Kirsty Gunn: We may be proud Scots but that does not mean we really want to rise up

Only, there at the beginning of the recording is something listed as “artist’s own”, a rousing call to the nation to “rise up like an eagle” and be great again.

“What’s that all about?” I’d said to Maureen when we first sat down to listen together and she wanted to play the whole recording through, from start to finish. “That doesn’t sound too traditional to me.” I said. “It sounds like something that might have been composed for the 2014 referendum.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

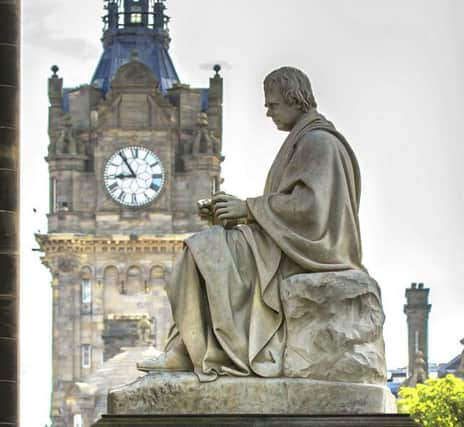

Hide AdWe played the song again. “Well, I didn’t notice that, but I see what you mean,” she said. “That’s not ‘Rowan Tree’, is it? And I certainly do NOT want to rise up like an eagle, or anything of that sort” - at which point our conversation turned to the amount of self-referencing that is going on all over the place these days, from the Walter Scott quotes about what it is to be Scottish and in Scotland all over Waverley station and similar in the airports, to having “Scottish Produce” stickers on the meat and veg in the supermarket.

It’s political, of course, and always has been – this creation of a “Scotland” in order to shore up national feeling and get the results politicians want, for whatever party, at whatever time in our history. But the fact is, our history, bar the odd bit of invention by Walter Scott, who swathed all of Scotland in the same tartan, as it were, much in the same way Nicola Sturgeon would have us swathed now, is one of a nation of parts, different sensibilities for different regions, bound together by a history that is dignified and set apart from the rest of the British Isles by a distinctive literary and musical tradition. And we know all about how wonderful that is, that tradition, the poetry and the piobaireachd and, more recently, over the last few hundred years, the novels and kinds of fiction we write that’s always been so ahead-of-the-game, artistically speaking. We don’t need a CD to feature words from the Border Ballads to remind us of that.

So why all the talk of “Scottishness”, indeed, as Maureen pointed out? It’s exhausting. “And infantalising, actually,” we concluded, as we turned off the young man’s lovely voice with a resolved “click”. “No-one with any sense wants to rise up,” we said. Because everyone knows rising up isn’t like being an eagle at all. It’s having a war or a revolution. “And both,” as Maureen concluded – while still owning that “that young tenor has a lovely voice and I think I am a bit in love with him, I am!” – “are time-wasting and expensive.”

Her sister-in-law, Una, who sent the CD, likes the young man too. “He’s just gorgeous,” she said to me on the phone, when she was calling to arrange a visit to my mother-in-law. She comes over to Edinburgh from Fife every couple of months and the two of them go out to a film or a play together. Maureen was born and spent her early years in Fife but considers herself a native of Edinburgh “through and through”. Still, she likes to get across to Fife to see her brother and his family, and her sister-in-law; and when our children were small, they and their cousins used to have part of their summer holidays there too.

So Fife, Edinburgh ... these distinctions course clearly through my mother-in-law’s mind when large-scale claims of nationhood are made. Whether it’s “The Kingdom of Fife” or “The Capital”... Clearly she’s not the only one: we’ve always liked differentiating things. Allowing for differentiation allows for ways of being together, is my view – and it’s one that might hold not only for Scotland, but for the whole of the UK, and for that matter, the world.

A great friend of my husband, the artist Graham Johnson, had a succinct and compelling letter in The New Statesman recently calling for a “fully federal” UK. “Only then can the Westminster hegemony and its disfiguring gravitational pull be tamed and tensions dividing the UK eased,” he wrote. He’s not the first to draw our minds in that direction, of course. There’s been growing discussion around the concept of a devolved power spread across the nation that might give increased powers to those whose only voice could be expressed by a cry to “Leave” last summer, and shout “Yes” before that. But I wonder, too, about a more federal version of Scotland, as well?

Certainly Holyrood could do with a similar spreading of influence, and avoid following the same pattern, by tending only to its own central belt constituency, as has been set down south with its focus there rather than towards Northern and Eastern regions. We don’t want to make the same mistake, do we? Yet increasing centralisation suggests that we already are.

Allowing for all of our different ways of doing things across the land eases tension, dissolves nationalism, and makes friends with other ways of thinking. Instead of trying to overwhelm differences, and pretend they don’t exist or have been subsumed by the dominant culture such as the term ‘multi-culuralism” suggests, we might have more of an exchange between all engaged parties. Certainly my own Caithness family are not one whit like my dear mother-in law’s’ “Sassenach lot” as my father refers to them, affectionately of course. The term “inter-cultural” is useful as anything in these kinds of moments, I find, for “inter cultural” lets difference in, and makes it into a discussion. It’s friendly and interesting and engaged – it describes my father’s love for my Edinburgh husband and his family, if he can call them a bunch of Sassenachs. For that matter it describes my mother-in-law’s love for that revolutionary young SNP-leaning tenor of hers, too.