Lori Anderson: The death of the signature

Saddam Hussain’s resembled a cobra balancing on a see-saw. John Hancock’s was so big because he wanted King George III to see it first before anyone else’s. John F. Kennedy’s was as promiscuous in style as the president was in person, while my own is simple, lazy, involves two letters hugging each other tight and is a forger’s dream, for they could literally scribble it in their sleep. The signature, that personal mark, a flourished sketch in ink on paper, is fading away under the bright white light of technological change and now the National Archives in Washington wish to mark its eventual erasure.

A new exhibition recently opened in America entitled Marking the Mark which gathered together hundreds of examples of signatures and examined the squiggles’ role in history. The oldest known signature is to be found on a Sumerian clay tablet which dates back to 3100 BC when a scribe called Gar.Ama left his mark – which resembled, to the modern mind, a shopping basket levitating above a toilet (or maybe he just had really bad handwriting). Since then our personal mark has evolved over the millennium from waxed royal seals to inky signatures and in America none is more famous than that of John Hancock, the governor of Massachusetts, who signed the Declaration of Independence in a hand so large it was later said that he wished the King to read it without aid of glasses. In America today, a “John Hancock” is still slang for a signature.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

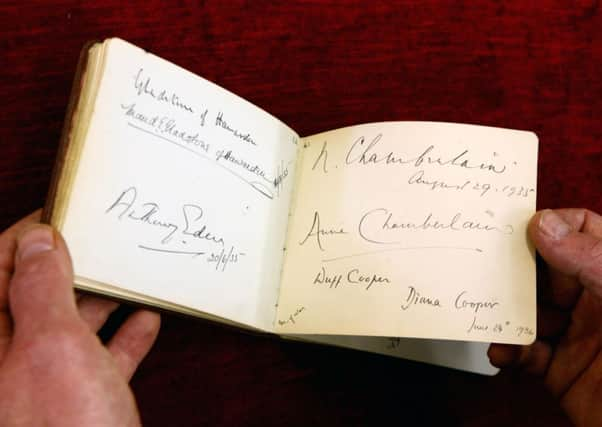

Hide AdThe exhibition has some fascinating exhibits of celebrated signatures. Michael Jackson’s is appended to a patent application for the high ankle support shoes he developed in order to perform, without aid of stunt wires, the deep lean dance move in the video for Smooth Criminal. Fidel Castro’s is attached to a letter he wrote when just 12 years old in which he congratulated President Roosevelt on his re-election then asked if he would send him a $10 bill. (How history might have changed had Roosevelt bothered to reply.)

There are also signatures that are not signatures. Members of the Hopi tribe each drew a personal picture as their mark on a letter to the US Federal Government asking for land rights, while the difference between a public autograph and a private signature is demonstrated most clearly by Frank Sinatra, who signed his letter to President George H W Bush applauding his bill to make the burning of the American flag a criminal offence “Francis Albert”.

The most chilling exhibit is the marriage certificate of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun, which not only has the signature’s of the bride and groom but as witnesses Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann.

Technology has in the past aided the signature but now it threatens to replace it. The auto pen, in which the fluid movements of the author’s hand was replicated by countless other pens was first put into practice by politicians and government appointees. During the Second World War George C. Marshall, the chief of staff of the U.S. Army, signed a personal letter of condolence to the family of each fallen soldier but within weeks the number of dead outstripped the limited time he had available and so assistants were trained to forge his signature. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 resulted in thousands of deaths of US soldiers, not the tens of thousands that Marshall had to contend with but still Donald Rumsfeld used an auto-pen to sign multiple copies of condolence letters, until the practice was revealed, and he sheepishly reverted to signing each letter personally.

The demise of the signature can be traced to 2000 when President Clinton used an e-card to sign his name digitally to legislation that made online documents legally binding. As he said: “Just imagine if this was available 224 years ago, the Founding Fathers wouldn’t have had to come all the way to Philadelphia to sign the Declaration of Independence, they could have emailed their John Hancock in.” New technology also makes it possible for Barack Obama to sign the fiscal cliff bill in Washington while 4,800 miles away in Hawaii, and for the late Norman Mailer to sign books for fans at the Edinburgh Book Festival without leaving New York. To me these long-distance signatures may have appeared genuine but they also seemed fainter and less personal, like an echo heard down a long corridor.

As Jennifer Johnson, the chief curator of the exhibition, said: “As a historian I think it’s sad, but I think it is inevitable. I do think we are losing a little bit of uniqueness.” I do too. There is little question that the signature is being erased from public life. The cheque has been cancelled. The personal letter no longer posted. When the man from DHL arrives on my doorstep he no longer clutches a clipboard and proffers a biro but holds a squat plastic box with a clear glass screen and hands me a plastic wand and while I may scrawl an approximation of my signature it is instantly transformed into a pixilated impression locked beneath the glass screen. There is no leaky ink stain or smudge. It is my signature but it really isn’t.

We are in the dying moments of a human practice that has gone on for 10,000 years. If the life span of the human signature was itself a signature, then all the letters have been looped together, the ascenders have spiralled up, the descenders have swooped down and the fine ink pen is a millisecond from its final rest. Sadly, the signature has signed off.