John Campbell: Let’s hear it for our languages

One of the most difficult things to understand about public life in this country is the way in which speakers of two of our native languages, Gaelic and Scots, are so often subjected to unreasoned attacks in the media.

While some sort of critical debate on government handling of our endangered languages might have been hoped for by now, this hasn’t happened. Instead, detractors typically affect a peculiar pride in not understanding anything other than English, which ability they brandish as a cudgel against anybody daring enough to speak something else.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese attacks show a remarkable similarity in content and structure. They have a manufactured feel, as if they originate in some writers warehouse. Left-wing, right-wing, Yes vote, No vote, they all peddle the impression that, whatever sort of country emerges after next year’s referendum, linguistic diversity should not be part of the landscape.

That is regrettable but possibly understandable given that most people’s experience of language planning has been negative.

Subtractive language planning designed to replace Gaelic and Scots with English was initiated by Scottish authorities more than 400 years ago and was the default position in church and state until very recently.

Contemporary language planning is positive. Its purpose is to equip people with languages in addition to English, not instead of it, thus enabling some of us to become bilingual.

That in itself presents a professional challenge to which some educators and journalists have been unable or unwilling to respond.

The lack of veracity in many typical attacks on bilingualism is easy enough to counter. The emotional impact is another matter. In his witness statement to the Leveson Inquiry into press ethics, the demographics expert and veteran media commentator Professor Kenneth MacKinnon describes in detail how attacks on Gaelic are often motivated by fear of other minorities and their languages. He calls this “Linguaphobic Syndrome by Proxy”.

When minorities are singled out for attack the effect is sickening. To know that others rejoice in the possibility of our demise is disturbing.

I first encountered linguaphobia was 50 years ago as an eight-year-old in a Lanarkshire primary school. The first time I saw a tawse being used was on my own hands. The punishment for answering a trick question with “Aye” instead of “Yes”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe teacher asked us all in a friendly tone if we liked toffee and noted the response. Those who said “Yes” were rewarded with a sweetie. The boys who said “Aye” got the belt. The girls were given lines: “I must talk properly in class.”

This was Scottish education. The best in the world, it was said. Through the Cold War period teachers often told us that we enjoyed “education, not indoctrination”.

Fortunately, I had some real education at home. My grandmother came to stay with us. Her language was Highland English, full of Gaelic and Scots words and phrases. “Dèan suidhe air do thón ‘s bi samhach an A’ll read ye a story”, she would say. “Sit on your behind and be quiet and I’ll read you a story.”

The story was often from one of her most treasured possessions, now mine, a New Testament in Braid Scots. An almost heretical document, its language is friendly and familiar while the King James, authorised version, seems cold and joyless.

In Scots, Jesus, the Maister, sits doun by the Loch o Galilee. If Scots is good enough for Jesus, I reasoned, then it must be good enough for me. So I did what I could to learn Scots and Gaelic too. I can’t claim to be very good at speaking either of them but both have enriched my life.

I have travelled in my own country, not only physically, but culturally and emotionally. Speaking to people in different places in Gaelic and Scots is a joy that has to be experienced to be understood.

I have heard tales of Ossian and Finn MacCoul and learned how to build a bow tent from Gaelic-speaking travellers. I have learned about farm work, “frae yowkin time tae lousin time” and been shown how to repair nets and set sails, all in Scots.

That I will never be a farmer or a fisher doesn’t matter. Language is creative and Gaelic and Scots are liberating. Its structure, vocabulary and concepts can be applied in new situations I encounter.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe sounds that our teachers despised and did their best to belt out of us are sounds that have helped me to learn other languages too and to judge for myself some of the accepted truths of the Anglosphere. For example, that nobody else can make good television.

Having discovered the wonders of Flemish television, which I can follow without subtitles, I now rarely watch English language programmes. I hope to learn French in the same way, by watching television.

I gave up French early in school, having been told that my accent was some sort of handicap. All these years later, as I look forward to my bus-pass, I understand the destructive effect of that lie and I wonder how many others must have been similarly discouraged.

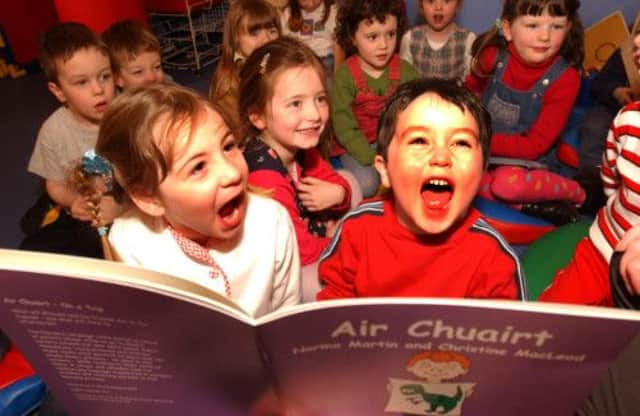

Now we are entering a more enlightened age when old hostilities are being set aside. Young people are encouraged to love and to enjoy using their languages, the better to understand the world and to share in its riches. The sounds of Gaelic and Scots are the keys to the world.

• John Campbell is a freelance writer and researcher, and is a regular contributor to The Scotsman’s Gaelic page