Michael Fry: SNP makes mockery of constitution

For a movement grown up out of a yearning for freedom, the SNP has become a strangely authoritarian outfit.

This is especially noticeable in its irrepressible urge for the micro-management of Scots’ lives: no smoking, no drinking, no singing of sectarian songs, indeed no boisterous behaviour of any kind from football fans. Or, if we look for positive rather than negative measures, then a new snooping bureaucracy of guardians for our children and a new national police force working on the assumption that it can stamp out the oldest profession. In poetic terms we would have to say this was the party of Holy Willie rather than of Robert Burns.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere, to be sure, the SNP does represent one deep strand in Scottish society. But the nation has always brought forth a Robert Burns to match every Holy Willie, to generate as much creative anarchy as control freakery. It has always been more untidy, precarious and provisional than other nations, than its southern neighbour especially, which has lived under centralised authority for a millennium.

That can be defined as the great weakness of Scotland yet also as the great strength, letting the nation respond to every historical circumstance. So it keeps going when others – the Kingdom of Bavaria, the Republic of Venice – have vanished. But what interests me is the future prospect if the British framework that has contained and constrained the inner demons should be lifted after September 18. I wonder especially because the prevailing assumption in Scottish government seems to be that it is in principle omnipotent. Presented with any problem, it need only pass a law at Holyrood and the problem is solved. Hence the proliferation of detailed central regulation on anything from the height of domestic hedges to the actual titles of the songs that are to be deemed sectarian. That way madness lies. We need a new, more general framework to contain and constrain the inner demons, a system of categories and rules rather than of detailed mention for every last jot and tittle of an offence.

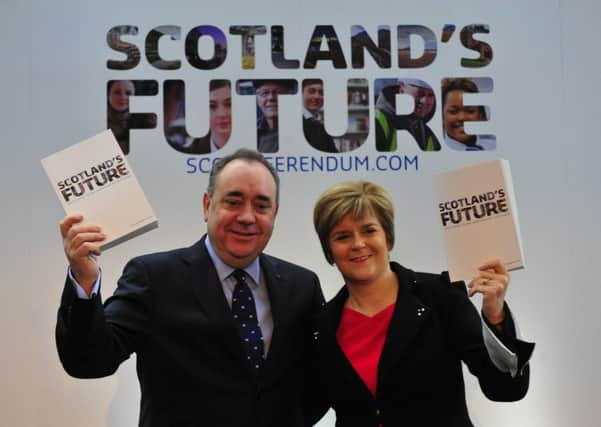

Luckily we have the example of other nations that have gone through the same tensions of winning freedom and have finally stilled them by granting themselves a constitution. From the American constitution drawn up by James Madison in 1787 to the amended constitution of the Republic of Georgia, the work of Lado Gurgenidze in 2010, these are documents telling you a great deal about what a nation is and what it can become. We already know an independent Scotland would be a constitutional state and not, like the United Kingdom, an unconstitutional state subject to the arbitrary rule of the Crown-in-Parliament (otherwise known as politicians). And it is good to hear from Nicola Sturgeon, Deputy First Minister, that some kind of draft for the Scottish constitution will be put out this summer, even before the referendum.

But the constitutional ideas of the Scottish Government, so far as we can perceive them as of now, are less reassuring. Alex Salmond has himself intervened to say “what I have in mind are constitutional provisions that go beyond those touchstone rights to embrace fundamental human concerns, the key economic, social and environmental needs of every citizen and the responsibilities of state and citizen towards each other.”

What the First Minister means by touchstone rights are the protections of fundamental freedoms in the European Convention on Human Rights. Among the things he means by provision beyond those fundamentals are, to give his own examples, a right to free education, a right to vital social services, an end to child poverty.

Anybody who has ever studied politics or philosophy will recognise here the basic distinction between “freedom from” and “freedom to”, a distinction that pervades the modern history of democratic nations. On one side of politics people demand freedom from the power of the state. On the other side of politics they demand that the power of the state should guarantee them freedoms they might not otherwise enjoy. The usual way to reconcile the positions is a system of checks and balances.

It is good to see Scotland starting to traverse the path all other constitutional states have followed. I would just point out that the Scottish Government, while saying one thing, is doing another. At the same time as the high-minded principles are being enunciated, the Justice Secretary, Kenny MacAskill is clobbering the judiciary because it will not assent to his abolition of the hallowed rule of corroboration in Scots law. It is safe to say that under no other constitutional order in the world (except England’s) could he get away with this. He is in fact following the English principle otherwise rejected by his government and his nation: the principle of the absolute sovereignty of Parliament which lies at the heart of the UK’s constitutional decay and possible death.