Plan to make decision making clearer

This week, nine organisations, including the National Trust for Scotland, John Muir Trust and RSPB Scotland, signed an open letter to the Scottish Government. It stated that “Public trust in the planning process around major infrastructure developments is at an all-time low. And it’s not just about wind farms; a snapshot of letters pages and online media on any given day reveals angst and suspicion stemming from the sacrifice of areas of wild land, natural heritage, historic landscapes and greenbelt to commercial priorities.”

The organisations went on to state that “at a time when community empowerment is supposed to be in the ascendant, it is ironic to see the honest concerns expressed by local communities, and those united by the desire to conserve our most important natural and cultural assets, swept aside in an unequal battle with powerful commercial interests. As has recently been observed, even the Scottish Government itself has been shown to disregard its expert advisors. This situation cannot continue and it is in everyone’s interests to find a way forward.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe signatories called for the planning system to be revisited and some form of independent arbitration arrangement to be established to review controversial planning applications that may affect communities and landscapes.

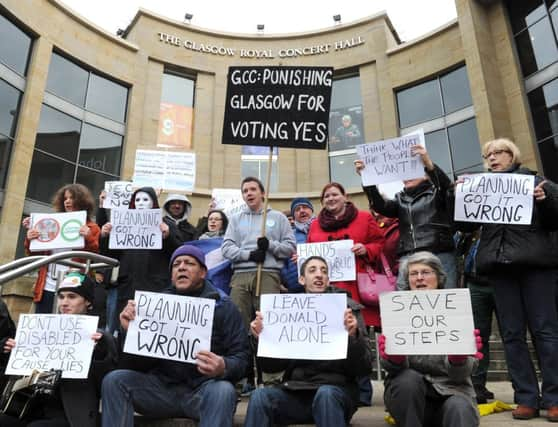

There was an interesting confluence of events following release of the letter: on the same day, in this newspaper, Lesley Riddoch argued that “Scotland needs to become a participatory, community focused democracy” and Martyn McLaughlin observed how, despite a petition signed by 14,000, Glasgow’s planners granted permission for demolition of the public space at the Royal Concert Hall’s steps.

On the following day, the Convener of the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) reacted to the open letter, arguing that, “Scotland’s planning system has undergone major reform in recent years and … is held with high regard across the UK… I do not recognise the contention that ‘public confidence in the planning system is at an all-time low’. This does not chime with the messages I hear from across Scotland through communities and developers.”

I want to make the point that Scotland has been well-served by regulation of land through the formal town and country planning system. In too many local authorities, planning is a Cinderella service. Nevertheless, the default position is one of approval. The question is not, “Is this proposal good enough to approve, but is it so bad as to justify a refusal”. The same mindset seems to apply to decisions that are in the gift of Scottish ministers, which encompass many large-scale applications affecting land-use.

We know many people are deeply worried by what they see as the industrialisation of the landscape. They seek assurances that, in trying to meet the challenges of climate change and ensuring the vitality of our economy, we are not destroying the very places that Scotland needs to cherish and preserve.

This is not just about major wind farm developments. NTS undertook a major survey of public and membership opinion and found that industrial development, pylons and neglect were of as much concern as turbines. Some 72 per cent of the people surveyed felt they had “no influence” in response to the question: “Do you feel you are able to influence how your local landscapes are managed?’ It was also found that only 16 per cent in the least wealthy groups felt they had some influence over the planning system, compared to 46 per cent of the wealthiest.

The RTPI may well be right in asserting that recent reforms to the planning system offer improvements, but misconstrue the points made. If there is insufficient trust in the system, because it is perceived as being too one-sided, it does not matter how good it is in theory as no-one has confidence in practice.

Neither were the signatories arguing for an “unelected quango” to have “a veto on planning decisions” – it is understood public objections are not reasons in themselves to reject applications. The point was that there should be a fair and transparent system of arbitration if there are reasonable indications that decisions rested on incomplete evidence or where due process had not been followed, as has been alleged in relation to two major wind energy projects where the Government is said to have ignored its own advisors. “Justice should not only be done; it must also be seen to be done.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was not an argument for removing the Scottish Government from the planning process, nor for “special interests” to have undue sway, but to ensure that all interested parties have exactly the same rights and remedies.

At the moment, the only recourse ordinary citizens have to challenge apparently faulty planning decisions, be they local or ministerial, is to spend £50-£100,000 taking the matter to court. This is hardly fair and democratic: developers with their deep, often publicly subsidised, pockets can afford to obtain the best advocacy money can buy. If there was a fair, accessible system of adjudication, this would strengthen public confidence in otherwise unpalatable planning decisions: it certainly could not be diminished further.

• Terry Levinthal is the Director of Conservation and Projects for the National Trust for Scotland