Peter Ross: Pause before we disturb dust of the dead

I remember holding it, can still feel it almost; and I remember thinking that I had no right to do so. A tooth, a human canine, that had last chewed food more than 4,000 years ago. I was ten and had found this tooth, trowelled it up in a quarry near Blair Drummond while helping my grandfather uncover a Bronze Age cist.

He was a coachbuilder and keen amateur archaeologist, a weekend Indiana Jones who preferred to combine socks with sandals rather than hat with whip. He had heard about this burial in the pub. A quarryman had partially exposed the grave with his digger. Unnerved by the sight, he downed tools and, soon after, pints. That evening, as my grandfather listened, the whole story, including the location, came tumbling out. So that’s how I ended up bringing the tooth into class, its smooth dry curve cushioned on the soft flesh of my palm, to be marvelled at by the teacher. It was the summer of 1984, Frankie was saying Relax, and my head was full of bones and stones.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI wrote about the excavation, clanking out the details on a manual typewriter for inclusion in Discovery And Excavation In Scotland, the archaeology journal, where it duly appeared, rewritten to include decorous references to “human skeletal remains” rather than callow poetic musings about how strange it is to hold someone else’s teeth in your hand. Still, it was my first byline and had the effect of encouraging me towards journalism rather than continuing towards the hitherto intended life as an archaeologist.

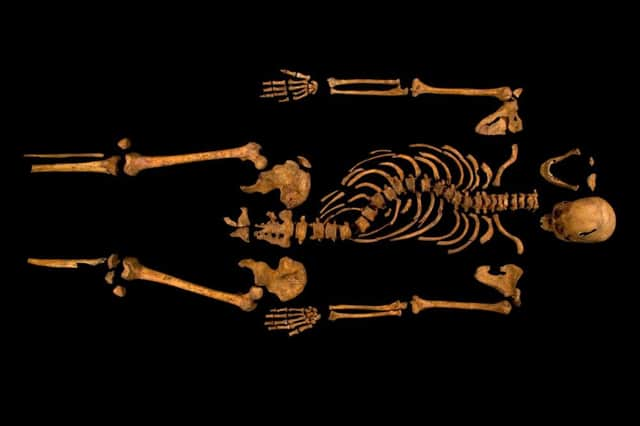

This all came back to me on Tuesday when it was announced they had dug up Cervantes. The remains of the great Spanish writer, who died in 1616, were removed from the sullen earth beneath the crypt of a convent in Madrid. The announcement of this discovery comes just a few days before the controversial reinterment of Richard III, found in a car park in 2012, and due to be buried next Thursday in Leicester Cathedral, much to the displeasure of the good people of Yorkshire – not least my wife – who feel that the last Plantagenet would much prefer to spend eternity in the land of the white rose.

There is, undeniably, something exciting about the discovery of the famous and infamous dead. A jinked spine, a fragment of a skull that once contained the plot of Don Quixote – these are sights that bring legends to life. But as we thrill to look upon their bones, should we not feel something more akin to shame? After all, these people were laid to rest in the expectation that it would be final. Prayers would have been said over the bodies. We tell ourselves that high-minded curiosity is what motivates us as we grasp the spade (and there is no question that scientists and historians can learn a huge amount from analysis of ancient remains) but are voyeurism and arrogance the true driving forces? There are no near relations to speak for these people – or for the 3,000 Bedlam skeletons dug up to make way for Crossrail, or the 400 medieval Leithers disinterred to clear a path for trams that never came – and so, without advocates, they are fair game and we root them out like truffles.

What is the difference between exhumation and excavation? Nothing but a few passing years. The idea of our loved ones being disturbed and moved elsewhere is often distressing. In my own extended family, quite recently, there was a great deal of upset caused when a relation who died in the late 1980s was moved to a different cemetery so that, among other reasons, he could be closer to where the family now lived and more convenient to visit. This was disturbing for some. The belief that our loved ones are at peace is held instinctively by many of us, regardless of whether or not we have religious faith, and it gives comfort. It is surprising, then, that what we find hard to bear when it is done to our immediate families, we accept as quite natural when done in the name of research or progress. Time makes hypocrites of us all.

I am not saying let us have a moratorium on archaeology; let us sink every bog body back into its bog, and shake the National Museum of Scotland till the skulls come rattling down Candlemaker Row and into Greyfriars Kirkyard. Certainly not. But I’d prefer us not be so quick to assume we have the right to turn bodies into specimens and spectacles.

There is a charming old phrase in Scots law that human remains have the “right of sepulchre” and a wonderfully resonant 1824 judgment: “No-one has a right to break up the ground of interment to the remotest period of time. There the dust must for ever remain.”

I like that. It should be scratched into the metal maw of every excavator. Of course we must have more roads, more railways, more space in which to build homes and shops, but the idea that we have to disturb graves in order to do so should at least give us uneasy pause.

After all, we are running out of burial space in Scotland and the rest of the UK. The solution, according to the Institute of Cemetery and Crematorium Management, is to reuse abandoned graves a minimum of 75 years after the last body was laid to rest. It might, before too long, be you and I who find ourselves playing Yorick.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRecently, I took my sons, age seven and 11, to the British Museum. We admired the Lewis Chessmen, the Elgin Marbles, and all the other stuff that shouldn’t be there, and then we had a look at Lindow Man. He was killed in the north-west of England some time between 2BC and AD119 and discovered in 1984, the same year as my grandfather found that grave in the Blair Drummond dirt. Preserved, stained and flattened by the peat in which he lay, Lindow Man appears bark-skinned, mulch-boned, autumn made flesh. The children were upset, but not by his frightening looks, I don’t think; rather by an instinct that here was a face not meant to be seen, much less kept behind glass and photographed by tourists.

Like an old tooth in a boy’s palm, it just felt wrong. So I took their hands and we moved on quickly to the gift shop.