Leaders comment: SNP slipped up on North Sea oil

The slogan “It’s Scotland’s Oil” fuelled the rise of the Scottish National Party through the subsequent decade and has been a constant in the national conversation since. But few could have predicted the role it is playing in the independence referendum campaign with less than a month to polling day.

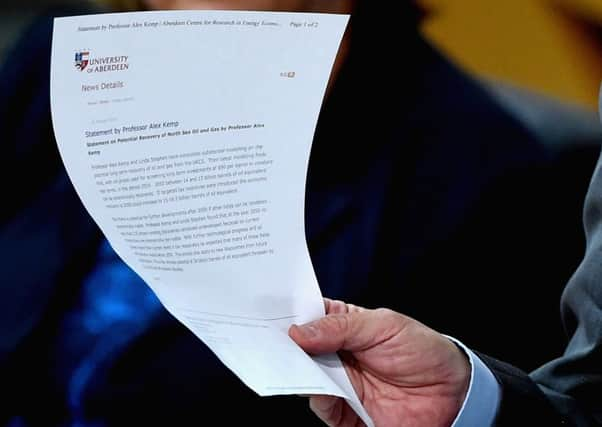

The disagreement between the Scottish Government and tycoon Sir Ian Wood – the pre-eminent Scottish oil industry figure, by some margin – has raised an unexpected question mark over what should have been one of the Yes campaign’s most bankable political assets. The SNP has landed itself in this predicament through a miscalculation that can be seen throughout its White Paper. At all points and in all circumstances – through currency plans, economic projections and scenarios for membership of international organisations – it has consistently used best-case scenarios rather than more measured, cautious and realistic criteria. While its desire to present a rosy picture of independence is understandable, this has tested some voters’ credulity. An example of this is the way the SNP bases its calculations on the amount of oil thought to be left in the North Sea, rather than the amount that can physically be extracted with current technology.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe history of how the UK has used the natural windfall of North Sea oil and gas does not reflect well on Westminster rule. The infamous 1974 McCrone report on the new bounty was suppressed, presumably to avoid Scots voters getting a true picture of its potential to support an independent state.

There was no attempt to build up an oil fund for future generations, as the Norwegians did with great foresight and wisdom. Instead, successive Westminster governments used oil revenue for their own immediate political priorities. Sometimes these were contrary to Scottish political instincts – such as Margaret Thatcher’s tax cuts for the rich – and sometimes they were in tune with Scottish priorities – such as Tony Blair pumping billions into the NHS and other frontline public services. But there was little longtermism.

One of the arguments frequently used by Yes campaigners goes something like: “Scotland is the only country in the world to have discovered oil and gotten poorer”. This is nonsense. Scotland now is a much more prosperous country than it was in the 1970s, with a higher standard of living, better housing, better health, less poverty, more enterprise, a better-educated workforce and a far greater sense of self-confidence and self-sufficiency. Little of these advancements can be said to have stemmed directly from the benefits of discovering oil in Scottish waters, however.

In the current referendum debate, oil has not played as great a part as some might have imagined. Yes strategists have instead emphasised their belief that Scotland can hold its own as an economy even when oil and gas revenue is separated out. SNP politicians have preferred to portray North Sea revenue as an added bonus, not as something on which an independent Scotland would rely. With North Sea oil due to run out at around the time Scotland’s youngest voters are sending their children to university, this is perhaps wise. Although the part played by oil in the current campaign is different from the past – it is now wrapped up in the currency debate as a demonstration of how a Scottish economy might differ structurally from the rUK economy, and therefore potentially test a currency union – its role as an underpinning of the independence argument remains. And despite its much-discussed volatility, it is an undoubtedly a strong pillar of Yes case. Which is why the SNP’s spat with Sir Ian Wood is the last thing it needs.

Let’s bring MacDonald in from the cold

WHEN you type someone’s name into Google, the search window will suggest other words often associated with that person in other searches. When you enter the words “Ramsay MacDonald”, the word that immediately comes up as a suggested search term is “traitor”.

There is no more controversial political figure in Scottish political history over the past century. On the face of it, James Ramsay MacDonald should be a celebrated figure – the Scot who was one of the founding fathers of the Labour party, who in 1924 became the first ever Labour prime minister.

And yet his subsequent decision in 1931, two years into another Labour administration, to form a government of national unity with the Conservatives and the Liberals was seen by most of the Labour movement as nothing short of a betrayal. He was stripped of his Labour party membership, and he was never forgiven. When he died in 1937 he went largely unmourned by the party he helped to create, and which he first brought to power.

Relatives of MacDonald in his native Moray have decided to open his family home to the public to give them an insight into the life of this landmark figure in Scottish history. And perhaps it is time for a reassessment of MacDonald and a reclaiming of him from the infamy of the past three-quarters of a century. His decision to enter National government was prompted by the catastrophe of the great depression, a seismic event on a scale we can only imagine today (our own recent economic crisis pales in comparison to the social impact felt by ordinary families in the 1930s). MacDonald was never forgiven for abandoning socialist orthodoxy and instead backing the Gold Standard that kept prices high, and siding with the more conservative elements in society, including the bankers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut more recently, some economists and historians have begun to look more kindly upon him. They say his economic strategy in the face of a national – and international – catastrophe may well have been correct, and that MacDonald’s approach foretold the later accommodation of the Left with the market that saw social democratic leaders come to power across the western world in the late 20th century. MacDonald may have his moment yet.