Stephen McGinty: Ian Brady - a true touch of evil

When Ian Brady worked as a clerk at Millwards Merchandising, a wholesale chemical distribution company in Gorton, he was quiet, punctual and spent his lunch break reading Mein Kampf, Teach Yourself German and books detailing the atrocities of the Nazis. During his literary tour of all that followed the raising of the swastika, he may have encountered the words of Heinrich Himmler, who when asked to define what he wished the SS to be said: “We must be honest, decent, loyal and comradely to members of our blood and to nobody else.”

He then went on to explain how meaningless were the lives of foreign citizens: “Whether 10,000 Russia females drop dead from exhaustion while building an anti-tank ditch interests me only insofar as the anti-tank ditch gets finished for Germany’s sake.” He ended his speech with a chilling line that captured the utter inconsequence of all the human lives that stood in the way of the goals of the Third Reich: “All else is just soap bubbles.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

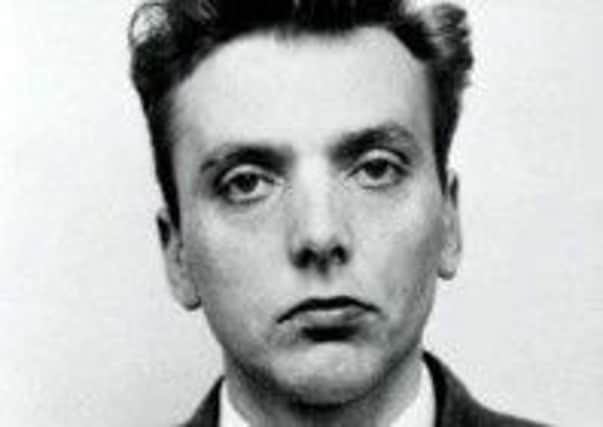

Hide AdThis week,for the first time in 47 years, we listened to Ian Brady, once a pupil at Shawlands Academy and a former tea boy at Harland &Wolf shipyard in Govan, who grew up to murder five young boys and girls with as much regard as a child has bursting soap bubbles. The artist’s illustration was of an old man with a nasal feeding drip (he has been on hunger strike since 1999) who wore heavy glasses. In civil society he would be an OAP, but for many he is the personification of evil. The Moors Murders carried out by Brady and his accomplice Myra Hindley in which she lured in the young victims, asking them for help to find a missing glove up on Saddleworth moor outside Manchester from where they never returned, remain among the most chilling in British criminal history, principally for the involvement of a woman – though Fred and Rose West would attempt to eclipse them.

It is ironic that the death penalty was abolished by parliament while Brady and Hindley were on remand considering the fact that Brady has repeatedly insisted he wishes to be allowed to kill himself. His appearance in public was at a medical health tribunal, where he argued that he should be transferred from the psychiatric hospital where he is currently detained and returned to an ordinary prison.

After an initial 20 years in prison, Brady was moved to Ashworth psychiatric hospital in 1985 after being diagnosed belatedly as a paranoid schizophrenic, a transfer he claimed to have secured through “method acting”.

Carl Jung said that “evil is an intellectual concept, not a true reality”, while Benedict de Spinoza argued that “the knowledge of evil is an inadequate knowledge”. Evil, it seems, is like pornography – at times difficult to define but we know it when we see it and when we see Ian Brady, we see evil.

The Usual Suspects, the cunning and confusing crime film staring Kevin Spacey, popularised a potent phrase: “The greatest trick the Devil ever learned was to convince the world that he didn’t exist.” Largely speaking, we no longer believe in the Devil. Even those who believe in God can’t quite stretch their credibility to encompass the idea of a dark, malevolent sentient force that seeks to corrupt mankind.

So, just as the Devil has been reconfigured over the past few hundred years from absolute fact to childish fiction, so has his Stygian realm of Hell. Where he once ruled supreme and awaited us with sharpened pitchfork should our earthly transgressions warrant eternal damnation, now the fires are out, the demons, once legion, have been dispatched and now theologians argue that what awaits the unrepentant sinner is eternity outside the presence of God. A heavenly party to which there is no invite.

Yet “evil” is a concept that even the most secular society is reluctant to discard, in spite of its previous religious connotations. When we think of someone as evil, we imbue them with a dark power. They frighten us, and we have every right to be frightened given the behaviour and actions they are capable of and are actively willing to carry out.

In a strange way, by branding someone as evil we elevate them from the rest of mankind, the plinth maybe black marble, not white, but they are still raised up, not deliberately, we may not wish this to be the outcome, we may wish instead to bury them, but that is not how it works out, they are not banished from sight, but come into clearer view.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is 50 years since the political philosopher Hannah Arendt coined one of the most important terms of the 20th century. When asked by the New Yorker magazine to cover the trial in Jerusalem of Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, she chose a term to capture this bespectacled human cog in the atrocity machine and it was the “banality of evil”.

At the time the combination of those three words caused outrage, thousands of letters of complaint poured into the magazine’s offices and Arendt lost a number of friends. Less than 20 years after the end of the Second World War, the world wanted to see a monster, not a man and certainly not to have to grapple with the idea that evil, that squat, toxic and difficult little word could ever become in anyway ordinary.

But Arendt performed an important service by coining the term and it was to leak some of the intoxicating power out of the word and the acts it covers. It helped society to move from the largely medieval concept of evil, which was wrapped up in the figure of Lucifer, the Prince of Darkness and the image of an empowered figure unwilling to adhere to the conventions of society. As Lucifer declared in Paradise Lost, “Non servium” – “I will not serve”.

After Arendt’s collected articles were published as Eichmann in Jerusalem, she had an epistolary argument with Gershom Sholam, a scholar of Jewish mysticism, in which she wrote that she did not believe that evil was profound in a traditional sense, but that it was “shallow” and “very deadly and capable of tremendous destruction, like a fungus”. The image of evil, not as swirly black mist, but as lethal fungal spores is attractive.

So, where does Ian Brady fit into this redefinition of evil? His acts cannot slip under the canvas of “the banality of evil”. They were not carried out like a corporate or governmental edict, but were fuelled by a perverse and homicidal obsession. As Gautama Siddharta, the Buddha, said, the root of evil is desire. Brady said this week that, in sexually assaulting and murdering five children and teenagers, he sought an “existential experience”. Is this the truth or has half a century of access to prison libraries allowed him to smear a veneer of intellectual inquiry over his base motives, thus allowing him to distance himself from other, dimmer serial killers?

When Brady was sentenced to life imprisonment, the judge, Justice Atkinson, said he was “wicked beyond belief”, with no possibility of being reformed. Although both statements are undoubtedly correct, while in the mid-20th century “wicked” was good enough, now in the 21st century what constitutes “wicked” is being slowly teased apart through brain imaging, DNA studies and the expanding field of psycho-criminology. The psychology of evil is currently both on the couch and under the microscope.

In another 47 years, Brady, who is now 75, will be long dead, but the dangerous cocktail of ingredients that constituted his lethal profile will have been analysed, the genes that made him quick-tempered and susceptible to violence will be identified, but evil itself will never be isolated and eradicated.

I remember asking a colleague if he thought that evil exists and he replied that not only did it exist, but also that a quick glance around the world provided plenty of evidence that it was thriving.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIan Brady has now shuffled back to his locked hospital ward and, hopefully, the next time he dominates the headlines it will be for his unmourned death. Yet, he is a reminder that as long as man is walking the earth, evil will follow like a shadow.