Lesley Riddoch: Working out the way ahead

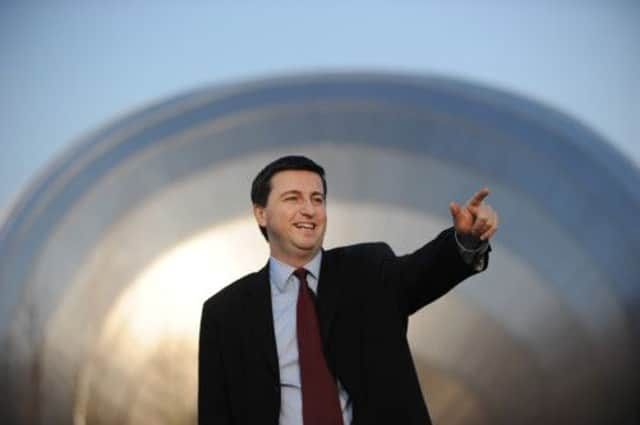

DOUGLAS Alexander has sketched out the shape of life in Scotland after a possible No vote in 2014.

It’s good to see positive arguments for the Union. But a case this sketchy which backed Scottish independence would simply be laughed out of town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Labour MP for Paisley and Renfrewshire South is of course right to say “Scotland good, UK bad” is simplistic, and right to question the wisdom of changing constitutional status just because the current UK government is unpopular in Scotland. As Alexander points out, “a 16-year-old voting for the first time will have had a UK Labour government for three-quarters of their life”. That’s far from reassuring.

The shadow foreign secretary seems to be admitting Labour is as much to blame as the Tories for the current debt-ridden, low-wage, trust-free, greed-led, judgmental, materialist mess that is modern Britain. I suppose he can argue Britain’s predicament is the result of temporary party political failings, not permanent structural problems. But it’s a very fine distinction.

In any case, Scottish political values have clearly diverged from rUK – an observation made repeatedly and without rancour at recent events organised by the Institute for Government in London, Workers Educational Association in Sheffield and BBC Radio 4’s Any Questions in Northumberland. In my experience, fair-minded English folk readily accept what Alexander cannot. Scots want to run their bit of the UK differently to other constituent nations of the UK. Few south of the Border deny that reality – they only debate how it might best be accommodated.

Alexander argues nationalists “rely on rekindling an outdated sense of victimhood” with the claim that Scots “never get the government we vote for”. It’s also hard fact. Since 1950 Scotland has voted Tory for six out of 63 years (9.5 per cent) but has had a Tory government at Westminster for 38 years (60 per cent). Put differently, just 1.7 per cent of Scottish MPs elected in 2010 were Conservative compared to 20 per cent of Welsh MPs and 56 per cent of English MPs. Those figures say something.

Not that “everyone south of the Tweed is an austerity-loving Tory”. But progressive forces in “the great cities of Liverpool, Newcastle and Manchester” are not actively interested in challenging the distribution of power and wealth in British society. They are not demanding regional assemblies to end their own complete dependence on a top-down, centralised system of governance. We know Scots aren’t the only members of Club UK. We just seem to be the only ones who want to rewrite the rules.

And there’s another practical reason Scots worry about “not getting the UK government they vote for”. A devolved government with limited tax-raising powers is dependent on the political priorities of Westminster for policy and spending on defence, Trident, benefits, welfare “reform”, austerity, economic strategy, international relations and war. Not small matters. Even devolved spending is a function of English spending patterns thanks to the Barnett Formula. So a persistent mismatch between voting intentions north and south of the Border within the Union necessarily hobbles democracy. Doesn’t that matter to unionists?

Alexander believes the socialist values of “struggle, solidarity and social justice” are the key to next year’s independence referendum. These are indeed cornerstones of Scottish society. But why? The UK is not apartheid-ravaged South Africa nor Communist-controlled Poland. So why is solidarity still vital for citizens with a GDP higher than Japan or Saudi Arabia? Why is struggle still necessary for old folk surviving a winter in the energy-rich UK? Why is social justice still a distant, glittering goal, not an everyday reality in a country governed by the so-called, “Mother of Parliaments”? In short, why is struggle still vital in Britain after 300 years of political union? Why after 40 years of oil and gas income has British society not been transformed? Why do parts of the UK now record worse health outcomes than eastern Europe? Nordic neighbours have achieved levels of social and political equality the British can still only dream about – how come?

One thing’s certain. The entire population of Scotland cannot stop each new southern captain from steering the great ship Britannia further away from the social democracies of Northern Europe towards a spot of splendid isolation in the mid-Atlantic. The Scottish tail cannot wag the British dog.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd what of Alexander’s post-referendum proposals – a Scottish National Convention in 2015 to discuss new powers and a decade dedicated to matching Finland’s world-leading school results.

Another decade discussing the constitution would be fairly unthinkable. And the Labour-devised/SNP-delivered Scottish Curriculum for Excellence is already modelled on Finland’s world-beating educational system. The English educational system on the other hand – with privatised academies, relentless testing and league tables – is as far from the equality-focused Nordic model as it’s possible to get.

Finally, Alexander attacks those who disparage 300 years of union which have produced “world-class writers (such) as Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott, nurtured leading scientists like Alexander Fleming, John Logie Baird and Sir John Clerk Maxwell and reared outstanding athletes such as Kenny Dalglish and Sir Chris Hoy”.

One could argue that such talented individuals would have excelled inside or outside the Union. But Alexander’s emphasis on elite performance reveals a deeper problem with Britishness. Dutch psychologist Geert Hofstede compared societies in the 1970s and classified Britain as a masculine society driven by competition and achievement where success is measured by the performance of a small elite of winners.

Sweden (and all the Nordic nations) were classified as feminine societies which care for others, achieve a high quality of life for all, tend towards conformity and attach importance to the performance of the average, not the elite. There are of course shortcomings in both models. But Alex Salmond and Douglas Alexander both aim for high Nordic standards of education, equality and well-being.

That simply can’t be done by focusing on the success of elite performers alone.

Transformational Finnish-style results happen when professionals change their lives to ensure every child matters – not just the high flyers. Is such change ever likely to happen within the elitist, privatising, competitive UK?

It’s not just born-again nationalists who need more detailed evidence than Alexander has presented.