John McTernan: Passion needed in modern government

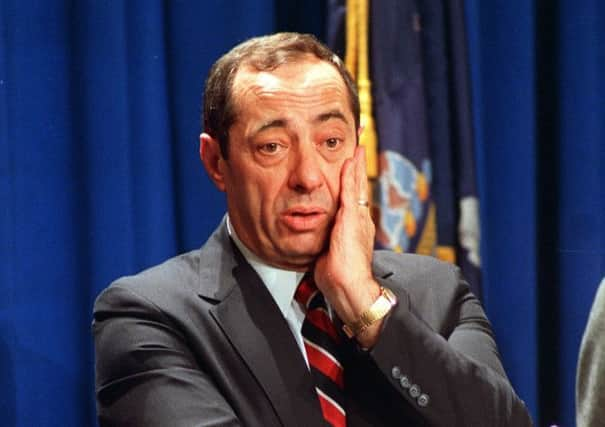

‘You campaign in poetry. You govern in prose’ was Mario Cuomo’s famous saying. A thoughtful and literate man, he was himself known as Hamlet on the Hudson for prevaricating about running for the Democrat nomination for president while he was Governor of New York. It’s a brilliant phrase and often quoted to explain the gap between the inspirational rhetoric of political campaigns and the mundane reality of wrestling with the complexities of government.

Yet more and more this year it has seemed that Cuomo was wrong. The revolt against traditional politics over the last few years has in many ways been a revolt against the prosaic nature of modern government and the leaden political discourse that surrounds it. That unappetising mixture of boiler-plate prose, jargon and lazy clichés – hard on the eye, worse on the ear. The truth is politicians need to govern in poetry.

CONNECT WITH THE SCOTSMAN

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• Subscribe to our daily newsletter (requires registration) and get the latest news, sport and business headlines delivered to your inbox every morning

A better quote for modern politicians is from Yeats, not the oft-quoted “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold” but rather “Tread softly because you tread on my dreams”. That’s the big divide in modern British politics – the battle between the dreamers and the realists, the fight between those who ask “Why can’t it be like this? Why not?” and those who patiently and pedantically explain exactly why not. That was the argument between Yes and No in the referendum and is the one between Ukip on the right and the Greens on the left and the mainstream parties.

At the close of the year there is great disagreement at the heart of politics but a strong sense of people talking past each other – there is no shared ground for debate. As Dr Johnson apocryphally said of two shopkeepers arguing with each other: “they will never agree, because they are arguing on different premises.” As the polls show, this only benefits the fringe parties – though for how long can that be maintained as a description when they command the support of a third of all voters with the remaining two-thirds divided between the Tories and Labour.

Something’s got to give. And if it’s not the mainstream parties then it will be the whole system. Between passion and logic chopping the voters increasingly choose the former. They go for politicians who promise, to adapt the words of George Wallace, poetry today, poetry tomorrow, poetry forever. Or more mundanely, ones who simply say that things can be so much better – all you have to do is to break the current system whether it is the UK (the SNP), the EU (Ukip) or capitalism (the Greens). So the mainstream parties have to change to meet the challenge. Just the facts are no longer enough. Look at the difference that Gordon Brown made to Better Together’s campaign when he joined it. He brought soul, passion, values and belief. He brought poetry. But why did it take so long for the No campaign to find this voice?

To go back to the political discourse – it is so economistic, so driven by facts and figures. Now the economy is important; without wealth being created there would be no wealth to redistribute. But, as any economist would tell you, economics isn’t everything. We need well-being as well as wealth, we need to create that and, as David Cameron used to say in opposition, find a way to measure it and its growth. For it is a truism that what gets measured gets done. But there is a reason that economics dominates political discourse and it is not simply the demands of the modern media nor the so called “neo-liberal consensus” (which is in reality an old-fashioned social democratic acceptance of what used to be called a mixed economy.) It is the way so many of our leading politicians are educated, with the gold standard being PPE (Politics, Philosophy and Economics.) So not only is the soul ground out of them at an early age it is done at the same time as they are taught there is no such thing as a soul. The result is a world where it is of note that one Cabinet minister, Michael Gove, reads and indeed tries to read about 30 books a year. A world in which one leading Labour figure saw that I was reading a volume of Seamus Heaney and said: “Poetry? Very much the intellectual!”

Imagine if our politicians actually read books, not press summaries. One of the best analyses of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First century is that it is like reading Balzac. Would that MPs read Piketty, let alone Balzac. The most sought-after item in Westminster this autumn was the seven-page summary of Piketty prepared for President Obama by the chair of his Council of Economic Advisers. But imagine if they routinely read poetry. How much more interesting their speeches and documents would be? Out with cliché, in with thoughts crisply expressed – in the words of Pope, politics too would be a matter of “What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d”. Would politics be more listened to and politicians more respected if they were witty? The answer may be in the popularity of Alex Salmond, Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson. Not just figures who seem attractive to the public, but whose free-thinking is thought to be mirrored in their fresh language.

What if they had studied English literature rather than PPE? More members of the first parliamentary Labour Party had read John Ruskin’s Unto this Last than had read Marx. Arguably this was much better intellectual fuel for them since within less than 20 years they had supplanted the Liberals and become a party of government. I’d make Ruskin compulsory reading for all new Labour MPs.

But the prize is poetry. Wouldn’t it be great if politicians knew more poetry than the quotes that their researchers Google or find in a book of quotations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd given how far from poetry they mostly live total immersion is required. So, A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, Paradise Lost, The Cantos, The Iliad – anything you can lose yourself in.

To govern in poetry you first have to think in poetry.

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND IPHONE APPS