Michael Sheridan: Should the punishment fit the crime's consequences?

The position was formerly fairly clear in Scots law. It was the criminality which attracted punishment although a sentence may take into account other elements such as public protection. The consequences of the crime, such as its impact upon a victim, were not generally reflected in the sentence. which addressed the wrongdoing of the perpetrator rather than the satisfaction – or even the vengeance – of the victim. The civil law rather than the criminal law provides remedies for those persons who have suffered loss or damage as a result of the wrongful actions of other persons. Where the wrongdoer has no resources, as is often the case, then the Criminal Injuries Compensation scheme may be engaged.

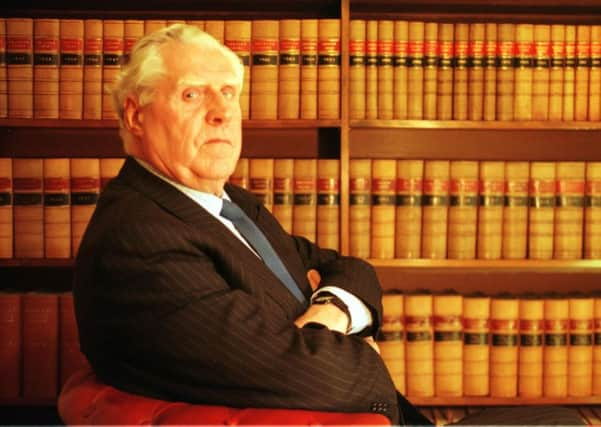

That, I believe, was generally the position throughout the UK until 1989 when the late, and most distinguished, Lord McCluskey took what was then regarded as an almost revolutionary step in inviting the victim of an attempted murder and serious sexual assault to advise the court as to her feelings while the court was considering sentence. One difficulty was that the perpetrator had been shown to have been an otherwise pleasant individual who had apparently acted completely out of character. The case, of course, had its own peculiar facts and circumstances and Lord McCluskey had previously consulted other sources before finding that he wished to hear directly from the victim. At that time, such an enquiry in Scotland was regarded as unprecedented and was compared with foreign jurisdictions in which, for example, it was possible for the family of a victim to have a capital sentence commuted on payment of what was sometimes known as “blood money”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, before many years had passed, Lord McCluskey’s approach had become the norm and there is now legislation in place which provides victims with an opportunity to submit to the court a written statement as to the impact upon them of the crime for which sentence is due to be passed. In England there are provisions which enable members of the public to challenge sentences which they deem to be too lenient.

This legislation, however, does not compel the judges to take into account the impact upon the victim of the crime and the question posed above appears to remain open and subject to interpretation from one court to another.

In one recent road traffic case, an offender was convicted of a relatively minor contravention which, however, had the tragic consequence of ending the life of one victim and causing injuries to three others. In imposing a 12-month disqualification from driving along with the community service order, the judge explained that, while he could not ignore the tragic consequences of the offence, he had to take into account the level of criminality, which was a momentary lack of attention. Thus, the sentence did not appear to reflect the particular consequences of the offence.

In another case, however, this time in England, a person who had been convicted of serious offences of sexual assaults upon children was told that the fact that the victims were Asian was an aggravating feature that justified a more severe sentence than was normal for these offences.

This was because of the particular shame that was suffered within the community as a result of such assaults. When that decision was challenged at London’s Criminal Appeal Court on the grounds that the sentence had been unfairly inflated by reference to the victim impact, the appeal was turned down.

The Appeal Court said the judge “was having particular regard to the harm caused to the victims by the offending” and that the “harm was aggravated by the impact on the victims and their families within this particular community.”

We appear to have entered an era of uncertainty as to what is the basis for the imposition of punishment for criminal offending.

One reason for the advent of this uncertainty may be the emergence of social media. Previously, and ongoing in the minds of at least some Scottish judges, however, the imposition of sentences in the criminal court was governed by the rule of law, rather than by victim impact or public speculation.

Michael Sheridan is Secretary of the Scottish Law Agents’ Society