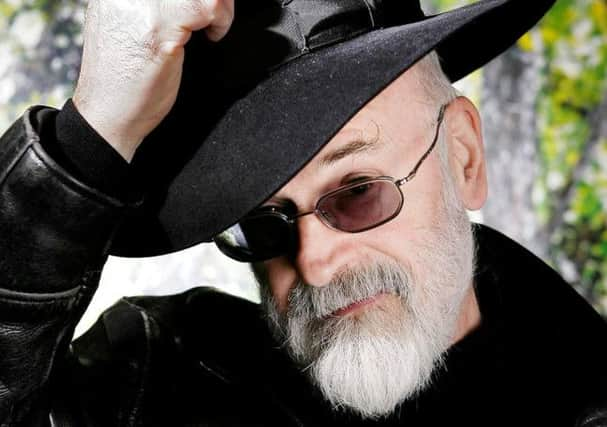

Stuart Kelly: Sir Terry Pratchett, an appreciation

With the sad news of Pratchett’s death, I realise how many of my subsequent critical theoretical opinions have their roots in his books. The fact that Pratchett decided Not To Take Tolkien Seriously seemed thrillingly iconoclastic, and instilled a lifetime’s enjoyment of his precise satire.

With Mort, I came to enjoy typographical innovation – Death here always speaks in small capitals. He would have hated the word, but novels like Wyrd Sisters introduced me to the idea of the metatextual. These were stories about stories, about how language doesn’t describe but shapes reality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwisted fairy tales and sly reworkings of Shakespeare weren’t just the preserve of writers like Anthony Burgess and Angela Carter. They were intrinsic to Pratchett’s art. He nudged reality to the side with surreal brilliance, produced sparkling aphorisms seemingly at will, and with his keen sense of the absurdity of religion he probably made more agnostic and atheists than Sartre and Dawkins combined.

I was privileged to be asked to chair Terry Pratchett when he came to the Edinburgh International Book Festival in 2011, a few years after he revealed that what had been thought to be a mild stroke was actually early onset Alzheimer’s.

Beforehand, I was told that he didn’t want an interview, just an introduction. He arrived, I told him how much I admired his work and he said something like “Good, that’ll make for a good interview”. I was slightly taken aback, yet despite only having minutes to prepare, it seemed as if we could have chatted for twice the time.

When he struggled to find a word, I dug my nails into my palms not to try, gauchely, to supply the word for him. Not just because it was have been rude: so capacious was his imagination, I could never have hoped to predict where his wayward way with words would have gone. There is only one consolation in his death: the opportunity to reacquaint myself with the world he has left to generations of readers.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS