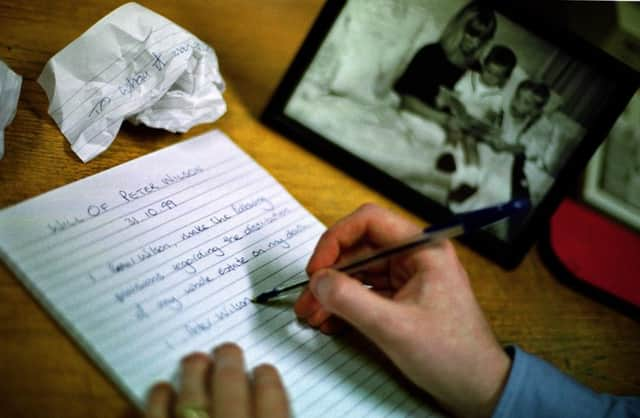

Making a will can protect your partner

MOST of us are aware of the importance of making a will, but are perhaps still guilty of delaying the finalisation of this. However, a recent case in the Court of Session has highlighted yet again how important it is to have wills in place to ensure clarity and certainty after the demise of a loved one.

Mr M, who died on 10 August, 2007, was from Ireland, but had lived most of his life in Scotland. He had lived with his partner Ms K, for 22 years prior to his death, but they had never married.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr M had not made a will. His estate comprised two bank accounts, one in Scotland and one in Ireland, and a house in Ireland worth around €200,000 in January 2009. Mr M regarded the house as family property but had never lived there himself.

In Scotland, where a partner or cohabitee dies without leaving a will, their partner has six months to make a claim to the Sheriff Court for a share of their late partner’s net intestate estate.

To make the claim, the couple must have been cohabiting immediately before the death. The decision as to the amount awarded is made by the Sheriff in terms of section 29 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006, which lays out the rights of a partner’s claim on the estate, taking into account the length of the period the couple were living together, the nature of their relationship during that period, and the extent of any financial arrangements which existed during that time.

The sheriff decided that Ms K should receive a capital sum of £5,502 on the basis that her claim was a discretionary one, rather than a right of succession. He decided the property in Ireland was part of the net intestate estate, and could therefore be taken into account when considering the application.

Ms K was not satisfied with this award and appealed to the Sheriff Principal. Mr M’s children were also unhappy with the sheriff’s award and also appealed, arguing that the award should not have been made at all.

On appeal, the Sheriff Principal decided that Mr M’s net intestate estate should not include the Irish property and that accordingly, no capital sum should be paid to Ms K.

Ms K then appealed to the Court of Session. She argued that section 29 was not part of the Scots law of succession, but an independent and novel statutory scheme, requiring the sheriff to have applied a general “principle of fairness”.

The Inner House of the Court of Session decided that Section 29 was indeed a part of the Scots law of succession, and that it was unlikely that the Scottish Parliament intended to establish a special regime independent of other legal categories. It did not accept that a general principle of fairness should have been applied, did not accept that the Irish property should be included, and upheld the Sheriff Principal’s decision that no capital sum be awarded.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, the Appeal Court was critical of the wording of section 29 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006.

The court observed that the legislation gave neither an indication of the underlying principles, which should be applied, nor any guidance to the court, simply stating that it was to have regard to any matter, which it might consider “appropriate”.

The court drew a comparison between the Scottish legislation and the provisions of the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependents) Act 1975, which applies in England and Wales in such circumstances. Those provisions provide a detailed list of matters, which the court should consider when an application is made by certain family members, including cohabitants, where no provision is made for them in the will.

The court made it clear that the precise principle, which ought to be adopted, was a matter of policy, which should be considered by the Scottish Parliament. It was not the responsibility of the court to decide which principles should apply.

However, until any new legislation is introduced, partners who are in the same position as Ms K are left in the unfortunate position of not knowing exactly what rights they might have.

If they are considering an application to the court, it will be very difficult for them to predict accurately what the outcome of their application is likely to be.

The case highlights not only the need for partners to make a will to prevent the need for a Section 29 application, but also to ensure they have made a will in any country outside Scotland, where further property might be held.

• Dianne Paterson is a partner in Russel + Aitken LLP www.russelaitken.com