Peter Jones: Free to offend and to be offended

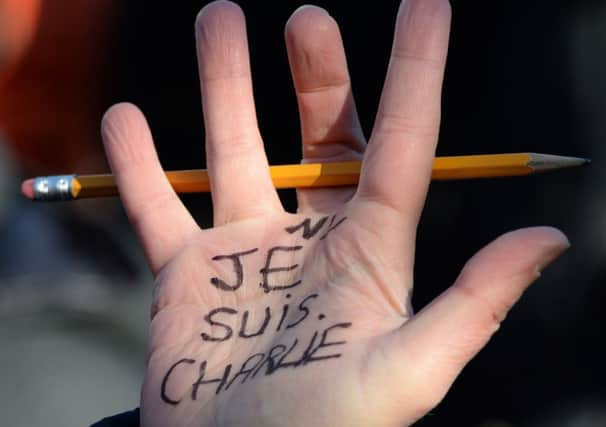

AM I Charlie? I would like to think so, that I stand alongside the millions who took to the streets on Sunday to defy the terrorists who wish to murder in order to destroy the rights of liberty and free speech. But am I really, or am I just paying lip service?

Many other journalists are asking themselves the same question and coming to uncomfortable conclusions – that we do not measure up to the standards set by the writers and cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo. They knew that what they published put their lives and those close to them at risk. They carried on, and, despite armed police guards, they still paid the ultimate, terrible, price.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo I salute them, and I mourn them. But I am left with the awful, empty, feeling that I have little of their courage.

Much of what follows has been said by others, but I make no apology for repeating their thoughts because they all lead to the same point – that last week’s dreadful horror in Paris has exposed a moral question to which there appears to be no universally clear answer. When exercising the right to speak, write, and draw freely in the knowledge that it will offend some, when is that right defensible and when is it not?

Of course, even when the exercise of that right causes gross offence, not just against sensibilities but against the laws of the land, that does not confer a right on the offended to threaten and kill. Nothing can ever do that.

But mention of “the laws of the land” brings into sight the fact that we do curtail the right to free speech that offends. We do not allow free speech that incites illegal activity such as public disorder that may end up with damage and injury to property and persons. That is well accepted.

We do not allow free speech that encourages discrimination against persons because of their gender, race, skin colour, or religious belief. While there is an argument that such speech should be allowed in order to permit exposure of its absurdities, which I have some sympathy with, it is nevertheless accepted that prohibiting incitement to discrimination is an acceptable limit on free speech.

So the right to free speech is qualified. That is because to leave it unqualified would erode other rights – the rights to live peacefully and uninjured, to enjoy property, and to have equal opportunities to employment and societal freedoms regardless of race, colour, and creed.

But other aspects of the law have gone further, notably Scotland’s recent law to curb offensive behaviour at football matches. I agree that the sectarian chanting and singing on terraces is revolting and should be stamped out. But I am not at all sure that the law is the right way to do it.

That is because it is unclear to me what important freedoms are being threatened by sectarian chanting. If I was of a particular faith and I heard chanting which suggested my faith was a sick perversion, I would be offended, but has my freedom to exercise that faith, to attend football matches, or have any of my other social and economic freedoms been undermined and put under threat?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI find it hard to work out why that might be so. I suppose the argument is that to permit sectarian chanting risks the acceptance of sectarian attitudes which might become embedded in certain sections of society, thus threatening those other freedoms which are more valued.

The evidence, however, strongly argues that the opposite has happened – that despite sectarian behaviour amongst certain football audiences being still strong, actual sectarianism in Scottish life has faded away.

The existence of this law, however, raises another troubling point. The Charlie Hebdo staff were killed, it seems, because they had dared to publish a cartoon depicting the prophet of Islam, Mohammed. Amongst Muslims, this is blasphemy. To Islamist fanatics, it merits the blasphemers’ death.

That is utterly abhorrent, but nonetheless it is an appalling reality we have to confront. The greater freedom we wish to protect is the right of people to draw cartoons of Mohammed to make some point or other. But what if Scotland was playing a team at Hampden which had, say, a Muslim goalkeeper, and the Tartan Army thought it was funny to wave a banner depicting the prophet haplessly letting in goals?

Most people might think it was harmless, but under the football law it could be regarded as offensive and illegal. Why could there be a case for arresting and prosecuting the banner-waving fans, but not the editor of a newspaper which published precisely the same cartoon? Both the fans and the editor would be risking provoking the same violent reaction from extremists, but the fans could be criminals and the editor courageous. Why would that be right?

I use this example despite its improbability solely to make the point that trying to legislatively control offensive behaviour is strewn with hazard.

The possibility of both events occurring is remote, not least because the media in this country self-censors. Journalists are reluctant to publish anything which might offend the religious, not for fear of offending sensibilities, but for fear that they, their staff if they have any, and their families might be attacked by some crazed Godnik.

The fear of offence causing nasty consequences, even if they are relatively mild, is not confined to concerns about Islamists. Imagine a cartoon which depicted men dressed as Nazi storm-troopers invading Arab-looking homes and brutally evicting the occupants. Imagine also that, instead of swastikas, their armbands showed the Star of David.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWould that be a legitimate comment on the treatment of Palestinians by the Israeli government, or would it be vile anti-semitism?

The bottom line here is that, to live in a society where you are free to pursue any religious belief you choose is also to live in the knowledge that other people may be offensive about that religion. The two rights are inseparable and to suppress one of those rights is to suppress the other.

But in our modern society, we have blurred the moral distinctions involved, giving little clarity to journalists. It also means, I am ashamed to say, that while I may say “Je suis Charlie”, in my actions I am not.