Joyce McMillan: Labour could push Scots to Yes vote

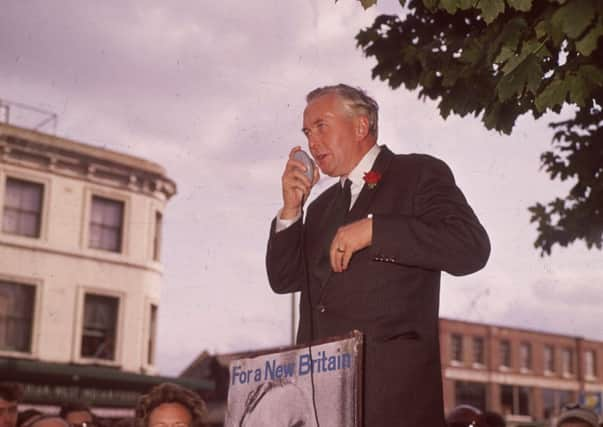

AT THE time of the general election of 1964 I was 12 years old, and already showing an interest in politics that bordered on the avid. I remember going with my father to a Labour Party rally in Johnstone town square, where we saw our Labour candidate Norman Buchan deliver a rousing speech to the crowd, alongside a flame-haired Barbara Castle.

The atmosphere seemed electric and as it turned out, Norman Buchan’s victory in that election – over the sitting Tory MP for West Renfrewshire, John McLay – was unusually significant. Harold Wilson became Labour’s first prime minister since Clement Attlee, with a majority of just four seats and the rest, as they say, is history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne thing I do clearly remember about that election was that John McLay’s posters described him not as a Conservative, but as the “Unionist” candidate, while Norman Buchan, by contrast, belonged to a radical tradition of Clydeside Labourism that held no brief for the British constitution, and saw no need to defend it.

As any shrewd historian of British politics is bound to note, one of the most striking shifts in Scottish politics over the last half-century involves the almost exact reversal of those roles. The Westminster Conservatives now have so little presence in Scotland that they have almost ceased to think or feel like an effective UK-wide party.

And Labour, by default, has become the dominant party of the Union; so much so that last weekend’s fascinating Scotsman ICM poll, which showed the Yes and No camps in the independence referendum running almost neck and neck, found that a probable Labour victory in next year’s UK general election could add a crucial two percentage points to the No vote, and knock three points off the Yes vote.

So what are we to learn from this gradual but apparently inexorable turn of events? In Westminster circles, there is a certain tendency to dismiss Scotland’s apparent preference for Labour governments at Westminster as some kind of knee-jerk tribal response to “Tory toffs”.

In truth, though, the reasons behind the shift in Scottish politics are far more profound, and Westminster’s deafness to those reasons is a problem that will continue to haunt UK politics, regardless of the outcome of the Scottish referendum.

In the first place, most Scots disliked Margaret Thatcher not because of her class or gender, but because of her rigidly monetarist and individualistic ideology, which never won majority support in the UK as a whole, and was even less popular, for obvious social and industrial reasons, in Scotland.

Over two decades, the Conservatives’ embrace of neoliberal ideology gradually reduced it to a minor force in Scottish politics, with just one Westminster MP out of 59. And while it is absolutely foolish to talk of an independent Scotland as a probable Tory-free zone – there are plenty of conservatives in Scotland – it is true that in order to flourish, any post-independence Scottish Conservative Party would have to return to a more pragmatic and genuinely business-friendly style of centre-right politics, and distance themselves from the UK Tory party’s long and wasteful ideological war against the very idea of the state.

The problem for the Union, though, is that if neoliberalism has turned the Tories into a liability when it comes to the defence of the UK, it has also had a corrosive effect on the Labour Party, and on its ability to stand up for the values of solidarity and social justice that gave the Union a new meaning and legitimacy in the post-war period.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn Wednesday, The Scotsman published a thoughtful and touching essay by Labour’s shadow foreign secretary Douglas Alexander about his feelings for Scotland, and his conviction that we can best express our commitment to positive values of social justice and equality by remaining bound together with our fellow citizens in the rest of UK.

This is, I think, about as good as it gets when it comes to an attractive and positive Labour perspective on the present debate. Yet what is missing from it is an understanding of how Westminster itself has changed over the last generation, and how similar the Labour and Conservative parties at Westminster now look to Scottish voters 400 miles away.

And it’s not only that the social composition, the voices, the dress, the carefully standardised appearance of politicians of all parties has become more similar – it’s that Labour’s quiescence in huge rafts of right-wing and neoliberal policy, from the deregulation of the banks, through privatising “reforms” of public services, to the recent shameful collusion with Tory gesture politics on immigration and benefits, has convinced growing numbers of Scottish voters that a change of government at Westminster is no longer enough, and that there is a better chance of defending basic social-democratic values in an independent Scotland.

Now, of course, this argument is not over. As the ICM poll shows, there is still a significant body of swing voters who would give the Union another chance if they thought Labour would be in government. And as Nicola Sturgeon observed in her SNP conference speech, there are still legions of Scots who “have Labour in their hearts,” particularly when it comes to a Westminster election.

What Labour seems to struggle to grasp, though, is that the SNP would not now be in its current strong position in Scottish politics, and the polls on independence would not be be narrowing as they are, if so many Scots had not begun to feel that they could no longer trust Labour to defend those social values that lie closest to their hearts.

It seeems that for most Scots born since 1945, Britain is the land of the welfare state, the land of social justice, a land of equal opportunity and declining inherited privilege, or it is nothing. And if we end up voting Yes in September, it will be because the old party of Union foolishly set out to reverse that popular post-war settlement. And because the new party of Union, the Labour Party, proved to be a feeble defender of it, half-seduced by the ideology of its enemies, and therefore confused, apologetic, and uncertain of touch, just at the moment when it needed to be precise, quick-witted, inventive, and unambigously proud.