Private education is an investment

When I returned to Scotland in 2014, the independent sector was still recovering from the inevitable consequences of the longest period of recession since the Great Depression.

But Independent Schools Coulcil (ISC) figures published earlier this month, based on their January census, show the sector to be growing once again. What’s more, pupil numbers are the highest they have been since records began.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt would be easy to put this down entirely to improved economic conditions; but recent headlines about the UK experiencing deflation are premature. Temporary negative growth in the rate of inflation actually does little to affect the pound in your pocket: people are simply not that much better off. So if demand for private schooling is less elastic than imagined, why the sudden change in trend?

Regional variations may help toward a clearer understanding of the picture. England and Wales have seen greater increases in pupil numbers than Scotland, which may have something to do with the pace of educational change taking place in the state-sector south of the Border. When I left England last year, one of the deciding factors in my decision to relocate was Michael Gove’s policies for education in England. With Academy Schools and Free Schools springing up to blaze a trail in uncharted territory, parents are not willing to leave their child’s education to chance. Similarly, in Wales, independent school numbers rose by a staggering 4.7 per cent just one year after teachers’ unions warned of knee-jerk initiatives being implemented in the absence of any longer-term vision. So whilst there are many inferences to be made from independent school admissions rising in Scotland by just a third of the UK average, it is likely that the Curriculum for Excellence – conceived over time, and through consultation – has been a definite factor in parental choice. At its core, the new curriculum in Scotland recognises precisely those aspects of educational development already at the centre of independent school provisions. A commitment to developing successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors sounds very similar to the basis of curriculum planning in independent schools. What a new curriculum can’t provide, however, is financial independence, smaller class sizes, supervised study, and greater opportunities for co-curricular development. Only independent schools can make this pledge.

In any case, an argument can be made to the effect that state schools with comparable student populations offer the same advantages as independent schools. But this is to miss the point. The majority of independent schools are no more selective than sixth form colleges; ISC pupils come from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds and the value of means-tested bursaries has risen by 31 per cent since 2011. Yet students in independents schools are still three times more likely to gain A and A* grades at A-level than their state-educated peers. In my own specialist area of independent girls’ education, the figures are even more stark: only one in 20 girls taking A-levels study at Girls’ School Association (GSA) schools; yet one in four of the A* grades awarded in STEM subjects goes to them.

Also, the impact of independent education cannot be ignored: 33 per cent of the new parliamentarians sworn in earlier this month attended independent schools.

Whilst this is surely grist to the mill for egalitarian reformists, it indubitably shows the level of advantage conferred by a private school education. Not just on fee-paying students, either.

With 93 per cent of ISC schools partnering their state counterparts – sharing facilities, expertise and resources – the trickle-down benefits of increased admissions are to be welcomed.

So growth in numbers of pupils attending independent schools is good news for the tacit recognition of excellence that it indicates. Demand has increased in spite of economic conditions; parents are likely to be swayed by the stability and quality of private education in a turbulent educational environment; true independence – in terms of finance, resourcing and provision – continues to safeguard students’ fundamental needs; and, in spite of a more varied intake than ever before, results continue to improve.

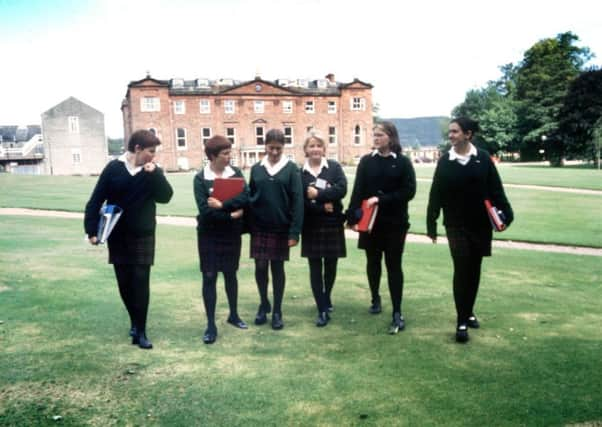

• Dorothy MacGinty, headmistress, Kilgraston School www.kilgraston.com

SEE ALSO