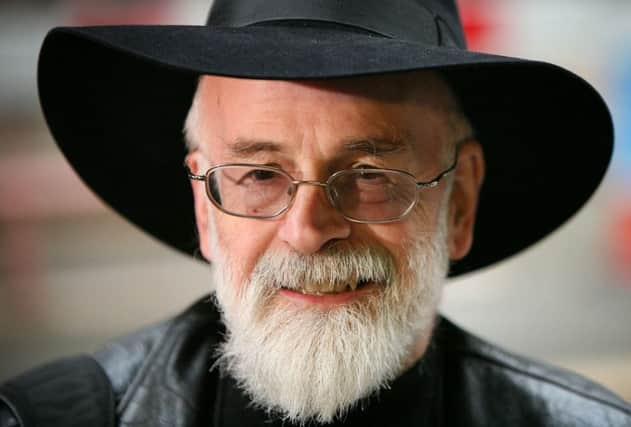

Stephen McGinty: Sir Terry Pratchett - a class act

Today the Central Hotel in Glasgow is a chic boutique hotel with a champagne bar from which patrons can sip a chilled glass of Veuve Clicquot while gazing out at the scintillating beauty of one of Britain’s busiest train station concourses.

The hotel’s guests are affluent couples on weekend breaks and businessmen and women on corporate retreats but in the mid-Eighties a quite different breed of consumers roamed the warren of corridors, frequently armed with plastic axes, illuminated lightsabres and woollen scarfs of such inordinate lengths as to make Tom Baker covetous. For during its shabbier years, when the glamour of guests such as Frank Sinatra or Roy Rogers and his horse, Trigger, had long since faded away, the Central Hotel in Glasgow would play host to science fiction and fantasy conventions such as Albacon and it was here, among the worn upholstery that I first met Terry Pratchett.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI should quickly add a caveat. A phrase such as “I first met Terry Pratchett” might indicate the beginning of a long and fruitful friendship or relationship, the first of many meetings, but as far as I can recall it was also the only time I met Terry Pratchett. Yet he made an impression and, in a way, became my first literary critic.

I would have been 14 or 15 years old at the time and already intent on forging a career as a journalist and he would have been in his first year as a full-time professional novelist.

The Colour of Magic was already out in a Corgi paperback with the captivating cartoon cover by Paul Kidby and racing up the bestseller charts, so I decided to approach him for an interview.

I can’t remember now whether I said it was for a school magazine (we didn’t have one) or a local paper (for which I didn’t write) but I knew that his words would have no firm destination once I had dutifully collected them up.

I approached him after he had clambered down from the stage on which he had been giving a talk. I remember the black leather jacket but I’d be lying if it came accompanied by the black wide-brimmed fedora that would become his signature look.

We found a quiet corner of the hotel, which wasn’t hard as, even when “filled” with fantasy fans, the Central Hotel, like the Tardis, seemed to bend time and space in such a way as to continually expand into empty room after empty room after empty room. Always the amateur professional, I first asked him if he would like anything to drink, aware that I would most probably be unable to be served at the bar, being under age and in any case lacking enough pocket money to afford to keep a successful author sufficiently lubricated. He at first politely declined then, on spying a waitress passing in the far distance, beckoned her over and ordered a coke for myself and a coffee.

I had come suitably prepared with a list of questions, numbered one to ten, on a spiral notepad, and an old Sony tape-recorder, which promptly refused to work. I tried to get it to record. Pratchett tried to get it to record and then we sat it down to sit in rightful shame on the coffee table.

Although I felt quite sick, I smiled, picked up my notepad and pen and attempted to brush it off as a mere inconvenience. Pratchett was impressed: “Ah you do shorthand?” “No,” I replied. “Oh.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad(I would like to say that I left behind technological failure with my teenage years, but a malfunctioning tape recorder has followed me, like the journalistic equivalent of a “black dog” for much of my career. Most recently I travelled to Stirling to interview the historian Neil Oliver, returned, promptly pressed the wrong button on my digital device and wiped the recording. Thankfully Neil Oliver falls into the category of “good guys” and was happy to repeat the process over the phone.)

The next hour or so involved me working stoically through my list of questions and scribbling his answers down while Pratchett spoke exceedingly slowly. At the end of the interview he spent a good 20 minutes explaining why journalism was a fantastic career and one he had left with great reluctance to secure a larger salary as a press officer for the Electricity Board. (With impeccable timing he started shortly after the Three Mile Island incident in America.)

He then wrote his home address on my notepad and said to send him a copy of the finished article or write with any further questions.

Over the next few weeks I dedicated our computing class to typing up the interview and when it was duly finished, printed it out on that thin computing paper with serrated punch-hole sides and posted it off.

Less than a week later I received a reply from Terry Pratchett. I wish I still had it to hand but alas I don’t. I can, though, still remember that he had dutifully re-written almost the entire interview, clarifying his own points and tidying up my own descriptions and introduction.

The line I will always remember was when he wrote: “I hope you don’t mind but I thought I’d crispen up a few of the sentences.”

The kindness and patience Terry Pratchett showed to me as a young aspiring journalist was repeated to thousands more fans over the next 30 years as his comic fantasy novels centred around Discworld would sell over 70 million copies and make him, until the appearance of JK Rowling, Britain’s most successful novelist. He had a close relationship with his readers, who were rewarded with a new book sometimes as frequently as three times per year, such was his prolific nature: even when diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s he continued to dictate new books when he could no longer type. He had a sense of humour, though I got the sense he was disappointed when Rowling slightly stole his thunder, and once attended a convention wearing a T-shirt which read in ever decreasing point size: “Tolkien’s dead. JK Rowling said No. Philip Pullman couldn’t make it. Hi I’m Terry Pratchett.”

In the course of his long writing career he took fantasy, a neglected genre with devoted fans but little critical acclaim, and breathed new life into it through the means of humour. There was no aspect of life such as the law or opera that he couldn’t fold into Discworld. He may have felt that his literary skills were not appreciated because he was a humorous writer but he had fans such as AS Byatt who this week told the Guardian: “His prose was layered: there was a mischievous surface, and a layer of complicated running jokes, and something steely and uncompromising that turned the reader cold from time to time. He was my unlikely hero, and saved me from disaster more than once by making me laugh and making me think.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBoth he and his close friend Neil Gaiman, with whom he wrote the novel Good Omens, constructed literary characters for Death. While Gaiman in his Sandman series cast her as an attractive Goth girl, Pratchett conjured a lugubrious jobsworth who rode a horse called Binky and who liked to end the working day with a curry. He also spoke in block capitals. I like to think that on Thursday afternoon his fans read his own final words when three tweets were published from his official account.

“AT LAST SIR TERRY, WE MUST WALK TOGETHER.”

“Terry took Death’s arm and followed him through the doors and on to the black desert under the endless night.”

“The End.”

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS