Mary O’Neill: Dictionaries writ large with Scots

Why is it that so many of the UK’s best-known dictionaries and reference works have Scottish roots? Encyclopaedia Britannica, Chambers Dictionary, and Collins English Dictionary all have their origins in Scottish firms, and Collins dictionaries continue to be produced in Glasgow. The multi-volume Oxford English Dictionary was overseen in the early 20th century by Borders man James Murray, and later by Dundee-born William Craigie, also the editor of the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue.

Scottish connections can even be found in the dictionary of notorious Scot-baiter Samuel Johnson: the principal London publisher of the Dictionary of the English Language of 1755 was William Strahan from Edinburgh, and five of its six amanuenses were Scots.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

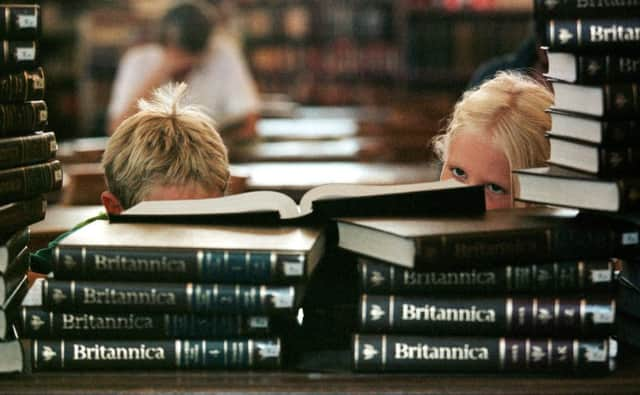

Hide AdWe can conjecture that the Scottish Enlightenment had a bearing on Scotland’s publishing. This is nowhere more apparent than in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, first published in Edinburgh in 1768, and intended as a reference work to reflect the breadth of learning of the time. Britannica has long been in American hands, but its thistle emblem remains a testament to its Scottish birthplace.

In its wake came works that would establish their Scottish publishing houses as field leaders, not just in Britain but worldwide. The Glasgow firm Blackie & Son produced influential titles such as The Imperial Dictionary (1847) and The Imperial Atlas of Modern Geography (1859).

Back in Edinburgh, W & R Chambers published the Cyclopaedia of English Literature in 1844, a work that became a standard history of English literature into the 20th century. This was followed by Chambers’s Encyclopaedia, and in 1867 by Chambers’s Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. By the end of the 19th century,

W & R Chambers was one of the biggest English-language publishers in the world, and Chambers (latterly Chambers Harrap), continued to publish from its Edinburgh base until 2009. Founders William and Robert Chambers started out with an objective of being “publisher for the people”, bringing affordable educational literature to as wide a readership as possible. It was a goal that had come to characterise Scottish publishing.

The vision of “creating knowledge for all” motivated another Scottish publisher who would become closely linked with dictionaries and reference books. William Collins set up his firm in Glasgow in 1819, originally producing prayer books and religious pamphlets. By the time steam presses were introduced to it in the 1850s, the company was producing books on a massive scale, and its output included dictionaries, atlases, and the Bible.

When looking at the history of reference publishing in Scotland, one cannot help but observe its connections, not just with education, but with religion too. The predominant Calvinist ethos may well have encouraged the desire and ability to read among as wide a section of the populace as possible. Indeed, a series of education Acts in the 17th century had brought about a network of “parish schools”, supervised by the Church of Scotland. These schools were believed to have led to a higher literacy rate in Scotland than in England – though the belief is no longer widely held.

Yet the proliferation of reference works by Scots in the 18th century, particularly those concerned with the English language, may also have been motivated by a desire that Scots should be literate in the “correct” way. As Scots strove for betterment in post-Union Britain, and anglicisation became part of that process, lists of Scotticisms were being produced in order to help Scots replace their native usages.

One only has to read the introduction to Scots schoolmaster James Buchanan’s 1757 work on correct pronunciation to understand the social implications of a Scottish accent and vocabulary: “The people of North Britain seem, in general, to be almost at as great a loss for proper accent and just pronunciation as foreigners … I therefore beg leave to recommend this book to … all teachers of youth in that part of the United Kingdom; by a proper application to which, they may in a short time pronounce as properly and as intelligibly as if they had been born and bred in London”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Burn, an English teacher from Glasgow, published A Pronouncing Dictionary of the English Language in 1777, also with the hope that it would “enable one to read or deliver written language with so much propriety, as not to offend even an Englishman of the most delicate ear”. Clearly, Scotland’s linguistic observers and educators had become skilled in their appropriation and cultivation of English. Perhaps, then, it should come as no surprise that so many Scottish lexicographers are involved in compiling and publishing English dictionaries today.

In more recent times, the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, the fruit of a 44-year project, was masterminded at the University of Glasgow; and this year Collins has produced new editions of two of its most prestigious titles, The Times Atlas of the World and Collins English Dictionary, from its Glasgow base.

Perhaps we in Scotland flatter ourselves to think we are intellectually and culturally inclined – for whatever reasons – to bring learning to as wide an audience as possible. But it can be an inspiring notion, and one which publishing history seems to bear out.

• Mary O’Neill is project managing editor in Collins Language, who worked on the just-published 12th edition of Collins English Dictionary