Kirsty Gunn: A best-selling author, now out of fashion

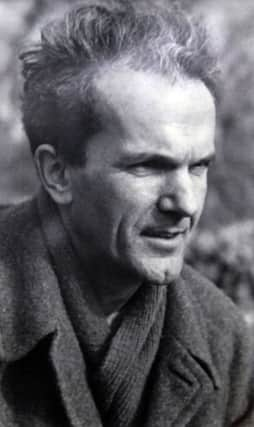

I write this week from The Dunbeath Heritage Centre in Caithness. I knew it for years – and still think of it, actually – as The Neil Gunn Centre, a museum situated in what was once the Dunbeath School at which the writer, a distant relative of mine, born in 1891, was a pupil until 1903. I say “the writer”, but what I should be able to say is “one of Scotland’s most important writers”, and “one of Britain’s foremost modernists” – but am prevented to because of the terrible way Gunn’s reputation has fallen out of fashion, so it seems.

In his lifetime, he was, by today’s standards, a best-selling author, widely published, broadcast and filmed at all phases of his literary career. His most well-known novel, The Silver Darlings, was an international sensation, and continues to be reprinted by Gunn’s original publishers, Faber and Faber, every few years, appearing with a bright new cover and introduction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHow can it be? That a writer whose work is as fresh and original now as when it was first written is so neglected? His name does not appear in university reading lists; his work is not anthologised or the subject for widescale critical debate around Scottish and British post-war literature.

We continue to talk about the impact and effect of Lewis Grassic Gibbon and George MacKay Brown, along with the poets of the period as well, of course, MacDiarmid and MacCaig and Muir and the rest… We know how important these voices are in describing a Scottish canon, giving us increased understanding of ourselves as a culture.

But apart from a small circle of scholars and enthusiasts continuing to publish articles in specialist journals that might remind us, there is absent from the roll-call a name that singlehandedly in his own lifetime put a small corner of a particular county of Scotland on the map. For a while, Caithness was as known to readers as any setting for a novel anywhere, and the writer’s world – mysterious and quotidian, both – was understood by all kinds of readers, not just the fancy literary kind.

It’s off the beaten track, of course, Caithness – despite the success of the North Coast 500, the newly celebrated tourist road that might connect the Highlands of Scotland from Inverness and back again, bringing visitors to the region who might have otherwise missed out this part of the North.

“After all, we’re not the West Coast” as they say up here. “Caithness is… Caithness.”

It’s a part of Scotland that’s always sat to one side of the rest of the country, feudal and private, not nearly as affected as the rest of the Highlands by the so-called “land improvements” and industrial change; divided always from the rest of the country by the dramatic Ord that for years inhibited travel from the south, and out of the way, generally, by dint of sheer distance.

It’s the West, we all know, that gets the attention – “wild land” designation and funding and all the rest – and the national parks and tourist go-to zones like Loch Ness… Caithness simply doesn’t figure in the same way.

Except… There is Neil Gunn.

This past autumn at Dundee I delivered the inaugural Neil Gunn Lecture as part of our first year studies, drawing upon the inspiration of Highland River and suggesting that the novel should take its place in the canon of High Modernist literature, along with the likes of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Katherine Mansfield’s Prelude and DH Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI encouraged my students to think of Gunn’s story less as fiction in the traditional sense – a story that is made up to be about something – than what I called a “Creative WorkBook”.

Yes, it’s a story, a wonderful one, I said, but it is also, significantly and originally, an example of nature writing, memoir, biography, history, a how-to manual for budding fishermen, and a reflective essay about the making of literature itself.

The whole thing a record of its own ideas.

My hope was to light a spark.

Would that it might lead to further projects – be the stuff of a Creative Scotland grant, say, or a university PhD scholarship award, or a sparkling new literary fund. But Neil Gunn is not fashionable or, to use Creative Scotland’s phrase, “relevant” enough for that. Gunn’s writing, to a lesser or greater extent in all his novels, is deeply idiosyncratic; he was a nationalist in the sense that he loved his country, not that he followed some party line or other. More than anything, he was concerned with the relationship between the teller and the tale.

It’s that feature that puts him in the Modernist camp – and, along with his interest in Eastern philosophy and Buddhism – may be why he’s come to be ignored in contemporary literary studies and mainstream reading. We have a suspicion of “art” in Britain, and, in Scotland in particular, have always valued common sense and the bright white of the enlightenment over mystical hippyish ideas of zen and orientalism.

Following the lecture, my colleague, Dr Lindsay Macgregor, directed a writing and performance workshop that drew upon images of the Dunbeath river and its environs – images on loan from the Heritage Centre, in fact – some of them decorate the walls of the museum below the Neil Gunn Research Room where I now write.

It’s a stormy bright early spring day here in Caithness, the wind at work upon the surface of the North Sea, roughing it up with whitecaps and streaking the dark channels with a dark and violent looking blue. The green spears of daffodils are coming up through the grass, defiant looking and all the more lovely for it.

The river, the Dunbeath river that was the source of so much of Neil Gunn’s creative output runs cold and fast down towards the harbour, overlooked by a little terrace of houses, one of which sports the blue plaque: Neil Gunn, writer, was born here.

We’d do well to remember our far away places, and ignored writers, in our consideration of what Scotland means today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new, the fashionable, the talked about – whether it’s the North Coast 500 or Irvine Welsh’s latest little earner, Trainspotting 2, or a politically “relevant” arts project that shouts Scotland Today! These are all one way of depicting ourselves to the world. But there’s more to us than tourism and sensationalism and one-party politics. We might also pay more attention to that which has been forgotten in our past and present too.