Scottish independence: how would the judiciary and state be separated?

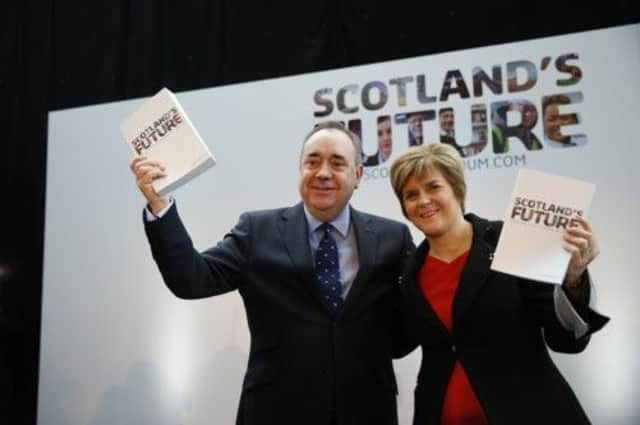

The white paper – Scotland’s Future: Your guide to an independent Scotland – contains myriad proposals on both sides of the line: advocating a new constitutional framework alongside a manifesto of specific policy commitments. In some respects, it’s an understandable approach: putting flesh on the bones of the stark question of statehood by illustrating the practical matters that, it is said, could be dealt with differently if Scotland became independent.

Given, though, that the referendum is not a vote for or against a particular government or its policies, it is the proposed institutional framework and the vision of Scotland’s place in the world which can be said to be of most significance. This is effectively the framework which enables the creation of a new standalone country and at first blush most of the key boxes are ticked. The “guide” confirms and expands on positions already adopted by the Scottish Government. Some are broadly within the unilateral control of a new Scottish state; others require the cooperation of the rest of the United Kingdom (rUK), the European Union and/or the wider international community.

‘Constitutional platform’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo far as domestic arrangements are concerned, a new Scottish state would come into being with a minimal “constitutional platform” setting out the essential constitutional and administrative arrangements needed to establish Scotland as an independent country.

The Scottish Government then intends that, following any Yes vote, the UK and Scottish parliaments would agree on a transfer of power to enable Holyrood to formally enact independence for Scotland and also allow the Scottish Parliament to begin to legislate in all those areas currently reserved to Westminster.

During the transitional period between a Yes vote and actual independence, the Scottish Parliament would exercise these newly transferred powers to create a Supreme Court for Scotland (no more than the removal of the UK Supreme Court’s jurisdiction and the transfer of its power to the existing Inner House of the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary – courts which have in any event always styled themselves as “the Supreme Courts of Scotland”).

This proposal affirms the crucial importance of a superior court to uphold the rule of law – something obviously critical to all citizens, businesses and other parties wishing to protect rights and property in a new state.

Furthermore, the parliament would put in place laws defining citizenship of the new Scottish state; provide for continuity of existing law; and further entrench the European Convention on Human Rights.

It is also proposed that the current devolved Scottish Parliament would impose on the post-independence Scottish Parliament a legal obligation to establish a constitutional convention to prepare a written constitution after independence.

While there seems no doubt about the political will to establish such a convention in the event of independence, there are questions over whether such a legal obligation could bind the new parliament of an independent Scotland.

More generally, the Scottish Government is fully committed to Scotland having a written constitution. Much is said in the Guide about such a written constitution being a reflection of the “sovereignty of the people” rather than the sovereignty of legislators, but there is little discussion about the importance of an independent and robust judiciary willing, where appropriate, to determine constitutional disputes in favour of those whose rights may be infringed by elected politicians. That transfer of power to the courts would, of course, be a key consequence of a move to a written constitution and one which has been little debated so far.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe content of the new constitution would be determined by “the people” as expressed through a constitutional convention, but the Scottish Government has a list of its own substantive priorities it would wish to see debated by that convention – including provisions on equality of opportunity, entitlement to public services and a minimum standard of living, protection of the environment and controls on the use of military force. There is also reference to constitutional protection for local government in Scotland.

On external relations, the Scottish Government’s position is quite clear, but the reaction of other parties (principally the UK government and the EU) would be crucial to the achievement of independence on the terms proposed in the Guide.

Currency

On currency, there is an unambiguous declaration that Scotland “will” retain the pound – and there is of course no means by which an independent Scotland could be prevented from using sterling. However, it is when the Guide discusses formal monetary union with rUK (which would require the consent of the rUK government and parliament) that matters become a little more opaque: the recommendations of the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Commission at times are presented as statements of future fact.

So far as membership of the EU is concerned, there is something of a softer line and a clear recognition of the need for negotiations on the fact and terms of Scotland’s membership. It is fair comment (and, disappointingly for a Scots lawyer, the only Latin in the Guide) that “the Scottish situation is sui generis” (unique), with no specific provision in the EU treaties for part of an existing member state becoming independent but seeking to maintain membership of the EU. That is only one of many reasons to conclude that the question of EU membership (and indeed participation in the euro and in the Schengen agreement) is one to which there is no clear legal answer.

It is, though, like all the other questions thrown up by the Guide, a matter on which all manner of opinions will be expressed over the next nine months.

• Christine O’Neill is chairman, Brodies LLP www.brodies.com