journey to bring hope to others.

Those who have been harmed have shared their experience in very public forums, bravely and coherently. Often they take comfort from explaining to professionals and others, how their services did or didn’t meet their needs during the worst experiences of their lives. It has undoubtedly led to change.

It is a complicated and sensitive process for a person who decides to share with strangers the most intimate and painful details of the deepest, darkest events of their lives. But it is their narrative and no one else’s. We have to sit in that discomfort, to be ‘afflicted’ by others’ experience. We have no permission to utilise others’ pain for our own ends, unless the person affected grants us that permission, and their agreement can always be withdrawn. In my own role, people have withdrawn permission for me to share some of their story, sometimes after many years. We have to honour these requests.

Change is important, and we ‘comfort the afflicted’ when their experience leads to change. The parents of the children from Dunblane made this country overwhelmingly safer for others, but the telling must have been excruciatingly painful.

Yet the most dubious use is when we ask those concerned to tell their story – and nothing changes, where there is no clear ask, no contextualising the person’s experience.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe must ensure the voices of the most vulnerable in our society are heard – but on their terms and in a meaningful way. And we need to listen and then act, otherwise nothing changes, and we will comfort no one.

-Karyn McCluskey is chief executive of Community Justice Scotland

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.