Patterns emerge from unpredictable picture

My book Referendums and Ethnic Conflict began on the back of an envelope on a UN-chartered plane headed for Khartoum, Sudan in 2009. A colleague had suggested that I publish a book on referendums and independence, now that I’d finished advising the UN on the subject.

There have been many different referendums on independence. This is one of the problems for the social scientist who deals with generalisations. It is difficult to compare the Latvian referendum in 1991 with the plebiscite in French Guinea in 1958. And when you add the cases of Québec 1980 and Southern Sudan 2011, the picture becomes blurred, messy and downright confusing. And yet, there are some patterns that repeat themselves.

The following snippets are extracts from the book:

IGNORING A YES VOTE

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdONE surprising finding is that outcomes of referendums occasionally have been ignored or have given rise to completely different outcomes.

On 8 April 1933, the premier and Nationalist Sir James Mitchell’s government organised a referendum on independence in Western Australia. The mineral-rich state did not want to share resources with Canberra. The referendum was held alongside the state parliamentary election. Mitchell campaigned in favour of secession while the Labor party had campaigned against breaking with the Federation: 68 per cent of the 237,198 voters voted in favour of independence. Only the mining areas, populated by keen federalists, voted against the move. But on the same date, the Nationalists were voted out of office. The fact that Mitchell had lost the election effectively killed the proposal. The state sent a half-hearted petition to the Westminster Parliament requesting independence. It got nowhere. The petition was ruled out of order. Convention dictated that it be made by the Commonwealth of Australia and not by the individual state.

The pattern repeated itself 9,117 miles away 12 years later on the Faroe Islands, north of Shetland. When Denmark was occupied by the Germans in April 1940, the Fólkaflokkurin (a separatist party) immediately called for independence. This was rejected by the other parties who had a majority of the seats in the assembly (Løgtingið). Throughout the Second World War the Faroe Islands were under British protection, but internally the Islands were governed by the Prefect (Amtmand) and the Løgtingið. At this time the Islands were governed by a provisional law which allowed the assembly to pass legislation. During the war the Islands thrived economically by selling fish to the Scots and, partly as a result, support for independence grew.

This support led to the Fólkaflokkurin being one seat short of a majority in the elections of 1943.

At end of the Second World War both Copenhagen and Tórshavn agreed that the status quo ante was not viable. The Danes offered the Faroese a limited measure of home rule – known as ‘the Danish proposal’ to replace the pre-war status. This was seen as insufficient by the Faroese government. Fólkaflokkurin, as the largest party in the Løgtingið, decided to hold a referendum on the issue. To the surprise of everyone, not least the separatists, a narrow majority – 50.7 per cent – supported independence. The Danish Prime Minister Knud Kristensen initially said that he accepted the result. But then he rather conveniently “fell ill”, or so it was said. The acting Danish Prime Minister Thorkild Kristensen asked the King to dissolve the Løgtingið. In the subsequent election, the Unionist parties won a comfortable majority.

This majority negotiated a far-reaching agreement between Copenhagen and Tórshavn. According to this, the Faroe Islands were granted Home Rule in most areas apart from Defence and Foreign Affairs but kept its two members of the Danish Parliament. Effectively the Faeroese were granted what is now known as “Devo Max”.

The result of the vote in 1946 was not independence, although a small majority had voted for this. But it is arguably the case that the devolution-max that resulted from the negotiations was closer to the preferences of a majority of the voters. The referendum in 1946 thus paved the way for a compromise that most voters, at the time at least, wanted. Whether the same could happen in Scotland is an open question. History doesn’t always repeat itself.

THE END OF THE HONEYMOON

SO WHEN do you win a referendum? When you have a popular policy? Yes, up to a point, but there is more to it than that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmerican political scientist VO Key once wrote, that “To govern is to antagonize”. This is a problem in referendums. Governing is never cost-free. All governments break promises, fail to deliver and enact unpopular laws. The more years a government has been in office the lower the Yes vote in referendums. When we analyse the statistical data from referendums in Europe we find that the support for a policy falls by 0.5 per cent for every year the government has been in office.

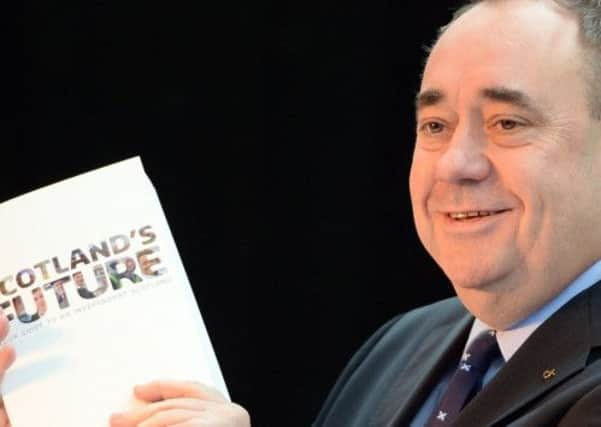

This doesn’t sound like a lot but if the two sides are neck and neck every percentage point counts. Maybe Alex Salmond should have opted for a much earlier referendum. Only time will tell.

• Matt Qvortrup’s book Referendums and Ethnic Conflict is published by University of Pennsylvania Press. Advance copies of the book can be ordered online at www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/15197.html