Let’s stop being complicit in stealing democracy from people of Malawi

This event rivalled even the Cabinet Crisis of 1964 when some ministers, including a Scot, rebelled against Dr Hastings Banda for ideological reasons about relations with China versus the West and economic ones, over salaries and hospital charges. Then, Scotland chose to support Dr Banda because, it was argued, he stood for discipline, unity and efficiency and was a “popular” leader. He was also a Kirk Elder and pro-West. The ills of his dictatorship, like intellectual repression, were often overlooked.

The fall of the Berlin Wall meant that the West no longer needed benevolent African dictators. The discourse became “aid for human rights”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

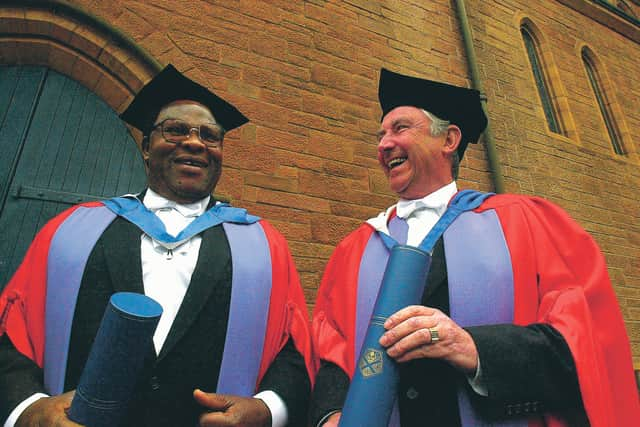

Hide AdThe introduction of multiparty democracy in Malawi in 1994 saw honourable and dishonourable politicians play the democracy game. President Bakili Muluzi handed out cash at public rallies – cash from public coffers, but Scotland still gave him an honorary doctorate in 1997, paving the way for the previously disciplined civil service and the police to be politicised. Elite impunity festered unabated with the state and its resources becoming anaemic “cash cows”, drained by ruling political parties for patronage.

Even then, Scottish institutions struggled to understand that the benevolent “elected dictatorship” had long been replaced by elites ruling in the president’s name, often without his knowledge. Unfortunately, Malawi’s development partners have proven to be adept at eagerly ticking off elections as “done”. In 1999, they concluded the elections were free and “substantially fair”, and the country moved on. This year, two weeks before the Constitutional Court judgement, an EU delegation went to Malawi apparently in an attempt to justify their findings of free and fair elections.

The “development mirage” in Malawi is that the existence of comparative freedoms suggests a working democracy at play. But impunity rules. Accountants Baker Tilly, for example, confirmed that at least US$32 million disappeared in six months from the national treasury under Joyce Banda’s presidency in a supposedly poor country.

All the while, ordinary Malawians have been watching, as powerless in many instances as they were under Dr Banda’s dictatorship. Where Dr Banda used force, “democrats” mostly use economic weapons against their enemies. Even so, in the 2011 anti-government demonstrations, 19 protesters were shot by the police.

The people are no longer having any of that. Gone are the days when people’s frustrations lay in expressions such as “What is the donor community’s view?” Tired of their right to elect being systematically “stolen”, the nation has rebelled. Fed up with being taken for a ride by an “elected” ruling elite and no longer counting on the intervention of development partners, demonstrations have ground down the already limping economy.

It is time for Scotland to join the people of Malawi and do away with its sentimental but clearly misplaced sense of history. Genuine friendship is based on hard truths and shared developmental aspirations for all its people, not just the elite who cling to power with impunity. Imagine the consequences for law and order if the court judgement were reversed.

Twenty-five years after Dr Banda left the electricity supplier Escom has not increased generating capacity much and blackouts occur daily, a testament to the milking of funds from parastatal organisations.

When the Scottish Malawi Partnership was established in 2005, some of us warned Scotland to avoid the mistake of falling in love with Malawi presidents and the ceremonial trappings of power. Clearly that lesson has not been taken on board.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Chipembere Lwanda, is the author of Kamuzu Banda of Malawi (1993 and 2009); Promises Power Politics and Poverty (1996) and Malawi: The State We Are In (2019).

George Lwanda, a strategist, is a 2018 Asia Global Fellow at Hong Kong University’s Asia Global Institute, an alumnus of the Mo Ibrahim-SOAS University of London Governance for Development in Africa Initiative and an alumnus of the TRALAC trade law programme