Martyn McLaughlin: A lost Orson Welles masterpiece

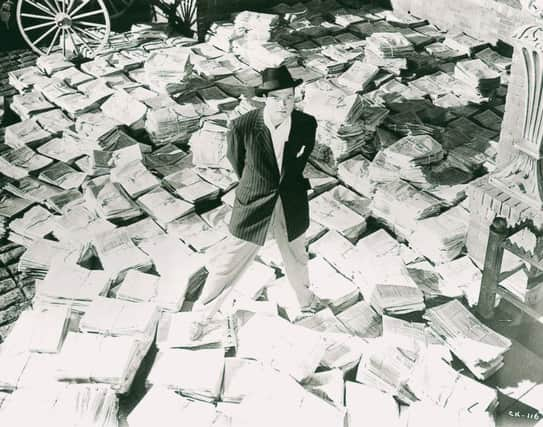

In the twilight of his career, when he veered from one project to the next like a great ocean liner in search of a berth, one film anchored Orson Welles’ restless imagination. The Other Side of the Wind has been described as the greatest movie never seen. It is a skittish verdict borne out of a seductive mythology rather than critical acumen, yet the account of the film’s genesis, stunted growth and unresolved fate constitutes a spellbinding epilogue to a storied life.

Tomorrow marks a century since George Orson Welles was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where the winds whipping in from Lake Michigan carried apocryphal tales of the boy wonder far and wide. One of the least trustworthy recalls Welles at eighteen months, startling a visiting orthopaedist by peering from his crib and - sans dummy - remarking: “The desire to take medicine is one of the greatest features which distinguish men from animals.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLegend and lore swaddled Welles into adulthood and beyond. Three decades after his death, they are a persistent bane for those who seek to divorce fact from fiction and fathom an extraordinarily prodigious figure who, for all his wayward whims, cast the mould from which modern cinema still takes its design.

The centenary of Welles’ birth was to have shed the odd shaft of light on the shadows of his oeuvre. Nearly 40 years after principal photography came to an end on The Other Side of the Wind, hopes were high that the feature, regarded as a companion piece to Citizen Kane, would emerge from obscurity, with talk of a premiere at Cannes. It is an aspiration that will pass unfulfilled. Cinéastes point to any number of lost or incomplete Welles projects that stir the imagination. We can but wonder what might have become of Don Quixote, a lifelong labour, or his vision for The Magnificent Ambersons, were it not for the injudicious work of his editors at RKO. In all, Welles died with around 19 projects unfinished, but The Other Side of the Wind is the most tantalising and elusive of them all.

When shooting began in 1970 - the first film he had directed in Hollywood since 1957’s Touch of Evil - the film’s convoluted, self-referential concept seemed curiously innate to American cinema’s New Wave. It focuses on the return from self-imposed exile of Jake Hannaford, an ageing Hemingwayesque director played by John Huston, intent on making a triumph of his lascivious, low-budget comeback.

Spanning a solitary evening, the modish film within a film takes place at Hannaford’s 70th birthday party, the venue bustling with crews, journalists and actors. Those captured holding cameras were themselves recording the commotion; in the fashion of cinéma vérité, Welles used every source, assembling an elliptic agglomerate of 35mm, 16mm, and Super 8 film shot in colour and black and white alongside still photography.

Occasionally, Huston consulted a slipshod script rewritten nightly by Welles, only to find a succession of speeches. His hooded eyes would catch the director’s attention. “Orson, what page are we on?” “Well, John, what the hell difference does it make?” came the contrabass reply. Huston, shifting his stooping gait closer, insisted: “I want to know how drunk I’m supposed to be.”

The film’s seven year-long production was as piecemeal as its premise as Welles, his rotating cast and a skeleton crew crisscrossed friends’ houses and vacant lots in the Arizonian hinterlands. He financed it in part through cameos, voiceover work and much-derided commercial work; one day, the increasingly corpulent bon vivant would advocate sherry, the next Findus frozen fish fingers. “They hire me when they want a little class,” he reflected. “I chip off a little of myself each time.”

But it was Welles’ wooing of other investors that would lead the film into an abyss from which it has yet to return. A primary backer was Les Films De L’Astrophore, an Iranian firm helmed by Medhi Bouscheri, brother-in-law to the Shah. Though hundreds of thousands were embezzled by a producer, Bouscheri continued to funnel funds to Welles, in return demanding greater control over the edit. After 1979’s revolution, a labyrinthine arrangement became altogether impenetrable.

Six years later, on 10 October 1985, Welles was found slumped over a typewriter at his Californian home, a keystroke away from redemption. The Other Side of the Wind, intended as a three hour meditation on mythmaking, alpha male braggadocio and the very medium he had defined, had spawned a mere 40 minutes of completed footage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the years since, 1,083 reels of negatives comprising 10 hours of raw footage have languished in a Parisian warehouse. Peter Bogdanovich, a close friend of the auteur who also starred in the film, hopes to bring form to the chaos, having secured Welles’ copious notes and negotiated a fragile détente between L’Astrophore and the other rights holders: Oja Kodar, his longtime companion; and Beatrice Welles, his daughter and sole heir.

But a discomfiting silence around the project rivals Charles Foster Kane’s Rosebud for pained intrigue. It remains unclear if the final credits will ever roll. Whether they should at all makes for a legitimate debate. Allowing others, even those Welles trusted, to wrest control of post-production might yield a composite, a curio, but little more.

Yet this seems to me a price worth paying for a new Orson Welles film. His is a life which, for all its achievements, has been distorted through the prism of unanswered questions and unfulfilled glories. A giant of a man is forever a step behind the legend which eclipsed him. We are consumed by his failures, but only because he helped redefine what we understood by success.

Before his death, Huston spoke fondly of his time on The Other Side of the Wind. It was, he said, “an adventure shared by desperate men that finally came to nothing”. That, surely, is a film worth seeing.