Michael Kelly: Indifference to independence

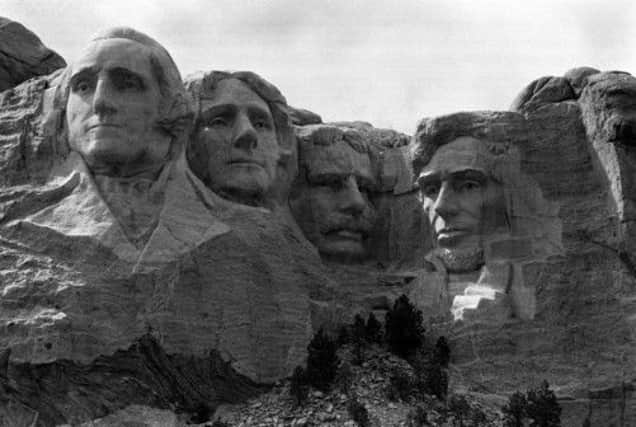

LOOKING out at the sun setting on the Mount Rushmore memorial to four presidents, it is difficult to prevent one’s thoughts turning to the enduring political issues of human and civil rights that Americans believe are embodied in these men.

Earlier, in Philadelphia, those musings focused on independence and the fight for freedom that began there. To many 18th-century North American colonists, revolution may have been about unjust taxation and a lack of control over government. But the Founding Fathers who sat together in what Americans now call Independence Hall had a higher purpose in mind. Contributing to the revolutionary ideas spread earlier by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and contemporaneously by Thomas Paine, they planned not just a breakaway from Great Britain but a whole new form of government. They dared to dream of creating a republic with – in the words of a later president who is remembered on Mount Rushmore, Abraham Lincoln – “government of the people, by the people, for the people”. This challenge to the traditional autocratic regimes that dominated the civilised world’s nations was treasonable, and not just in the colonies. In Scotland, Thomas Muir was sentenced to transportation for similar seditious thought, as talk of political reform was savagely suppressed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMen such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin brought their considerable intellects not simply to the development of these political ideals. They met together to design templates which they determined to use to turn these challenging political theories into practice. Jefferson’s genius drafted the Declaration of Independence, but such was the fertility of the debate that it was amended 87 times before finally being adopted. The signatories, however, were fully aware of the repercussions their act would cause. Moreover, they were acutely conscious that it would make them traitors in the eyes of the Crown, that war would follow and that they would forfeit their lives if that war were lost. That prospect neither deterred their adherence to the principle of inalienable rights nor their preparedness to die for it.

Their commitment led to the modern world’s first republic – though the French with their bloody version of 1789 might dispute that. A constitution was established which swept away arbitrary government by monarchy and oligarchy, basing government on the rule of law. They did not get everything right: that constitution tolerated slavery, women were ignored, capital punishment is still legal. In one of the biggest mistakes, it was quickly amended to allow citizens to bear arms.

The question of how America got from the Liberty Bell to Guantanamo is an issue for another day. The point is, in those days well over 200 years ago, an issue of substance was fiercely debated. Not everyone agreed with secession. The issue was examined by the important men of the day and, as far as communication then allowed, by the public. But the leaders were determined that nothing constitutionally would ever be the same again.

In the middle of our own separation debate, we seek the serious discussion, the analysis of the choices facing us, the passion and the outrage. Why is it all negative and mud-slinging? We have people of intellect. We have political philosophers in our universities. We have committed and fairly able politicians. We have superb means of communication. What is lacking is an issue of substance. In Britain we have developed a mature democracy. Our political system addresses most of the demands of our citizens. Independence does not represent a great leap forward. It is mere tinkering. And nationalism has had its day. It was a 19th and early 20th-century way of thinking. The nation state is on the wane. To unionists there is no grand idea that can better this. To promise more would be to mislead. More devolved power might or might not make a marginal difference to how we are governed. That’s it.

Nationalists have exactly the same problem. They can offer nothing in the way of dramatic, obvious change for the better in the way the Founding Fathers could. More control over expenditure and taxation may or may not lead to better decisions. But people are not going to notice it in their monthly pay. So indifferent are Scots to independence that those advocating it spend more time emphasising the things that will not change rather than conjuring up an inspiring vision. Advocating change while promising continuity is hardly a rallying cry. There is no great difference in what either side offers, no principle involved. To claim otherwise is to pretend.

The independence argument is bluntly irrelevant to the great political issues of the day. A politically united Europe, ensuring the emergence of China does not disrupt world stability, living with Islam, the tackling of corruption and poverty throughout Africa, devising mechanisms to make democracy more representative without handing power to lynch mobs – these are issues worthy of rapt attention, fierce debate and concerted action. By comparison, our irrelevant petty domestic spat is a sideshow on the political stage.

Political ideas have had world-shattering effects. The innovations of the Founding Fathers, adopted bloodily by France, swept western states. The false but deeply held ideology fuelled by dictatorial atrocities in Russia briefly threatened those beliefs but ended in the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

Nothing fundamental will occur after September 2014. All the rhetoric in the world will not change that. The paucity of the independence proposal is emphasised by the latest crazy proposal from the advocates of “Yes”. Hiring novelists or poets to jazz up the text of Salmond’s declaration of independence will not disguise the emptiness of the proposal. Independence as a political jewel has had its day and the world has moved on. That’s why there is really nothing much to debate.